Still Want to Retain the 1.5-Degree Target?

The Legal Space Under Climate Overshoot

The 2025 Emissions Gap Report and the outcome of the first global stocktake clearly reveal that we are not on track to meet the 1.5 °C target under the Paris Agreement (PA). If we still wish to stick to the long-term target, the so-called climate overshoot is becoming inevitable. The IPCC sixth assessment report (AR6) defines climate overshot as temporarily exceeding 1.5 °C up to 0.1 °C (limited overshoot, C1 scenario in AR6 WGIII, p. 1886, Table 14) or by 0.1 °C to 0.3 °C (high overshoot) for a few decades before returning to the temperature target by 2100.

Climate overshoot has been discussed as a compromise between sticking to the temperature goal under the PA and relaxing States’ current emission reductions. However, scientific research has emphasised that climate change and associated risks in a post-overshoot world are different from a world that avoids it. An overshoot could lead to abrupt, irreversible, and dangerous impacts after crossing temperature thresholds of tipping points in large-scale earth systems, even if global warming could be reversed. In addition, given that the reversal of overshoot will rely on large-scale application of carbon dioxide removals (CDR), scientists worried about the overconfidence in the geophysical, economic, and sustainability considerations that may limit the deployment of CDR for achieving the temperature decline.

Against the backdrop, there is an urgency to explore whether international law is future proof for governing the upcoming overshoot and corresponding impacts on Earth systems. This blogpost will unpack the international legal obligations and consequences related to temperature overshoot, transgressing tipping points, and exhausting global carbon budgets.

Broadening the Legal Space – Alternative Compliance with the 1.5 °C Target with an Overshoot?

A fundamental question to begin with is whether temperature overshoots fail to uphold the Paris temperature goal. Basically, the temperature goal under the PA sets a long-term upper limit for global average temperature increase with an aim to ‘significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change (art. 2.1(a)). This goal is further specified by the timeline of achieving net-zero emissions in the second half of this century in accordance with best available science (art. 4.1) and it provides flexibilities for developing States to select the peak and decline emission pathways based on their highest possible ambitions, reflecting common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDR-RC) and in the light of different national circumstances (art. 4.3). At the first sight, the temperature goal per se does not prescribe how the upper limit should be kept, and the deadline of achieving it is flexible, up to 2100.

As the broadly recognised ‘best available science’, the IPCC AR6 concludes that the safest and most equitable pathways that minimise long-term climate risks are limiting warming to 1.5 °C with no or limited overshoot and ensuring rapid, deep, and sustained emission reductions. According to the UNFCCC’s 2024 synthesis report on first global stocktake, States’ emission reduction targets as indicated in their current Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) were indeed compared with the 1.5 °C pathways with no or limited overshoot. However, the considerable gap between the 1.5 °C goal and the prediction of 2.1-2.8 °C increase based on the full implementation of current NDCs demonstrates the extreme difficulty of following no or limited overshoot pathways while leaving flexibilities for adjusting mitigation efforts with national circumstances. The latest scientific projections indicate that, with current CO2 emissions, global remaining carbon budgets in line with the 1.5 °C goal will be used out by 2030, while many developing countries will not even peak their emissions by then. Compared to the long history of industrialisation and carbon peaking in developed countries, the extremely short time for decarbonisation in developing States has raised fairness debates on the unused equitable share of carbon budgets for those with little historical emissions.

Thus, it is arguable that, as long as an overshoot can be reversed to 1.5 °C before 2100, it can be perceived as an ‘alternative compliance’ which upholds the temperature goal while realistically dealing with developing States’ moral claims to emit their fair share. However, to interpret the temperature goal in good faith (Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969) (art. 31.1) as well as in line with the ultimate objective of the UNFCCC (art. 2), the temporary transgression of 1.5 °C could be lawful only when overshoot pathways uphold the environmental integrity of the temperature goal. In other words, the 1.5 °C is a means to an end; the extent to which the ‘alternative compliance’ is valid depends on States’ fulfilment of their obligations to prevent irreversible harm to the ecosystems and the next generations.

Narrowing the Legal Space – Limiting the Lawfulness of Overshoot Due to Tipping Risks

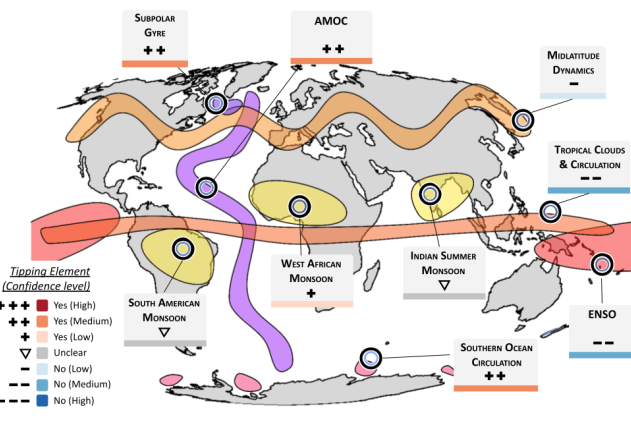

Recent studies reveal that exceeding 1.5 °C could touch multiple tipping points in large-scale Earth systems. Major ‘tipping elements’ range from the ocean-atmosphere (e.g. Atlantic meridional overturning circulation), the cryosphere (e.g. Greenland ice sheet), and the biosphere (e.g. Amazon rainforest). While the overshoot of warming limit may be temporary, some associated impacts cannot be reversed by drawing temperature back to the limit. For some slow-onset tipping elements such as sea level rise, irreversible impacts might be avoidable if the global warming quickly returns below 1.5 °C after the overshoot. But for fast-onset tipping elements such as biodiversity, ecosystem transformation and extinction of species may be irreversible. Regarding the tipping moments, Greenland ice sheet, Barents Sea ice, and low-latitude coral reefs are likely to be tipped as early as just reaching the threshold of 1.5 °C.

To deal with the tipping risks posed by overshoot, in a nutshell, States have obligations to prevent significant environmental harm under most environmental treaties. For planetary boundaries that the tipping elements belong to, the corresponding treaty frameworks (e.g. climate change, marine environment, and biodiversity) apply to the potential harm arising from the crossed tipping points.

Beyond treaty frameworks, States have a customary duty to prevent significant harm to the environment by acting with due diligence obligations, which are a set of obligations of conduct to ensure that all necessary measures have been taken (Pulp Mills, paras. 101 and 197). The standard of due diligence varies depending on the best available science informing the seriousness and probability of harm and States’ capabilities of taking appropriate measures (ICJ AO, paras. 136, 137, 247, and 254). Following the ITLOS’ Advisory Opinion on Climate Change and International Law that concluded the ‘stringent’ standard of due diligence to protect the marine environment from climate change impacts and ocean acidification (paras. 243 and 258), the ICJ’s Advisory Opinion in respect of Obligations on Climate Change confirmed the ‘stringent’ standard of due diligence obligation on climate change (para. 138), which requires States to, among others, prepare NDCs representing their highest possible ambitions aligned with 1.5 °C, take appropriate mitigation and adaptation actions, and co-operate.

There are several challenges of applying due diligence obligations to tipping risks posed by climate overshoot. First, for some tipping elements, where the threshold lies and when it would be crossed are assessed with medium to low scientific confidence (11 out of 16 tipping elements); the early-warning indicators deliver wide time windows and probabilistic signals rather than clear trigger points for preventing irreversible harm. Second, overshoot pathways require revisiting the parameters for assessing ‘highest possible ambitions’ (see also here) and a nuanced due diligence check for those pathways under which the NDCs are not ‘capable of achieving the temperature goal’ (ICJ AO, para. 245) without overshoot. In particular, developing States’ claims to exhaust their fair share of carbon budgets will be at odds with their due diligence obligations to protect their vulnerable populations from the additional warming. Third, regardless of the level of confidence on varying tipping risks, extreme heat and associated risks to the life and health to humans are certainly foreseeable in the overshoot period, so the additional costs for climate adaptation and compensating loss and damage will bring additional challenges to the already very difficult climate finance negotiation.

Contentious Legal Space – Overreliance on Carbon Dioxide Removals (CDR) and Solar Radiation Modification (SRM)

Scientific projections show that the reversal of carbon budget transgression during the overshoot period in later this century relies on an even larger scale application of CDR than the use of CDR for achieving the Paris target. There have been a large number of studies on the moral hazards of lowering incentives to reduce emissions (e.g., here), the bio-physical and sustainability limits and uncertainties regarding the maximum CDR capacity (e.g. here), and the legal limits of implementing CDR (e.g. here). These discussions on CDR in the context of 1.5 °C target are equivalently valid for the context of overshoot, and the reliance on CDR for reversing the surpassed the temperature target before 2100 can only be more speculative.

In contrast to CDR that deals with reversing temperature overshoot, SRM has been suggested to ‘shave the peak’ as the solution to deal with extreme heat during overshoot. Previously being criticised about its limitation of merely dealing with the symptom of climate change – global warming, it seems that SRM can fit the exact need for cooling in the overheat period. However, seeing the long-time debate on the side impacts of SRM so far, (see examples of being neutral, for and against SRM), the discussions on its application for a ‘safe overshoot’ would be equivalently divergent and critical.

Future-proof Law in Case of Overshoot

International law does not outlaw overshoot, but it does require States to aim for no or very limited overshoot and to prioritise immediate and ambitious mitigation. Exceeding 1.5 °C strengthens rather than weakens the due diligence obligations of all States to take all appropriate measures in light of the best available science and their respective capabilities (ICJ AO, paras. 281, 283 and 290). The obligation to co-operate plays a central role in implementing collective climate targets that is based on ‘an equitable distribution of burdens and in accordance with the CBDR-RC’ (ICJ AO, para. 306; see also IACtHR AO, paras. 247-265). Developed States may expedite net-negative emissions and provide extra finance to compensate developing States for not exhausting their fair share of emissions. The argument that overshoot can gain some buffer time or lower the mitigation cost can be rebutted by diversifying and optimising mitigation actions to avoid delay in mitigation. For instance, it would be cost-optimal for the EU to fund mitigation abroad, while China can mainly implement domestic mitigation combined with offering some international finance. In addition, human rights law is widely relevant for the immediate victims during the overshoot and the impacts on next generations during the recovery period.

Failure to minimise overshoot and its impacts may invoke State responsibilities based on the excessive claims for the remaining carbon budget (see also net-zero carbon debt). Some most relevant parameters can be established to test the ‘wrongfulness’. For instance, future policies that may deliberately lock-in overshoot, e.g., licensing new fossil-fuel mining or high-emitting factories (see discussion on governing fossil fuel production and the latest case law), or high reliance on later carbon removals, are likely incompatible with the stringent standard of due diligence.

Climate overshoot is still an uncomfortable topic, as it means the exhaustion of remaining global carbon budgets and a delay of achieving net-zero emissions. However, temporary, limited, and reversable overshoot is going to be the future focal point for global climate action to retain the 1.5 °C goal, if we do not want to exceed it forever. In this sense, climate policymakers need to be informed at least 1) the range and timescale of varying overshoot scenarios; 2) the magnitude of harm arising from crossing different tipping points, the likely timing of occurrence, and the duration; and 3) emission pathways that could reverse global warming levels and the capacity of CDR in those pathways (see more here and here). In addition, understanding overshoot will encourage policymakers’ longtermist thinking about long-term climate adaptation policies, because the adaptation planning needs to cover the entire timespan of overshoot until 2100.

Haomiao Du is an Assistant Professor of climate law and sustainability at the Department of International and European Law and the research group Utrecht Centre for Water, Oceans, and Sustainability Law (UCWOSL) at Utrecht University.