Inhuman and Degrading ‘Hotspots’ at the EU Borders

An Analysis of How the ECtHR Rejects the Attempt to Push Asylum Seekers Into De Facto Legal Vacuums at the Borders of the EU

On 4 April 2023, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) published its judgment A.D. v. Greece, for the first time condemning the living conditions in the so-called ‘Hotspots’ on the Greek Aegean Islands. The applicant, a pregnant asylum-seeking woman, stayed at the Samos Reception and Identification Centre (RIC) for 2,5 months in 2019 until she gave birth. In its judgment, the Court provides an insight into the inhuman conditions in the Samos ’Hotspot’ and acknowledges the lack of access to legal protection for asylum seekers in Greece. In this article, we analyse the judgments’ novel aspects against the legal backdrop of the Court‘s jurisprudence and the political context of the EU hotspot approach. We argue that the Court finds and condemns the creation of de facto legal vacuums in the ‘Hotspots’ at Europe’s external borders.

The Circumstances of the Case

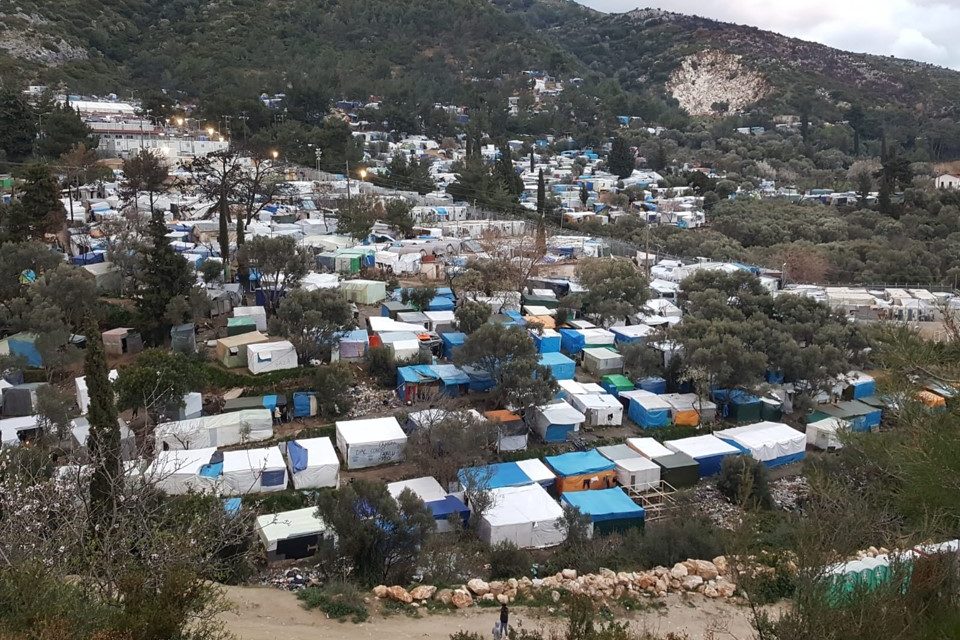

At the time of her arrival, the applicant was 6 months pregnant and had already suffered several miscarriages. However, the Greek authorities in charge of the massively overcrowded Samos ‘Hotspot’ that had a capacity of 648 beds but hosted 4190 persons at the time, did not provide her with housing but subjected her to a geographical restriction that prohibited her to leave the island and left her to fend for herself. A.D. was forced to live in a tent in the informal ‘jungle’ surroundings of the RIC without access to sanitary facilities. Later, after her tent had been destroyed by a fire that broke out in the camp, she lived in a tent within the RIC. More than 100 persons had to share one toilet, the sanitary facilities were in a precarious hygienic condition. In addition, A.D. was barely able to access prenatal health care before being admitted to the hospital where she gave birth to her daughter (cf. paras. 1-9 of the judgment).

The Court Dismisses Greece’s Attempts to Evade Their State Responsibility

The Court’s unanimously adopted judgment is rather short but pleasantly clear and finds a violation of the prohibition of torture or inhuman or degrading treatment from Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

In their written observations, the Greek Government focused on legal arguments essentially aiming to relativise the State’s absolute obligations under Article 3 ECHR. In particular, the Government, like in many asylum-related cases since 2007, claimed that Greece had been confronted with a “new migration crisis” which had been an “exceptional situation” that made it impossible to provide adequate reception standards. Additionally, it asserted that the living conditions in the overcrowded hotspots were the result of the closed borders of other European States and their “reluctance” to receive a proportionate number of asylum seekers. Further, the Government tried to build an analogy to the case of N.D. and N.T. v. Spain, claiming that the applicants were partly responsible for their ill-treatment since they had “deliberately” approached the Greek islands in spite of a “safer and less risky and arduous manner to apply for asylum” they could have allegedly chosen.

It is the shortness of the Court’s reasoning that shows how unpersuasive these arguments are. The Court simply repeats what it had already established in M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece: While it notes “that the States which form the external borders of the European Union are experiencing considerable difficulties in coping with the increasing influx of migrants and asylum-seekers” (para. 29), it clearly states that “having regard to the absolute character of the rights secured by Article 3, that cannot absolve a State of its obligations under that provision” (para. 30).

The dangerous attempts of the Government to evade their individual and absolute responsibility to comply with Article 3 ECHR are not even mentioned by the Court.

The Threshold of Severity

Having stressed the absolute character of Article 3 ECHR, the Court elaborates on the required threshold of severity and its case-law establishing general principles concerning the living conditions of asylum seekers. The Court refers to the cases of Mahmundi and Others v. Greece (para. 70) and R.R. and Others v. Hungary (para. 64) as summaries of “general principles concerning the living conditions in respect of pregnant women and the duration of ill-treatment” (para 33). It is remarkable that the cited sections do not include an abstract summary of principles but rather individual case assessments on the threshold of severity taking into account the particular circumstances of pregnant applicants. It seems that the general principle that the Court refers to is that the specific circumstances of pregnant women are considered by lowering the necessary threshold of severity to a reduced minimum duration of ill-treatment.

In A.D. v. Greece, the aspect of the required duration of ill-treatment had also been stressed by the Greek Government. The respondent tried to compare the case of A.D. to the case of B.G. et autres c. France, which involved minor children and their families, by framing the 2.5 months that A.D. had to spend in the Samos RIC as a “relatively short time” not exceeding the threshold of severity.

A Brief Reasoning That Leaves Uncertainty

The Court not only refrains from recalling its general principles on living conditions for asylum seekers but also provides a rather brief application of the general principles. In its assessment of the circumstances of the case, the Court mainly relies on the reports of the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights – that had described the Samos RIC as a ‘struggle for survival’ – the Greek National Commission for Human Rights and the observations submitted by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees that had intervened as a third-party intervener (para. 35). Apart from that, the Court only observes that ‘the applicant was in an advanced stage of her pregnancy and therefore in need of specialised care’ (para. 34) and based on this finds that the threshold of severity for a violation of Article 3 of the Convention was exceeded (para. 36).

By this, it remains unclear which importance the pregnancy and resulting vulnerability of A.D. had for the Court’s finding. On the one hand, the brief elaboration of the applicant’s individual situation and the importance of the reports on the general situation in the Samos RIC for the Court’s assessment, suggest that the living conditions in Samos were not compatible with Article 3 ECHR for all residents, irrespective of specific vulnerabilities. On the other hand, the Court’s referral to general principles in respect of pregnant women and to the applicant’s need of specialised care can also be understood as a vulnerability-based-approach. More clarity might be provided in the course of other pending cases concerning the ‘Hotspot’ Samos (e.g. D.F. and others v. Greece; A.R. et autres c. Grèce).

A reason for the briefness of the Court’s reasoning, and one of the major differences to the case of B.G. et autres c. France, might be the overwhelming documentation of the living conditions, both publicly available and individually provided by the applicant. In B.G. et autres c. France, the Court based its assessment of the conditions in a provisional camp in France, inter alia, explicitly on a lack of precise evidence of the living conditions in the reception facility and the applicants’ individual situation in particular (para. 89).

No Access to Legal Protection in Greece?

Another relevant outcome of the case is the Court’s view on the non-exhaustion of domestic remedies. The applicant had not submitted any written requests to the competent authorities or domestic courts. Instead, she directly applied to the ECtHR. However, the Court reiterated that the “rule of exhaustion of domestic remedies must be applied with some degree of flexibility and without excessive formalism” (para. 24) and followed the applicant’s submission that any existing remedy was just theoretical and factually not accessible or effective: “Having regard to the facts that no relevant case-law has been provided by the Government and that the applicant’s accommodation needs were known to the authorities from 16 August 2019, but were not addressed until 11 November 2019” (para. 25), it dismisses the Government’s objection.

The combination of the Court’s assessment that there were no effective remedies for the applicant and the heavy reliance on the reports and third-party-observations on the general situation in Samos acknowledges the structural dimension of the ill-treatment of migrants in the hotspots: The Samos RIC – and all four ‘Hotspots’ on the Greek Aegean Islands – must be viewed as facilities where the most basic human rights guarantees were violated in thousands of cases day by day while there was no access to legal protection. From this perspective, the ‘Hotspot’ had not only become a “struggle for survival” but a de facto legal vacuum.

The Role of the European Union

Keeping thousands of asylum seekers off the Greek mainland at the external borders without access to legal protection can be seen as part of the EU externalisation strategy: The EU-Turkey-Statement aimed to shift asylum procedures and reception outside the European Territory, where EU law does not apply. On the Greek Aegean Islands, i.e. within Greek jurisdiction where EU law should be applied de jure, a legal vacuum was created de facto by the combination of systematic violations of human rights guarantees, measures of deterrence (precarious living conditions and pushbacks) and the lack of effective remedies ensuring the protection of human rights.

The judgment of the Court can therefore be seen as an important landmark for the fight against these violations of human rights at the borders. Unfortunately, the draft to reform the Common European Asylum System by the European Commission points in another direction. The promise “No more Morias” is entirely reversed. Instead, the Greek ‘Hotspots’ and the new Closed Controlled Access Centre Samos (CCAC) that was opened in 2021 now serve as a blueprint: The reform envisages a significant tightening of procedures at the borders by creating a new screening-mechanism after arrival: Art. 9 para. 2 of the proposed Screening Regulation provides for checks for vulnerabilities and special reception needs only “where relevant” and thereby increases the risk of inadequate treatment of vulnerable asylum seekers (see the Statement of Pro Asyl at 3.2. for a detailed analysis). Further, asylum seekers shall not be authorised to enter the territory of a member state during the screening, the asylum border procedure, and a potential removal border procedure – for a total of up to six months (cf. Art. 4 para. 1 of the proposal for a Screening Regulation; Art. 41, 41a of the amended proposal for an Asylum Procedures Regulation). This “fiction of non-entry” opens up new possibilities for Governments to restrict the freedom of movement and access to legal protection.

This provides cause for concern that the creation of de facto legal vacuums at the European borders will possibly be intensified in the future. It becomes apparent that the EU is pursuing a harsh policy of externalising “migration management” that deliberately involves serious human rights violations, such as those documented in this case. By doing so, the EU and its member states are betraying the core European values enshrined in the ECHR.

Disclosure: The authors were part of the legal team of the Applicant, which was composed by members of the Refugee Law Clinic Berlin and I Have Rights and supported by Pro Asyl. The opinions expressed are solely those of the authors.

Kilian Schayani is a legal trainee at the Cologne Higher Regional Court. He studied Law at the University of Cologne.

Max Maydell is a PhD-Student in the fields of Migration and Criminal Law. He works as Research Assistant at the University of Cologne and is the Head of the Scientific Work Group in the Refugee Law Clinic Cologne.