Going Beyond the ICC

The Congolese Accountability Ecosystem

In “International Criminal Tribunals and Domestic Accountability. In the Court’s Shadow”, Patryk Labuda offers a very original analytical framework describing the interplay between the functioning of international tribunals and States’ accountability efforts. In doing so, he challenges conventional wisdom about the concrete consequences of the application of the principles of primacy and complementarity.

The present post focuses on his assessment of the Congolese model of accountability for international crimes. After reviewing Labuda’s main conclusion, the post will offer a broader interpretative framework to understand the Congolese model and nuance some of the claims made by Labuda with regard to the recent results of the fight against impunity in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

The International Criminal Court and the Congolese Government: An Accommodation Story

Several sections of Labuda’s book are dedicated to the analysis of the Congolese domestic response to atrocity crimes. In particular, tracing back the history of the interplay between the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the Congolese government since 2004, the author purports to show that the DRC is an example of how the principle of positive complementarity has come to be redefined as a form of accommodation between the ICC and States. Labuda describes this arrangement as a hands-off consensual relationship based on opportunism and political expediency. In practice, this translates into the ICC selecting its cases with the blessing of the State, whereas the latter launches politically convenient domestic proceedings to portray itself as contributing to the fight against impunity.

This arrangement is criticized by Labuda as contrary to the original counter-hegemonic ethos of international criminal law which is supposed to hold accountable leaders belonging to or associated with the highest levels of State apparatuses. In this view, international jurisdictions should adopt a more confrontational posture vis-à-vis States, characterized by dialectical and at times conflictual negotiation and oversight processes on the genuineness of domestic accountability solutions.

The author’s evaluation in this regard appears to be confirmed by the substance of the Memorandum of Understanding recently signed by the ICC Prosecutor and the Congolese government in June 2023, where what Labuda calls the “ideology of positive complementarity” takes a central role. Without excluding the possibility of further cases taken up by The Hague, it is interesting to notice that the bulk of the agreement centers around the commitment by the OTP to support the efforts of the Congolese judiciary to investigate and prosecute international crimes domestically by offering expertise, capacity-building programs and other facilities.

Understanding the Congolese Accountability Model: The Ecosystem Approach

Without questioning the interest of diagnosing the “shadow” cast by international jurisdictions and their influence on domestic accountability policies, this post submits that especially in a complex, long-standing, and multi-actor context such as DRC, a thorough analysis of the domestic response to international crimes needs to take on a broader interpretative framework.

Adding to and going beyond the study of the two-way interplay between the ICC and the DRC government, we posit that an ecosystem approach fully integrating all relevant actors as well as their strategies, processes, and relationships over time would allow for a more granular and comprehensive understanding of the Congolese model of accountability.

Sketching the Evolution of the DRC Accountability Ecosystem over the Years

For the sake of brevity, we can identify three phases in the evolution of the DRC’s accountability ecosystem.

The first one covers the period starting with the self-referral to the ICC (2004). As correctly reconstructed in the book, this is the period in which the groundwork was laid for the Congolese cases that ended up being prosecuted in The Hague and the ICC played a paramount role as the main counterpart of the Congolese government in its fight against impunity. During the following years, a few NGOs began supporting the Congolese judiciary with capacity-building programs and offering judicial assistance to victims in the first domestic trials for international crimes. The number of these trials as well as the quality of the judgments were very limited.

Between 2010 and 2011, acting under chapter 7 of the UN Charter, the Security Council mandated the establishment of experts’ units within MONUSCO (UN Mission in DRC) – the prosecution support cells (PSCs) – tasked with supporting the investigations carried out by the Congolese justice authorities. In 2011, the Congolese government signed a memorandum with MONUSCO mandating the PSCs to provide the Congolese judiciary with technical advice and logistical support needed to conduct criminal investigations and prosecutions. This represented a major paradigm shift in the accountability ecosystem, embedding international expertise into the work of domestic magistrates. This led to what we can consider as the second phase in the evolution of the DRC model, spanning from 2010-2011 to 2016. This period saw a slight increase in the number and quality of judicial proceedings, even though the pace of change was slow, partly due to some resistance by national prosecutors, partly due to the lack of effectiveness in international support, given the little coordination among actors and the absence of commonly agreed-upon priorities.

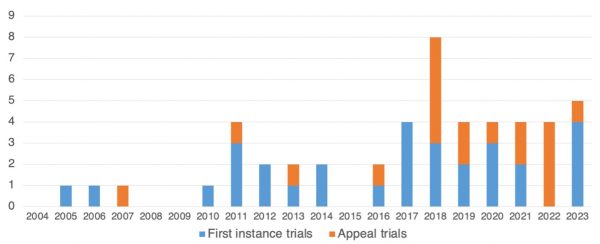

Then, in 2016, a few parallel developments marked a further qualitative turning point. Among them, the establishment by Congolese prosecuting authorities of a prioritization strategy with a list of “priority cases” per province, and the set-up of provincial coordination mechanisms called Task Forces (Cadres de concertation) gathering all the actors of the accountability ecosystem, namely MONUSCO, other UN agencies such as the UN Development Program, national judicial authorities as well as international NGOs such as TRIAL International, Physicians for Human Rights, Panzi Foundation, or Lawyers without Borders. The Task Forces – initially created only in the eastern provinces, but recently extended to the Kasaï region – are animated by the PSCs and have become the main strategic and operational forum for the fight against impunity, being able to coordinate and harmonize the efforts of all different partners. The Task Forces regularly meet to review, evaluate and update the status of the priority cases and to discuss the progress, challenges, and evolution of judicial proceedings. On this basis, they decide how to best deploy the necessary expertise to support Congolese authorities. Starting from 2017, the rate of judicial proceedings has considerably increased, as well as the quality of the judgments according to an independent report covering the period from 2015 to 2019. That is why we can consider the period from 2016 up to now as the third phase of the evolution of the DRC accountability ecosystem. Contrary to the first and second phases, the ICC has become a minor actor in light of its decreased presence in the country compared to the preeminence of the Task Force actors.

Here-below a table visualizing the number of first instance and appeal trials for international crimes held per year since 2004 in the province of South Kivu – one of the most affected by atrocity crimes and admittedly the region where the provincial Task Force has had the most effective impact since 2016.

Drawing Some Tentative Conclusions

In light of the described evolution, Labuda’s main conclusion on the outcomes of the DRC accountability model merits further scrutiny. In particular, the claim that the “DRC’s accountability landscape is better understood as a case of ‘unintended diversionary complementarity’, which captures the phenomenon of state authorities trying lower-level, politically unconnected perpetrators for isolated human rights violations while ignoring systematic crimes condoned by senior state officials” (Labuda, page 246) needs to be nuanced.

The majority of the references used for the Congo case study in the book date back to the second phase of the accountability ecosystem, thus justifying a healthy skepticism. But we submit that the more recent evolution of the Congolese ecosystem paints a more promising picture, albeit with huge challenges ahead.

If the reference point is the 2014 Minova trial discussed at length in the book, Labuda’s conclusion seems warranted. But there have been many trials in more recent years exemplifying opposite trends. A case against a sitting parliamentarian, several cases against army officers and very recently against an army general and a police high commander for the most infamous crimes committed during the Kamuina Nsapu crackdown by the Congolese government, several cases against the leaders of armed groups. All of these trials were held against high-level suspects from all sides (armed groups and State forces) on charges of crimes against humanity or war crimes, involving complex mass crimes with an average of around 100 victims per case. And most of them were possible after strong legal and political pressure by civil society and Task Force actors in order to overcome powerful interests protecting the suspects.

This is not to say that such power struggles always end up on the accountability side. Far from it. There have been numerous instances in which justice remains elusive because of power dynamics within the domestic political realm. Assessing the ability and willingness of the Congolese judiciary involves a nuanced assessment to be done on a case by cases basis, considering that the Congolese political and justice authorities are not a monolith. That is why fora like the Task Force are exactly the place where coordinated and iterative dialogue with national authorities – on issues such as prosecutorial strategy, justice capacity building needs, evaluation of the steps taken to advance ongoing proceedings as well as to overcome existing obstacles – takes place.

The continuous negotiations and push-pull bargaining with national authorities that the ICC abandoned in DRC – according to Labuda’s account – has in fact taken a different shape through the existence of coordinated networks within the national accountability ecosystem.

Enormous challenges remain to be tackled. There are still too many serious crimes that remain beyond the justice system’s reach and a complete lack of accountability for crimes committed before 2003 in the absence of a specialized judicial mechanism. Moreover, the persistent dependence of the Congolese judiciary on international support is cause for concern as well as the de facto monopoly of military jurisdictions over international crimes despite recent efforts to increase the role of the civilian justice authorities.

But, in conclusion, we would suggest that the evolution of the DRC accountability model in the past two decades cannot be reduced to national political elites promoting “authoritarian power at the expense of affected populations’ aspirations for emancipatory justice” (Labuda, page 10), but instead represents a very interesting and innovative story of a domestic accountability ecosystem that merits further analysis and study.

Daniele Perissi holds a LLM in International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Law and is Head of Great Lakes Program at the NGO TRIAL International.

Guy Mushiata is a qualified Congolese lawyer and is DRC National Coordinator at the NGO TRIAL International. He is based in Bukavu (South Kivu, DRC).