Who Gets to Speak in the Israeli University?

Universities often claim to be bastions of free inquiry, including in research and in the classroom. But in Israel today, that claim rings increasingly hollow. While pockets of academic freedom exist, these often track the lines of Jewish supremacy, protecting some while punishing others. Since October 2023, campuses have reproduced the state’s broader regime of silencing. This unequal distribution generates a kind of speech apartheid, or – as Adi Mansour calls it in his contribution to this symposium – an “apartheid of knowledge”.

Below, I start from my own experience. To be a tenured Jewish Israeli scholar at an Israeli research university still provides a shield for free speech. And yet, for those who are not as protected, including non-tenured and non-Jewish faculty, the situation may be entirely different. Most importantly, for Palestinian students, the costs of criticizing the state have in the last two years become significantly more immediate and severe.

With some distance from my home institution, I have been preoccupied with the question of whether and how universities such as my own can preserve spaces of equality. Equality in the classroom is not only a fundamental moral and political principle the university must uphold. It is also an epistemic precondition for higher learning.

Relative Shelter

Since August 2024 I’m in Berlin, first on sabbatical and now on leave from my University, the University of Haifa. Recently, I served as a legal adviser to the NGO “Physicians for Human Rights” in Israel (PHRI) and helped in writing their recent “Health Analysis of the Gaza Genocide.” When I realized that the report was scheduled to be published during a family visit to Israel, I had a moment of cold feet.

The Israeli Knesset is currently in the process of voting on legislation that will make any such work a criminal offense. According to the Bill, a maximal five-year sentence is attached to providing information that can serve international or foreign courts and tribunals. While the Bill has not yet been adopted, I was afraid of being questioned or perhaps even arrested by Israeli authorities, perhaps at the airport, perhaps elsewhere. As I have argued elsewhere, the new legislation is a potential death blow to the independence of international legal research in Israeli universities. Against this backdrop, I suspected that the report could test the limits of my academic freedom.

Contrary to the scenarios I had imagined, my visit to Israel went smoothly. No administrator at my university questioned my activity. The fact that my academic freedom is protecting me for now, despite a generally very hostile environment towards the underlying position, is to the credit of the university which provided me with an academic home since 2016. Outside the university, of course, ramifications against PHRI, and other organizations, remain likely.

Speech Apartheid

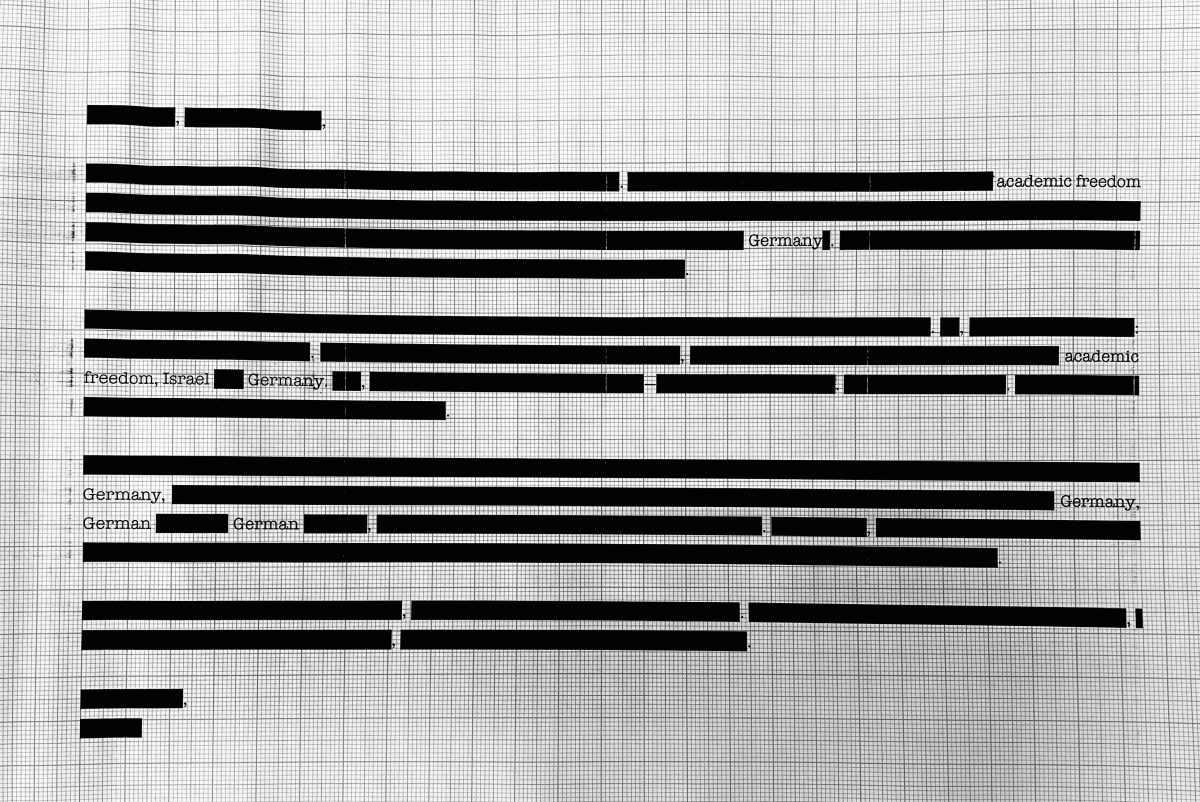

This seemingly happily-ending personal anecdote is to be contrasted with stories from other, less protected parts of Israeli academia. Such stories populate the report published by “Academia for Equality” in June 2024 titled “Silencing in Academia Since the Start of the War”. The report exposes the scale of persecution directed at Palestinian students, citizens of Israel who have been silenced between October 2023 and June 2024. Expressions of dissent, or even basic empathy for the Palestinians in Gaza have been swiftly and unfairly punished.

At Bezalel Academy of Arts, seven Arab Palestinian students were suspended and fourteen brought before disciplinary committees over social media posts. Fifty-seven others sought psychological support in the wake of an atmosphere of fear. At the Technion and at Ben-Gurion University, Palestinian students were suspended or expelled for comments on Facebook. At Haifa University, entire groups of students were summoned for disciplinary hearings after posting critical remarks online. While I don’t have all the necessary information about every case, the pattern is alarming, and surely raises significant concerns about due process.

One Palestinian student described being suspended after stating, in a classroom discussion, that rape is an atrocity committed by both Hamas and Israeli soldiers. Jewish classmates apparently reported her directly to the dean, illustrating “a permissive atmosphere in which informing on others is encouraged…”. Within twenty-four hours she was facing disciplinary proceedings, and reinstated only after intervention by Adalah lawyers. The experience left its mark. “I will no longer express my opinions,” she said, “because I understand what could happen to me and to other Palestinian students here” (p. 9).

Survey data set out in the report confirm what the case files show. Ninety-seven percent of Palestinian students report that their universities are hostile to them. Eighty-seven percent believe they are under surveillance. Seventy percent of young Palestinians have stopped posting or engaging on social media altogether, fearing arrest or disciplinary action (pp. 4-5). Palestinian students in Israel are being taught that their identity and political voice are liabilities. They learn that empathy can be criminalised, that grief can be framed as treason, and that their presence on campus is tolerated only on condition of silence.

What ties my own experience to these stories is the structural distribution of speech rights – be it freedom of expression, or academic freedom – along the lines of Jewish supremacy. I can (still) speak freely. I can (still) provide legal advice on a sensitive matter to PHRI. Palestinian students, by contrast, have come to believe that they can be suspended, interrogated, or expelled for a social media post, for a single sentence in a classroom, or even for an expression of grief.

The asymmetry produces a paradox, familiar to Palestinians for generations, but recently brought into even starker relief. On the one hand, it risks recentring critique in the voices of Jews, who can speak with relative safety and thus become the “legitimate” conduits of dissent. Here in Germany, it is certainly the case that Jewish-Israeli scholars often become the more legitimate critics of Israel, in dynamics that overshadow and marginalize the most important Palestinian voices. Sami Kahtib commented on this clearly and sharply at the launch of the “Association of Palestinian and Jewish Academics” in Berlin in February.

On the other hand, it is precisely because of that asymmetry that Jewish scholars and students have a duty to speak: to refuse to let a system that criminalises Palestinian expression persist unchallenged, and to create a space in which Palestinians who choose to speak are not alone. To remain silent in the name of academic neutrality is to collude with the legal and institutional architecture that enforces this hierarchy.

To be sure, in the two years since October 2023, Palestinian students have also spoken for themselves on campus, often with enormous courage. To paint a picture of their successful silencing would therefore be misleading. Here too, relatively protected faculty can have a crucial role in responding to their expressions, creating conditions in which they can be heard, and meeting them where they are. The project “Eyes on Gaza”, organized by colleagues, has been one remarkable way of doing so.

Methodological Equality in the Classroom

Some may believe that actively supporting the speech of Palestinian students may disadvantage Jewish students. That should not be the case.

The university classroom must be committed to methodological equality. If the task is to advance the knowledge of all those sitting in the classroom, no particular viewpoint or positionality should have an a priori preference. Indeed, equality among students is not only a moral, political, or legal requirement; it is a precondition for the basic mandate of higher learning, especially in the humanities and social sciences, where we seek to examine social phenomena. When the “outside world” is structured around Jewish supremacy, protecting such bubbles of methodological equality can be radical in and of itself.

But is that even possible within an Israeli university? Over the past two years, many Jewish students have been serving in reserve units of the Israeli Military, including in Gaza. They have returned to classrooms straight from the battlefield – a battlefield that, in my judgment, has become a site of genocide. And as Nahed Samour recently explained, Israeli universities have supported them, for example through alternative and easier examination, indirectly supporting Israel’s actions in Gaza.

Can Palestinian students seriously be expected to speak their minds in front of reserve soldiers fresh from the battlefield? Can faculty even be expected to facilitate an open discussion among these different groups? Israeli student bodies are often far to the right of law school faculties. The latter may therefore feel a kind of bottom-up pressure to shut up. The risk is to be recorded or reported on by right wing organizations such as “Im Tirtzu”, and possibly suffer shaming on traditional or social media.

Jewish students have often expressed discomfort and dismay when sharp criticism of Israel has been voiced in classrooms. At times they may experience such discomfort as discrimination, demanding that the discussion be shut down. When a professor voices criticism, they may often feel that they cannot challenge the professor’s viewpoint because of the underlying institutional hierarchy. These are all understandable concerns. Yet, faculty should not accept that solidarity with Palestinian students by definition threatens Jewish peers.

The task is to meet Jewish students, too, where they are: not by softening criticism, but by extending an invitation to dialog. In such a dialog in the classroom setting, students who come fresh from roles as soldiers on a genocidal battlefield are always to be held innocent. It is contrary to the role of a university to incriminate anyone. Their viewpoints too should be encouraged and supported. At the same time, students from all backgrounds should be expected to hear viewpoints that cause them discomfort, and participate in their reasoned examination.

In Israeli universities, and elsewhere, we must remember that the measure of academic freedom is not comfort but the possibility of intellectual confrontation. If the university cannot sustain both sharp criticism and mutual respect, it is not only complicit in the hierarchies that silence those who most need to be heard. It can no longer be a place in which knowledge is produced.

This post may seem like it tries to serve a portion of naïve liberalism at a time when liberalism seems to be collapsing globally, let alone in Israel. What I have learned in my time abroad, is that even the seemingly most solid centres of liberalism may compromise methodological classroom equality. Conversely, even when the social surroundings seem to be particularly unamenable, pockets of methodological equality may emerge.

Preserving them as part of our universities can nowhere be taken for granted, and the task nowadays requires effort and determination, wherever you are.

I thank Orna Ben-Naftali, Gil Rotschild Elyassi, Lihi Yona, and the editors of this symposium for their helpful comments on a previous draft of this post.

Itamar Mann is a Humboldt Fellow at Humboldt University and Professor of Law (on leave) at the University of Haifa. His work spans international law, human rights, migration, climate, and international criminal law, approached through legal and political theory. He is currently writing Liferaft Manifesto: Democratic Survivalism and the Sea (Cambridge Elements) and has served as President of Border Forensics since 2021.