Chinese Legal Warfare in the Ryukyus

A New Campaign of “Island Hopping” from the Senkakus to Okinawa

On April 1, 1945, thousands of American troops landed on Okinawa, marking the brutal finale of a years-long campaign of “island hopping” against Japan. The strategy used islands as stepping stones to close in on Japan, setting the stage for a full-scale invasion of its mainland. The war ended before that invasion could be launched, but it took another 27 years before the 1971 Okinawa Reversion Agreement would return the Ryukyu Islands to Japanese sovereignty.

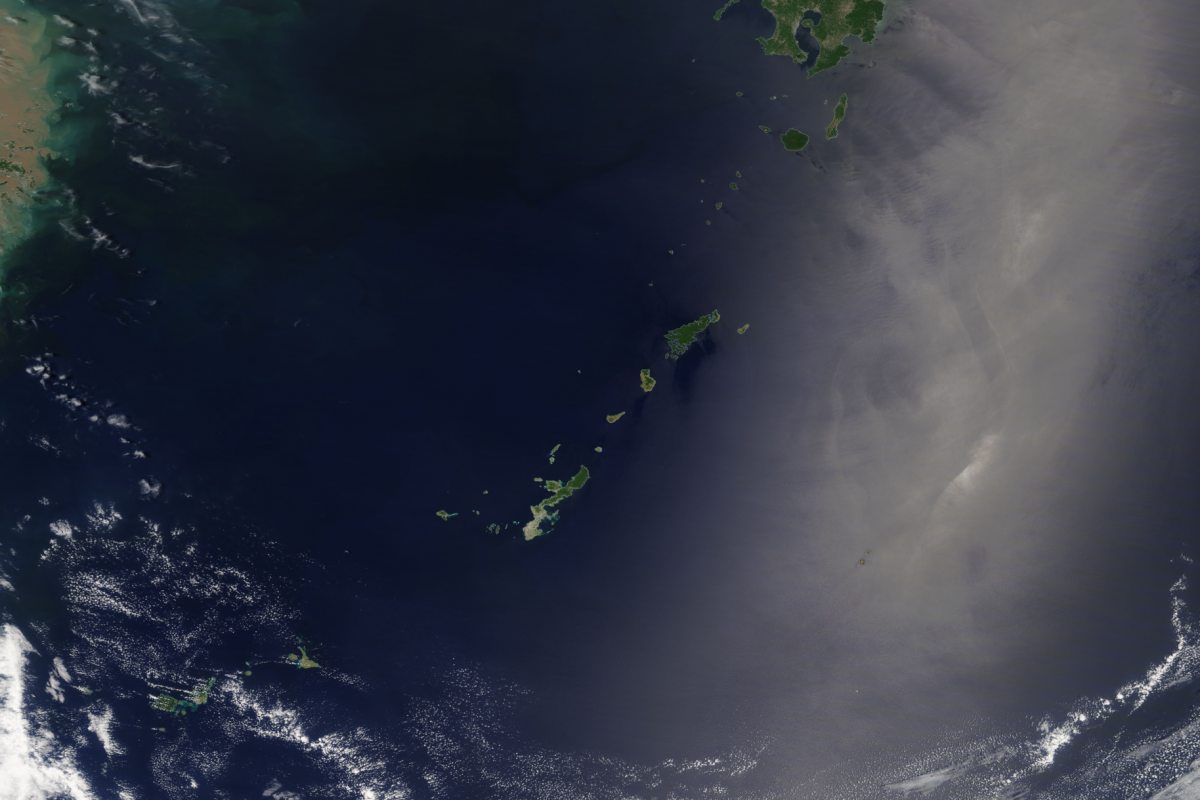

This contribution will argue that China is conducting a new “island-hopping” campaign, beginning with a territorial dispute concerning the small Senkaku Islands, before escalating more recently to challenging Japanese sovereignty over the large and populated Ryukyu chain. In light of China’s response to recent comments by Japanese Prime Minister Takaichi on Japan’s right to self-defence, the present analysis will examine how China’s leveraging of international law may be paving the way for military action.

The Senkaku Islands

The Senkaku Islands, known by China as the Diaoyu Islands, are the last remaining area of territorial dispute between Japan and China. Although uninhabited, and totalling no more than 7km², they hold significant potential economic and strategic value. Japan’s claim to the islands went uncontested by China until the 1970s, following the publication of a 1969 report suggesting the existence of large reserves of oil and natural gas in the islands’ EEZ. China has claimed the Senkakus through the 1992 “Law on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone”, and more recently, through the 2011 “Diaoyu White Paper”, which claims the islands are an “inseparable part of Chinese territory” under international law.

Under the 1943 Cairo Declaration, given effect in the Japanese Instrument of Surrender through the Potsdam Declaration, “all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa, and The Pescadores, shall be restored to the Republic of China”. China argues that the Senkaku islands are among these “stolen” territories.

Japan contests that China has no historic claim to the islands, with the territory being terra nullius prior to Japanese incorporation in 1895. Furthermore, the islands were not included in the territories concerning which Japan renounced “all right, title and claim” in Article 2 of the 1951 San Francisco Treaty. The said treaty did not mention the Senkaku Islands by name at all, although they fall within the longitude and latitude of the area under U.S. Administration under Article 1 of the Provisions of the Government of the Ryukyu Islands, and thus were returned to Japan when the 1971 Okinawa Reversion agreement restored Japanese control over the islands. American administration prior to the reversion is evidenced by the U.S’s extensive use of the Senkakus as a firing range, with no evidence of objection from Chinese authorities. Although China disputes the validity of the San Francisco Treaty as a non-signatory, the absence of any claim over the islands until the 1970s undermines its arguments.

Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that China has avoided seeking a resolution to the dispute at the ICJ. Instead, to weaken Japan’s sovereignty claims over the Senkaku Islands, China has challenged Japan’s “effective control” over the territory. Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) vessels frequently sail through the area and interfere with Japanese fishing vessels, mirroring its “grey zone operations” in the South China Sea. This tactic is intensifying, with 2025 breaking the record for CCG presence in the area for the fourth consecutive year. Japan has responded to these incursions promptly, with its Coast Guard issuing warnings to leave the area, as part of its strategy of “proactive restraint”. Given that Japan enforces its sovereignty through this manner, but also through taxation, fisheries management, and law enforcement, Chinese attempts to demonstrate a lack of Japanese “effective control” have seen limited success. At any rate, these CCG operations would lack evidentiary value, since they have occurred after the crystallisation of the territorial dispute on 30 December 1971, when China made its first official claim to sovereignty over the Senkakus. Such acts to strengthen a party’s legal position after this critical date cannot be considered by international courts (Indonesia/Malaysia case, paragraph 135).

However, there is a more troubling interpretation of China’s actions. By bringing Japan’s current control of the islands into question, it may be legitimising future action. China has claimed that its sailing of ships through the surrounding waters represents “a routine presence” and illustrates the exercise of jurisdiction. If the ongoing situation of the islands is reshaped into Chinese administration, or at least an active dispute, rather than Japanese control, a landing of Chinese troops on the islands could be characterised as merely a continuation of the status quo, rather than a dangerous affront to it.

China seizing the Senkakus by force is not far-fetched. Given that the islands host no permanent Japanese soldiers, the risk of an incursion successfully seizing the islands without firing a single shot poses a significant legal challenge for Japan. Chinese activists have already landed on the islands multiple times before being arrested and deported by Japan. However, if Chinese police or military forces were to occupy the island, a swift response may not be possible. Japan’s coast guard lacks the authority and practical strength to repel an armed occupation. On the other hand, domestic and international law dictates that the Japanese Self Defence Forces (JSDF) would only be able to use force in the event of an “armed attack” or “existential crisis”. Additionally, only an “armed attack” would trigger U.S. mutual defence obligations under Article 5 of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. Whether a bloodless Chinese occupation of disputed small uninhabited islands would meet the threshold of an “armed attack” would be highly controversial. Such an action could be characterised only as a localised border dispute [see Ethiopia’s Claims 1–8 (Partial Award), para. 11]. This may then not fall within “the most grave forms of the use of force”, as envisaged in the Nicaragua judgment (para. 191). Even taking the legality of the use of force to repel Chinese forces for granted, Japan may be hesitant to gamble an all-out war. The picture would be further complicated if such an operation was conducted by ununiformed and anonymous soldiers to give China plausible deniability, akin to Russia’s “Little Green Men” used in the takeover of Crimea. These tactics are not alien to China, which commands a maritime militia force that has been dubbed the “Little Blue Men” in reference to the similarities between both states’ attempts to circumvent state attribution.

Chinese officials might only be posturing or appealing to domestic audiences, but it is very plausible they are also constructing a legal casus belli for a possible future occupation of the islands. Such an operation would allow China to test the U.S.’ determination to defend its allies in the region, possibly before a Taiwan invasion. Since multiple U.S. administrations have stated that the Senkakus are protected under Article 5 of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, a weak American response would damage the trust of U.S. allies in Asia, to China’s benefit.

The Wider Ryukyu Chain

Moving past the Senkakus, China has increasingly challenged Japanese sovereignty over the wider Ryukyu archipelago, home to 1.5 million people. The growing field of “Ryukyu Studies”, which challenge the legal and historic foundations of Japanese sovereignty over the Ryukyus and emphasise Chinese connections to the islands, have attracted the focus of Chinese academics. Meanwhile, Beijing has also employed human rights rhetoric to paint Japan as a colonial occupying force. Its deputy permanent representative to the UN recently called on Japan to “stop prejudice and discrimination against Okinawans and other indigenous peoples” during a debate of the UN General Assembly’s Third Committee. Despite maintaining a position of strategic ambiguity, avoiding official state comments on Japanese sovereignty over Okinawa, a number of prominent Chinese officials have signalled support for the “undetermined status of Ryukyu” to various degrees. This includes a former ITLOS judge, a two-star general, and even President Xi himself. Following the recent diplomatic row with Japan, Chinese state media launched an intensified campaign to this end. This rhetoric has found crucial support in Chinese academia (here, here, and here), which has questioned Japanese sovereignty over the Ryukyu Islands through several revisionist legal arguments.

Firstly, Chinese commentators and scholars have argued that the 1971 reversion of the islands back to Japan was invalid by challenging the validity of “residual sovereignty”. Under Article 3 of the San Francisco Treaty, Japan would “concur” to any proposal placing the Ryukyu Islands under a U.S. administered UN trusteeship. However, the trusteeship ultimately never materialised, with the U.S. opting to maintain a direct military occupation. It is argued that by agreeing to detaching the Ryukyus as a trusteeship, Japan necessarily lost its sovereignty over the islands. Consequently, Japan could not have “residual sovereignty” over the islands during the American occupation until true sovereignty was restored in 1972. This is bolstered by reference to Article 76(b) of the UN Charter, which states that the objectives of a trusteeship include the “progressive development towards self-government or independence”. Thus, it is argued that the reversion of the islands to Japan in 1972 was unlawful given that Japan had no legal claim to the territory, having relinquished its sovereignty over the islands, particularly when the Ryukyu population was not given an opportunity to exercise its right to self-determination.

These arguments face significant hurdles under international law. Even taking for granted that implementing a UN trusteeship would have nullified all Japanese claims to the Ryukyus, such a trusteeship was never ultimately implemented since the U.S. kept the islands under direct occupation until their reversion to Japan. Moreover, Japan was never made to “renounce” its sovereignty over the Ryukyus, as it did for other territories in Article 2 of the San Francisco Treaty. It is also doubtful whether the reversion is inconsistent with the right to self-determination, since less than 5% of the local population support independence.

Secondly, China has rejected the San Francisco Treaty as void, as China was not involved in its negotiations and is not a signatory. China is not directly bound by the treaty in accordance with pacta tertiis. Nonetheless, China cannot rely on its non-involvement to question the effect of the treaty on Japan and the 48 allied countries that were signatories.

China argues that by virtue of its exclusion, the San Francisco Treaty constitutes a separate peace with the Axis powers, in violation of the 1942 UN Declaration. However, even if one was to accept the declaration as binding, this is a dubious argument as fighting had already ceased 7 years prior to the signing of the San Francisco Treaty, and China was excluded from treaty negotiations because at the time it was unclear whether the nationalist or communist government was legitimate.

China has increasingly focused on the “Ryukyu Question” as a potential point of vulnerability for Japan. While it may be invoked as merely political leverage, it could also be laying the groundwork for future attacks on military targets in the Ryukyu Islands. If China was to launch a full scale invasion of Taiwan, strikes on U.S. bases in Okinawa would be highly likely, whether pre-emptively, or following U.S. entry into the war. China may then seek to frame such strikes as an anticolonial use of force against illegal occupation forces, rather than an attack on Japanese sovereign territory. Such a scenario can hopefully be avoided, but by building up the legal framework through which an armed attack could be justified, China signals its willingness to strike Japan should it, or the U.S., interfere with a potential cross-strait military operation against Taiwan.

Conclusion

China’s legal island-hopping strategy echoes the American campaign fought over 80 years ago. No shots have been fired, yet China has moved from contesting the small uninhabited Senkaku Islands to launching an escalating push against Japanese sovereignty over the entire Ryukyu chain. The next target appears to be the integrity of the jus ad bellum regime; Chinese diplomats have recently threatened to revive the UN Charter’s vestigial enemy states clauses (i.e. Articles 53 and 107) against Japan to sidestep the prohibition on the use of force. Although these efforts have so far remained the subject of abstract legal discussions, the Chinese strategy may well be setting the stage for the kinetic use of force.

Oliver Fujioka ist ein Student der Rechtswissenschaften an der University of Cambridge.