The Encyclopaedic Value of the ICRC’s Customary IHL Study

Editor’s Note: This post is part of a symposium relating to the ICRC’s customary international humanitarian law study, featured across Articles of War and Völkerrechtsblog. The introductory post is available here. The symposium highlights presentations delivered at the young researchers’ workshop, Customary IHL: Revisiting the ICRC’s Study at 20, hosted by the Institute for International Peace and Security Law (University of Cologne) and the Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict (Ruhr University Bochum) on September 18-19, 2025.

Discussions following the publication of the ICRC Customary IHL Study (the Study) in 2005, have primarily focused on assessing the value of the Study as evidence of customary international law (CIL), or on the authority of the ICRC to codify/identify a list of customary international legal rules. CIL identification by non-State actors sits uncomfortably with doctrinal notions of CIL, where States remain the firm protagonists in its formation and identification. For this reason, the ICRC had been warned early on that its Study may be vulnerable to criticisms that it has overstepped the perceived boundaries of its mandate and the limited scope of activity allowed for non-State actors in the formation and identification of custom under classical international law (MacLaren and Schwendimann, p.1237). Indeed, it is likely that had the Study not been making a normative claim to custom already in its title, as Daniel Bethlehem (p.4) put it, many (but not all) of the doctrinal challenges the Study gives rise to would be alleviated.

In their introduction to the Study, the co-authors have stated explicitly that the Study was drafted primarily with legal practitioners in mind, ‘involved in the application, dissemination and enforcement of international humanitarian law’ (Vol. 1, p. xxxv; See also: Henckaerts). Nevertheless, without diminishing the significance of any debates on the relevance of the Study to formal applications of the law in a judicial or extra-judicial setting, where a positivist approach to law remains the paradigm, my argument is that this critique should not overlook the importance of the Study as a richly informative and insightful research tool. Thus, the present post examines the practical value of the study as an interdisciplinary research tool, before turning to a brief reflection on the relevance of the Study to questions of time, semantics, and legal culture, as well as international humanitarian law more broadly.

The Study as an Interdisciplinary Research Tool

According to the ICRC website, there are a total of 31 treaties and protocols which are of relevance to international humanitarian law today, and it is known that a considerable amount of the provisions of said treaties have now crystallised into CIL. Despite problems of enforcement, few would argue against the customary status of the most traditional rules of active warfare among them, such as the rules deriving from the principle of distinction. However, IHL is extremely detailed and highly technical. Not to mention the additional difficulties posed due to rapidly evolving military technologies and tactics, such as the use of cyberwarfare and artificial intelligence (ICRC resources). As such, the ICRC’s Study is a comprehensive resource from where a legal scholar can start untangling the thread of existing IHL rules, through the Study’s straightforward explanations (Volume I) and the accompanying resources identifying the practice (of States) (Volume II).

Furthermore, in my experience from an interdisciplinary perspective, I have observed that research relating to armed conflict is often fragmented among various neighbouring disciplines, such as law, international relations, sociology, anthropology and psychology. Thus, interdisciplinary research is helpful in appreciating the full scope and potential of the utility of the Study. On the one side, legal debates on the customary status of the rules enclosed help showcasing the complexity with which legal rules are analysed and scrutinised theoretically and in practice. On the other hand, the clear description and explanation make these highly technical and complex rules more accessible to researchers without legal or military training.

Therefore, the availability of the Study’s birds-eye view of international humanitarian law and its value as a resource in law and beyond, should ideally encourage the assumption of research projects on a broader scope of topics. These need not be rooted in law itself, but rather could open up the possibility of a broader interdisciplinary dialogue, which is essential for the promotion of the values and principles which humanitarianism—in its broad sense—aspires to promote.

Time, Perspective and Semantics

The dimension of time is ever-present in research concerning international armed conflicts (IACs) and non-international armed conflicts (NIACs), from a legal and a broader perspective. Depending on the exact research topic, time can be roughly categorised along the three dimensions of past, present and future: (i) the analysis of events that have already happened, which includes research for the purposes of formal proceedings before relevant bodies, (ii) the monitoring of developments during ongoing armed conflicts, and (iii) the estimation of future developments, be that in conflict management and resolution, questions of ius post bellum, or developments concerning the regulation of the use of evolving military technologies and tactics.

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to assume that focus on one of the three, completely excludes the relevance of the other two dimensions of time. This is because of the high complexity and the high politics (and the high emotions) that usually underpin any analysis concerning questions of ‘war and peace’, where interpretations of the past and the present intertwine as the determinants of an ever-uncertain future. As such, the past and the present are needed to inform future estimations.

Thus, research on ‘war and peace’ encloses in itself a deep engagement with the process of historicity, which in turn, characterises also the fluidity in the formation of customary international humanitarian law rules. Even though for clarity, legal literature speaks of the ‘shaping’ and the subsequent ‘recording’ of CIL by a relevant authority, it has also been argued that the process is in fact interconnected, within a ‘notoriously undisciplined and politically charged’ process (Hakimi, p. 148), following a ‘circular reasoning’ (Marcos) which directly challenges a linear understanding of time and legal evolution. Within that context, it could be argued that through its Study on the Customary IHL the ICRC did not take on itself the role of an authority declaring a list of 161 customary rules of IHL. Rather, as the core international organisation with expertise in IHL—the historical proponent and guardian of the Geneva Conventions—the ICRC has contributed to a far broader, ‘undisciplined and political’ discussion.

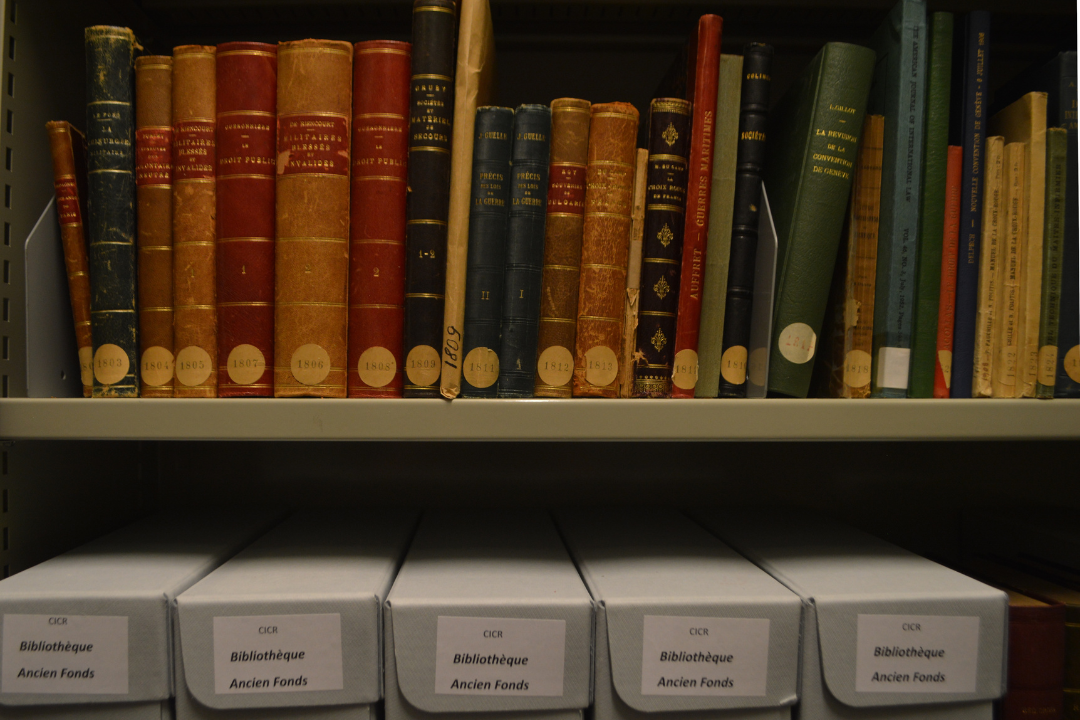

Customary law’s integral relationship with time, however, overlooks another aspect which may impact the law’s evolution, which is the evolution of language and the use of legal terminology in a mainstream context. The law does not function in a vacuum, and law’s neighbouring disciplines do not usually share the law’s need for coherent, strictly-defined and carefully-curated legal terminology. This is often a problem for lawyers dealing with questions of both ius in bello and ius ad bellum, where in a non-legal context a multiplicity of terms may be employed in order to allow for ‘wiggle room’ in the process of diplomatic negotiations (Klabbers, p. 505; For an e.g. in IHL see: Kornioti, Ch.1). Hence, as a ‘still photograph of reality’ of how Customary IHL stood in 2005 (Sandoz, ICRC Study Vol. 1, p. xxiii), the Study and its rich collection of materials on some of the most fundamental rules of IHL, carries an undeniable ‘encyclopaedic value’ which ought not be neglected.

By Way of Conclusion: A Turn to Legal Culture

To overcome the paradox of a simultaneous recording and shaping of customary law and to untangle the circular reasoning behind it, it has been observed that international lawyers need to overcome their usual inclination to think of CIL in terms of ‘finding already formed CIL rules’ (Marcos, p. 50). Legitimate expectations, it has been argued, form a metarule which in certain circumstances calls for States to act in a specific way based on Good Faith; itself a general principle of law and a source of law (Marcos, p.44-45). Legitimate expectations can, indeed, be a strong factor contributing to the formation of a customary rule of law. However, they are intrinsically related to the predominant legal culture at a given point in time.

International lawyers are usually uncomfortable with the differences across legal cultures, which challenge the universality of their discipline. Thus, it is comparative lawyers who usually investigate cultural differences, beyond questions of governance usually retained in the realm of international law (Kennedy). In that regard, it can be argued that the selection of materials that have been collected for the purposes of the Study serves as an entry point towards a deeper engagement with the legal cultures which shape customary IHL. Hence, it would have been beneficial, it is hereby suggested, to borrow from comparative law the practice of ‘distancing’ and ‘differencing’. Distancing, as a reflexive exercise concerning the positionality of the researcher, and differencing, as a recognition of the hermeneutical problem of interpretation (Frankenberg, pp. 70-72). Not in view of what is foreign, as analysed by Frankenberg, but with regard to the subtlety of context, which is not always readily available in legal practice.

For this process to be fully beneficial, IHL requires the construction of common spaces of dialogue between legal researchers and practicing lawyers, and between lawyers and experts from other relevant disciplines. The ICRC Customary IHL Study, as an encyclopaedic resource on IHL, holds the potential to open up such spaces.

Dr. Nadia Kornioti is an Associate Lecturer in International and Comparative Public Law at the Cyprus Campus of the University of Lancashire (UCLan Cyprus) and a qualified non-practicing Advocate in the Republic of Cyprus.