Building Critical Spaces: The Palestine Project and the Future of Legal Education

An Interview with Dr. Souheir Edelbi

I am honoured to be speaking with Dr. Souheir Edelbi, one of the founders of the Palestine Project and a legal academic whose work sits at the intersection of pedagogy, international criminal law, decolonial thought, and lived experience. As a scholar with roots in a region so often spoken about but rarely with, Souheir brings not only intellectual depth but a grounded sense of responsibility to her work and to the students she mentors.

To begin, could you tell us more about the Project itself – its goals, its guiding principles, and how it seeks to support students and academics navigating the intersection of education and global injustice?

Thank you very much for the warm invitation and for this conversation. It is a privilege to share some of my reflections on The Palestine Project (the PP). I want to note that there are certain challenges in speaking about an institutional project on Palestine, particularly of who can speak and how they are allowed to speak. For this reason, it is worth mentioning that I am speaking from my perspective as an Arab, Muslim and junior academic and what I share here is grounded in my personal experience and observations. It does not necessarily reflect the institutional aims or perspective of the PP.

The PP was launched by the School of Law at Western Sydney University (WSU) in February 2024, with the support and leadership of the Dean, Professor Catherine Renshaw. It emerged as a direct response to the unfolding catastrophe in Gaza, which was having a severe emotional and distressing impact on law students and staff who were bearing witness to Israel’s intensifying assault on Gaza, especially Palestinian students who were personally impacted. In these circumstances, it became critical for us as a law school to double our efforts to ensure our school was a supportive and welcoming space for our students. That is why the PP is focused on two main aims, namely, supporting student well-being and ensuring pedagogical support for academics on Palestine. For context, WSU has a culturally diverse student body, with Palestinian, Arab, and Muslim students making up a significant portion of our student community. This has had the inevitable consequence that the impact of Israel’s atrocities in Gaza has been painfully and acutely felt throughout our community.

My involvement in the PP has therefore been fundamentally about creating a space of care and community for our students and for each other to express our solidarity with the Palestinian people. For me, this has been especially important because Gaza has had such a distressing impact on Palestinian students and other students of colour who are typically racialised as brown, Black or Muslim. Critical to escalating well-being support was the feedback we received from students to enact a space where they felt supported to talk about Palestine in the classroom and with each other. Based on this feedback, and seeing how distressed students were struggling to make sense of the atrocities in Gaza and the West Bank, we chose to prioritise disseminating knowledge of Palestine’s legal, historical and cultural context. For me, this speaks to the importance of legal education in creating pathways to knowledge and critical thinking, but also support for students through a trauma-informed approach as they navigate the emotional and cognitive weight of learning in times of profound catastrophic violence.

To this end, the PP has a dedicated webpage that serves as a central hub of credible resources and knowledge for our students. This includes an introductory reading list, alongside a more extensive compilation of readings on international law and the question of Palestine, which has been generously curated by a group of colleagues at Melbourne Law School. Importantly, these materials are open-access and so freely available to staff and the wider public. Beyond resources, we have hosted several international lawyers, scholars, educators and writers in relation to international legal developments on Palestine and comparative representations of genocide in the media. In this sense, the PP is both a critical tool to support student well-being and a reminder of the vital role that legal education plays in times of catastrophic injustice. Of course, this is not a new or exceptional approach; rather, it extends existing principles of inclusive education to students navigating grief, rage, trauma and the lived reality of genocide in Gaza. Therefore, in my role as a convenor of the PP, I have focused on creating the possibility of a space to refuse efforts to make Palestine the exception to progressive legal education.

The second aim of the PP is to defend academic freedom by insisting on space to discuss Palestine, as one of the most difficult issues currently confronting academics and educators worldwide. Alongside wider global efforts to make Palestine visible, the PP documents and archives critical conversations that law faculty staff are having on Palestine, while creating a space to offer pedagogical and curriculum support for staff working on Palestine. Relatedly, it encourages and invites conversations and questions about Palestine both within teaching and in shaping law curricula. Attacks on academic freedom are having a serious chilling effect on whether academics feel safe to talk about Palestine in the classroom, but also whether students feel safe to speak, question and share reflections. I see the PP as fundamentally a site of resistance against the dehumanisation of Palestinians as a people and the epistemic erasure of Palestine as a site we can learn from. Gaza demands an urgent reckoning of our ethical responsibilities as educators and academics to refuse institutional silence, recognise Palestinian suffering, and to centre the realities, knowledge and perspectives of Palestinians within legal education and scholarship.

I would add that the PP is only one initiative among other initiatives committed to promoting knowledge and education on Palestine, such as ‘Visualizing Palestine’, which has developed a comprehensive visual archive of infographics and interactive learning tools, ‘to visually communicate Palestinian experiences’. In a similar vein, ‘Law for Palestine’ has compiled an intent database containing over 486 examples of statements of genocidal intent by Israeli leaders and journalists. The PP has also emerged within the context of global student solidarity, as illustrated by anti-genocide protests on campuses around the world. In this sense, I see my role in the PP as part of a broader struggle to promote meaningful accountability and advance epistemic justice by contributing to the preservation of Palestinian knowledge, history, culture.

Finally, underlying the PP is the importance of upholding international law, accountability and democratic values, without exception. From a TWAIL perspective, I see the PP as working actively against the colonial, racist and Eurocentric foundations of international law by enacting a form of repair and insisting on the inclusion of Palestine in teaching, academic discourse and scholarship. Whether international law per se is dead is a question worth reflecting on, but for now we have chosen to ground the PP in important legal decisions such as the ICJ’s Order of 26 January 2024, which found it plausible that the Israel’s actions in Gaza may amount to genocide under the 1948 Genocide Convention, and the ICJ’s Advisory Opinion of 19 July 2024, which made it clear that Israel’s occupation of the OPT is unlawful and that Israel must dismantle the settlements and remove settlers from the OPT. The Advisory Opinion is a landmark ruling in that it requires all UN member and observer states not to recognise the unlawful situation created by the occupation and to refrain from providing aid or assistance in maintaining Israel’s illegal presence in the OPT. These are not abstract rulings but critical tools that our students can learn to question and reflect on as they grapple with the limits and potential of international law in confronting Israel’s entrenched impunity, as well as the genocidal and extractive violence of settler colonialism.

Can you share what motivated the establishment of the Palestine Project? What specific needs was it responding to, particularly in the academic environment following the events of October 2023 and the escalation in Gaza?

This is a difficult question because it speaks to the unbearable horror in Gaza, and the ways that Palestinian dehumanisation reverberates as a broader structural dismissal of Palestinian, Arab and Muslim lives. It is out of this pain, and in response to students’ urgent needs, that the PP was established during Israel’s genocidal escalation in Gaza. From early conversations with students, it became clear that Gaza was already in the classroom. Students were preoccupied with the unfolding genocide, yet classes refrained from acknowledging it. These students perceived the learning environment as silencing conversations about Gaza, which led to disengagement from the classroom, raising questions for us about the purpose of legal education. I want to emphasise that this silence was not because of any individual academic, but rather the product of broader selective and recurring omissions on Palestine and a ‘business as usual’ approach to official university communications, which implicitly treated Palestine as the exception to inclusive education, but also signaled professional risks for academics and educators. The weight of this institutional silence created such a profound disconnect between the lived reality of Gaza and how our students were experiencing the classroom. Although Gaza was hypervisible in students’ conversations, many students felt there was no space to bring those conversations into the classroom, reinforcing the perception that the learning environment was actively perpetuating the Palestine exception.

For instance, some students pointed to the stark difference in institutional treatment between Palestine and Ukraine, citing a statement by the previous Vice-Chancellor in support of the people of Ukraine that acknowledged, in strong and robust language, the right of Ukrainian people to ‘freedom’, ‘self-determination’ and ‘access to education’. The statement extended to an effective and immediate boycott of all Russian universities and institutions. For students of colour, the lack of comparable support for Palestine, particularly as universities in Gaza were being systematically destroyed, was perceived not merely as an omission or silence, but as a manifestation of anti-Palestinian, anti-Arab and anti-Muslim racism. It reaffirmed how little structural power these students had within the university, despite constituting a significant portion of our culturally diverse student body, in contrast to Zionist students and staff, who represent a very small minority. I don’t believe it is a stretch to say that, in downplaying the genocidal reality in Gaza and consequently trivialising the lived experiences across these communities, the university environment became a site of institutional trauma for students and staff of colour in that it contributed or compounded pre-existing racial and intergenerational traumas.

This experience of racial trauma resonated with me personally as the 9/11 attacks in New York occurred when I was studying law as a visibly Muslim brown woman, and the dehumanising violence it unleashed on Muslim communities in the West left a profoundly scarring impact on me. I remember speaking out in an international law class against the West’s invasion of Iraq, only to be harshly shouted down by a white male student. The teacher did not intervene, and the memory of how small and unsupported I felt has stayed with me. I experienced the law classroom at the peak of anti-Muslim and anti-Arab racism in the West and it offered little refuge or support. Gaza triggers and compounds the memory of that painful trauma and the responsibility to support and care for students in this moment of genocidal horror in Gaza. As the PP has developed, it has become such a vital and needed space for staff and students to collectively witness, process and respond to Israel’s genocidal killing and starvation of Palestinians. Indeed, it has allowed us to reflect on, and navigate, this collective trauma as Arab, Palestinian, Muslim students and staff; to process our grief together and honour our Palestinian siblings and their struggle for liberation.

Universities are often idealized as bastions of free thought, critical inquiry, and democratic values. Yet, in practice, they are also deeply embedded within State structures – financially, politically, and ideologically. This becomes especially visible when expressions of solidarity with Palestine come under intense scrutiny, leading to suspensions, investigations, event cancellations, or silencing of faculty and students. Given this tension between the university’s symbolic role and its structural reality, how do you see its role and responsibility in protecting academic freedom today? What structural changes or acts of institutional courage do you believe are necessary, if universities are to live up to their professed commitments to freedom and justice?

All universities in Australia are located on colonised and unceded Indigenous lands and some of these institutions, such as the University of Sydney, were established as colonial institutions by the British. So, the fact that universities in settler colonial states are deeply embedded within state structures of colonialism, dispossession and extraction is not an abstract idea – it is foundational to their very existence. For me, this context is crucial because it highlights how Western institutions and knowledge systems frequently reproduce systemic racial harm and its various intersections within higher education. In this context, many universities have failed the test of academic freedom on Palestine. As we have seen over the past 24 months, universities have banned peaceful protests, dismantled university encampments, removed anti-genocide posters, deployed cops on campus, and increasingly weaponised misconduct procedures to intimidate students and staff into silence. These restrictions have extended into the wider academic sphere. For instance, Palestinian scholarship has been pulled from academic journals and book publications across both mainstream and decolonial fields of scholarship for simply talking about Gaza.

Universities have all sorts of ways of curtailing academic freedom but conflation between psycho-social harm, on the one hand, and mere discomfort, on the other has had a particularly chilling effect on university staff. Lana Tatour and Andrew Brooks have outlined how Indigenous concepts of ‘cultural safety’ have been manipulated to deny Israel’s genocide and occupation of Palestinians. Randa Abdel-Fatah reveals that what is at stake is a ‘disarmament campaign’ to immobilise ‘our discursive and explanatory frameworks, our analysis and commentary, our slogans, protest language and chants’ with the aim of depriving the Palestinian solidarity movement ‘of its capacity to critique and resist Zionism and hold Israel to account’. The pro-Israel lobby, as Noam Peleg highlights, is working overtime to ‘dismantle academic freedom in defense of Zionism’ as part of a coordinated Zionist campaign that exerts pressure on universities and government to silence critical debate about Israel. In this context, broadly worded and vaguely defined notions of ‘safety’ have been abused or misused in the name of ‘protection’, while lending impunity to the worst crimes of state power including, genocide.

In the current climate of selective silence and repression, I see academic freedom as central to the university’s core functions of teaching and research, making the demand for a Palestine exception at odds with both the purpose of higher education and our ability to do our jobs. So, in short, yes, the gap between symbolic commitment to academic freedom and the structural reality of university governance could not be wider, which is why we must resist the illusion that universities will suddenly transform themselves into bastions of self-accountability. In my view, collectively organising against the corporatisation of the university and the racial investment it makes in colonial and extractive structures of power is necessary for structural change. As a start, universities must reckon with the ways they both reproduce racial and capitalist violence and simultaneously conceal associated traumas within their communities. There is also an urgent need for universities to move beyond selective framings of anti-racism that protect the privileged and comply with their own policies and procedures, especially as required by law. Crucially, they should ensure stronger protections for staff and students of colour within complaints processes.

In your view, what are the limits of ‘neutrality’ in academic institutions during a crisis of the scale of Gaza? What does it mean to refuse neutrality in this moment and what responsibilities come with that refusal, especially for educators and academics?

In my view, there is no such thing as a neutral position when a war of extermination is being waged against people living under relentless bombardment in an open-air prison without recourse to food, water, fuel or bread. Neutrality is at the heart of the Palestine exception, and a key institutional mechanism that normalises genocide and apartheid through silencing and censoring criticism of Israel and shielding it from accountability. In practice, neutrality is neither innocent nor impartial; it is complicity. We are not expected to be neutral on Ukraine or other cases of genocide – only on Palestine. Demands for neutrality trivialise the genocidal conditions in Gaza in ways that hide, minimise and normalise the dehumanisation of Palestinians. Neutrality is dangerous within the university context because it shapes and emboldens narratives to protect Zionists committing atrocities in Gaza and risks empowering white supremacy as a worldview within our classrooms. It is equally outrageous to expect Palestinian victims and survivors to articulate their pain and struggle in ways that provide comfort to the perpetrators responsible for their suffering.

In relation to responsibilities of academics and educators, everyone is responsible for stopping the genocide of Palestinians and for resisting the structural dehumanisation of Palestinians. I am firmly of the view that academics and educators must refuse demands for neutrality, meaning that we give neutrality no space. The responsibility of educators and academics in this moment is that we make a conscious choice to develop spaces of critical thinking in solidarity with Palestinians. Caution is needed around ‘safety’ discourse that is institutionalised, weaponised and manipulated in the service of Western geopolitical interests. In my view, safety loses meaning as protection when it relies on us looking away from the live-streamed extermination of Palestinians. This is especially so where it is deployed to deny Palestinians the right to narrate their own reality as victims and survivors of genocide, apartheid and belligerent occupation. A brave space is not a license to be bravely racist but rather is a space for educators, academics and students to advance human freedom and liberation, without exception [p. 50, 56]. This requires rethinking legal education as a site of anti-colonial praxis where teaching, scholarship and classroom engagement intentionally centre Palestinian narratives by making Gaza present in learning and teaching as an act of bearing witness and remembering, against forgetting.

In the wake of recent events, particularly after October 7 and the escalation in Gaza, did you feel a shift in how you were perceived or expected to behave as an academic with what is often described as Middle Eastern roots? Did these expectations shape how you navigated your public statements, teaching, or scholarly work? And how did they intersect with the unspoken pressures many academics of colour face when addressing politically sensitive or deeply personal topics?

This is an important question for revealing how the political maps onto, and structures, the personal and the communal. So, my response has several layers. In the West, the perception of Arabs and Muslims constantly shifts and is often contingent on our compliance and conformity with prevailing political discourse and geopolitical interests that often deny the very notion of the Palestinian and the Arab as human. I have observed that I am perceived as more ‘Arab’ in Western Europe than in Australia, and more ‘Arab’ at anti-genocide protests surrounded by cops than I am in my office at work. As a post 9/11 survivor of anti-Arab and anti-Muslim racism, I navigate these perceptions with an awareness of how universities comfortably inhabit colonial and orientalist assumptions about the Arab world and Arab communities. The last thing that universities want are Arab and pro-Palestine academics exercising political agency because it unsettles the military, political, economic discursive and geopolitical structures that uphold and maintain the power of the liberal state and liberal world order. For me, this is an important factor in understanding why universities are making it unsafe to criticise Israel’s genocide and apartheid regime.

White liberal norms structure many universities, and white spaces can be both brutally and blindly unaware of the privilege and racism they perpetuate. By whiteness, I am not referring to an individualistic concept, but a material structure tied to liberal institutions, power and ways of authorising and wielding authority through wilful or ignorant denial of racism and its intersections with geopolitics, gender, disability, capitalism and class. Navigating these white spaces in universities and other public institutions demands mental effort because our presence in these spaces as people of colour is conditional on making racialised oppressive structures unspeakable and on appealing to white spaces and discourses of power in our advocacy for institutional change. This reality places both a structural burden on Indigenous academics and academics of colour that is intensified in the context of naming or advocating for Palestinian lives within an already dehumanising environment that demands adherence to selective notions of safety and anti-racism. I have tried to advocate for Palestine and for our students within this dehumanising university environment, yet I also experience the compounding trauma of dehumanisation as an Arab academic of colour because my political and cultural identity is inseparable from the liberation of Palestine and from what it means to be an Arab in a world that refuses to see us as human.

With that context, yes, I did feel a shift. After 7 October and Israel’s escalation of violence in Gaza, my identity as an academic of colour became even more visible, scrutinised and racialised. Unspoken expectations formed around my wider activism on campus, especially as security ramped up. Following the NSW Premier’s decision to light the Sydney Opera House in the colours of the Israeli flag after the 7 October attacks, the state government issued warnings to universities, prompting increased security on various campuses. Cops and riot police became a recurring presence during crackdowns of anti-genocide protests on campus along with bans on certain chants. In the context of privileged and one-sided notions of ‘safety’, I observed students of colour, particularly Muslim students in hijabs being singled out with suspicion by university managers and police and treated as a threat to public safety.

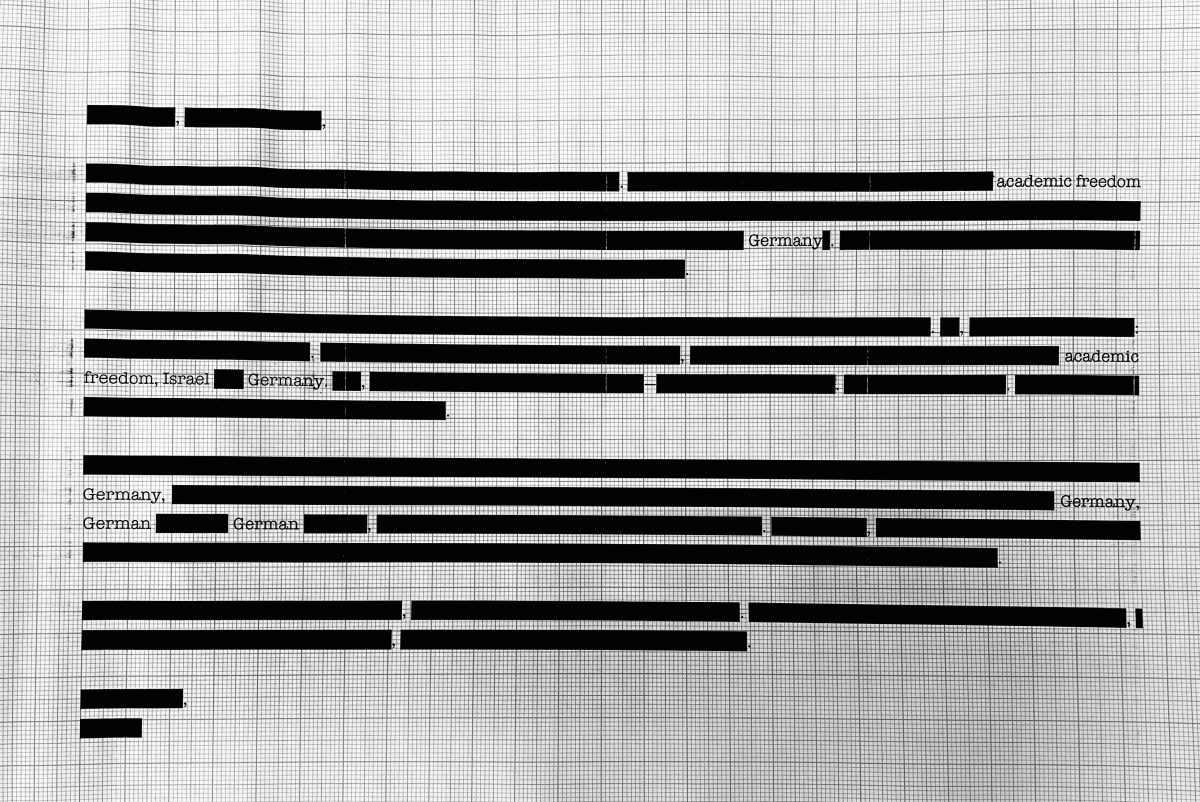

In general, there is an unspoken expectation that academics should choose their words carefully and soften what they say and publish, as it is likely to be under heightened scrutiny and the subject of a possible Zionist complaint. In Australia, we have seen how university complaints procedures have been deployed in other institutions to silence criticism of Israel and how academics have been threatened with loss of employment. Like others, I am expected to avoid certain words and topics when it comes to Palestine and to align my words with dominant and oppressive notions of ‘respect’ and ‘professionalism’ that require avoiding criticism of Israel, highlighting how structural precarity is produced by institutional racism and intensified by the Palestine exception. International law has been something of a protective shield but a limited one in an intense climate of repression and intimidation. As I write this, I am aware that this symposium for a German-based international law blog could potentially face censorship for highlighting Israel’s genocide of Palestinians. I would add that teaching international criminal law in this climate has felt extremely risky in a climate of genocide denialism. What Palestinians academics face is a more systematic and coordinated attack on their employment, funding, and scholarly opportunities, putting their existence within universities at risk, as the example of Randa Abdel-Fattah demonstrates.

This of course is part of a broader pattern aimed at silencing legitimate criticism of Israel. It is also part of the structural burden in which Palestinians, academics of colour and Indigenous academics, are expected to shoulder the emotional, political and intellectual labour of addressing difficult topics when we experience a lack of institutional safety ourselves as the default. These burdens are rarely acknowledged and often come at a personal and professional cost as structural precarity and workload pressures remain unchanged, even we when take on more pastoral care for student wellbeing. For many academics of colour, this dynamic is intensified when our scholarship, speech and teaching are policed to ensure we do not stray beyond what the institution deems safe or ‘respectful’. Sara Ahmed highlights that in talking about a problem, you become the problem [p. 63]. Critical scholars of race and colonialism and scholars who question and expose power face similar challenges when even conventional topics can be deemed a ‘safety’ issue. Walking into classrooms, carrying the crushing emotional load and profound grief of bearing witness to Israel’s mass killing and starvation of Palestinian children, families, doctors, nurses, students, academics, journalists and rescue workers has become all too familiar.

Since October 2023, Israeli military attacks on Gaza have not only resulted in immense civilian casualties, but also the widespread destruction of educational infrastructure: schools, universities, and libraries. The UN has reported that nearly all universities in Gaza have been rendered non-functional, and countless students, teachers, and academics have been killed or displaced. In this context, some scholars and observers have used the term ‘scholasticide’ to describe what appears to be the deliberate targeting of Palestinian knowledge systems, intellectual life, and future educational capacity. Do you see the destruction of Palestinian educational infrastructure in Gaza as a targeted attack on Palestinian intellectual and cultural continuity? How do you understand the relationship between physical violence and epistemic violence in this context—and what are the long-term implications of this destruction for Palestinian sovereignty, historical memory, and self-determination?

It is almost impossible to comprehend the scale of cultural destruction in Gaza. Palestinian cultural and educational institutions are not peripheral ¾ they are central to Palestinian knowledge, identity, memory and presence on the land. At stake is not only knowledge, but the right of Palestinians to self-determination. Palestinian knowledge, however, does not reside only in archives or institutions. It is embodied in the Palestinian people and their struggle. This is why Israel’s genocidal campaign is aimed not only at the destruction of cultural and educational infrastructure, but also at the people who carry, preserve, and transmit this knowledge.

The long-term consequences of such erasure are immense: an attack on historical memory and a profound assault on the conditions of Palestinian self-determination. Having lived in Palestine within Palestinian communities and worked with Palestinian civil society, I would never underestimate Palestinian perseverance and love of life and education as a source of freedom. It is unparalleled. They are rebuilders — and they will rebuild but the work of preserving Palestinian culture and knowledge cannot rest solely on Palestinians under siege and occupation. It is a responsibility that falls on all of us to host Palestinians, preserve and centre their writings, scholarship, and narratives, and create pathways and support for Palestinian students to continue their education outside Gaza. This may seem modest, but it is vital in terms of what we can contribute to the survival and continuing existence of Palestinian memory, history and culture.

Souheir, thank you for sharing your insights, your experiences, and your unwavering commitment to justice, critical pedagogy, and student wellbeing in these profoundly difficult times. The Palestine Project stands as a testament to what is possible when scholars refuse silence, challenge institutional complicity, and centre the lived realities of those most affected by global injustice.

Souheir Edelbi is a Lecturer at the Western Sydney University and one of the founders of the ‘Palestine Project’.

Khaled is working as a law clerk at the Higher Regional Court of Berlin. Prior to this, he worked as a research assistant at the Chair of European and International Law at the University of Potsdam. His research interests focus on international environmental law, the law of the sea, and the procedural law of international courts and tribunals. He is also a Managing Editor at Völkerrechtsblog.