This is an English version of Vec’s original German article, translated by the editorial team with the author’s consent.

The title of Christoph Ransmayr’s novel, “The Last World,” fits the discovery of Franz Josef Land 150 years ago. An archipelago of some 200 islands, Franz Josef Land was discovered in the Arctic late in the summer of 1873. Its discoverers were the men of a multinational Austro-Hungarian North Pole expedition. When they set sail north from Bremerhaven in the summer of 1872, most of the world’s regions were already known, the oceans navigated, and their coasts charted. The imperialist era of taking possession of the completely unknown under international law was as good as over.

Image by Oona Räisänen on Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain).

But Franz Josef Land had yet to be sighted, its mountains surveyed, and its capes marked on the maps of polar explorers: take, for example, the northernmost point of Eurasia, Cape Fligely. The multinational crew of the “Admiral Tegetthoff” had not dared hope even for such a discovery. Their polar voyage had been marked by defeat and disappointment throughout. Their story has been recounted often, but never as impressively as by Austrian writer Christoph Ransmayr in his first novel: “Die Schrecken des Eises und der Finsternis” (“The Terrors of Ice and Darkness,” ‘TID’) was published in a small edition in 1984 and only became known to a larger audience when Ransmayr celebrated his breakthrough with “The Last World” in 1988. An English version of TID, translated by John E. Woods, was published in 1991 by George Weidenfeld & Nicholson Ltd and also by Grove Press New York (the following references to TID are to this American edition of the English translation).

A Breathtaking History of Discovery

As a young author, Ransmayr had approached the subject matter through reportage and travel. In these, he found a very unique tone and an idiosyncratic perspective. “Des Kaisers kalte Länder” (“The Emperor’s Cold Lands”), published in 1982 as a two-part reportage, was a first approach to that breathtaking story of discovery by the North Pole Expedition of 1872-1874. This story will be particularly remembered in Vienna in the summer of 2023, given that the voyage’s climax—the discovery of Franz Josef Land—occured exactly 150 years ago. The Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW) commemorated it from May 24 to July 14, 2023, in a small exhibition on its premises under the baroque ceiling fresco by Anton Hertzog: “Land, Land, endlich Land!” (“Land, Land, Land at Last!”). It too has its most impressive moments where the failures and coincidences become vivid; they have epic grandeur. It is no coincidence that Ransmayr already wrote of “a drama at the end of the world” (TID 16).

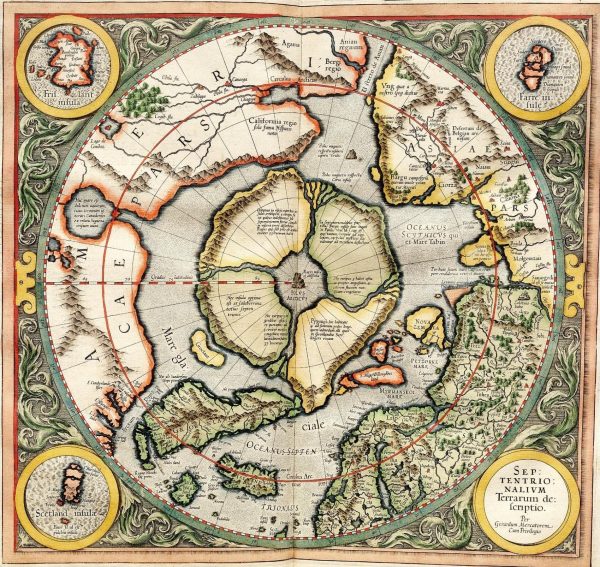

The expedition’s ship ran into ice fields much earlier than expected on its voyage to the Arctic. They first surrounded it as early as the end of July 1872. Then, in late August, the Tegethoff permanently froze stuck. The ice ruined any hope of reaching even higher latitudes: the ship, commanded by Carl Weyprecht as commander-at-sea, remained forever unable to maneuver. The mission of the Austro-Hungarian North Pole Expedition was to explore a northeast passage, but was also driven by the popular but fatal 19th-century Open Polar Sea theory. According to this theory, free waters could be found beyond the first ice fields further north, and there was the possibility of not only discovering new islands there, but also possibly reaching the pole by ship. Mercator visualized this notion on his 1595 map: ice-free waters and a magnetic mountain in the middle.

Gerhard Mercator, ‘Septentrionalium Terrarum descriptio’ (1595), via Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain).

The expedition payed for this mistaken belief; wintering on their sailing ship enclosed by pack ice and experienced the next great disappointment in the spring of 1873: because the ice drift had taken them further north, no clear sea opened up for them even as temperatures rose in the Arctic midsummer. In this bleak situation, the sudden appearance of a mountain range on the horizon on a fog-free afternoon of August 30, 1873, gave an unexpected sense of purpose. These peaks and lands were nowhere to be found on maps, and so the expedition was able to perform rituals of colonial ownership one last time and long after the age of great discoveries.

Of Creative Narratives and Legal Instruments

The history of international law in Franz Josef Land does not seem to have been told yet. Nor does it fit easily into the usual colonial histories. On the contrary, colleagues such as Rachael Lorna Johnstone, a lawyer working in Iceland and Greenland, have made it clear with their research that quite different narratives and instruments are at work here. While “plantation and possession” were usually at the center of legal theory legitimizing colonial seizure, other categories had to be used for the Arctic and Antarctic.

The emperor’s cold lands, such as Rudolf Island in Franz Josef Land, lie under an ice cap:

Photo by the European Space Agency via Wikimedia Commons (licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO).

Franz Josef Land is 85% glaciated, a record among Arctic countries. Just as in Antarctica, there was no plan for permanent settlement and use at the moment of discovery. However, in both cases there was no indigenous population to compete with for ownership. Who should own the lands? And should they belong to anyone at all?

In the Austro-Hungarian history of discovery, nationality and internationality are closely intertwined. This was a multinational expedition, with men from Germany, Hungary, Bohemia, Moravia, Italy, present-day Croatia and South Tyrol, but above all from present-day Austria. According to their self-image, they worked for the universal cause of science, and to this day, the international spirit of the Austro-Hungarian North Pole Expedition is emphasized again and again— having initiated, for example, the “International Polar Year” as a research tradition. At the same time, the North Pole Expedition was integrated into national patriotic and imperial contexts. When the men first set foot on the newly discovered land on November 1, 1873, after months of waiting—for at first the weather did not permit a hike to the mountains on the horizon—they performed classic rituals of seizure. They surveyed the new islands and named the topography after their Austro-Hungarian homeland. From then on the archipelago was called Franz-Josef-Land, there is a cape Wiener Neustadt, the island Klagenfurt near Wilczek Land, a cape Grillparzer, an Austria-Sund, Crown Prince Rudolf Land, etc. An Austro-Hungarian flag was also planted.

At the same time, interestingly enough, they refrained from taking legal possession in the name of the Dual Monarchy. Commander-on-land Julius von Payer wrote retrospectively:

“With proud excitement we planted the flag of Austria-Hungary for the first time in the far north; we were conscious of having carried it as far as our strength permitted. Even if it was not an act of necessity under international law and far from the significance of taking possession of a country, as it once was when Albuquerque or Van Diemen unfurled the insignia of their fatherland on foreign soil, we had nevertheless acquired … this piece of cold, rigid ground with no less difficulty.”

The country initially remained a no-man’s land; Austria-Hungary did not seek territorial sovereignty. This renunciation, however, did not prevent the public perception at home from pouncing on the proceeds of this expedition and the returnees with imperial and colonial enthusiasm. Their way back to Europe, however, was a painful one. They spent another polar winter in the belly of their ship, beset by dangerous ice pressures that could have crushed it, in catastrophic mental and physical condition, before leaving it behind the following May 1874. The mad plan: to walk across the ice until they would reach open sea again and the three heavy-laden whaling boats they carried could take them further south. The exertions were immeasurable, but the enterprise succeeded. Back home, commander-on-land Julius Payer immortalized the drama of the voyage on canvas. Leaving the ship for the south was staged as a religious-emotional climax: “Never back!”

Julius Payer, ‘Nie Zurück!’ (1892), via Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain).

At Novaya Zemlya, with unbelievable luck, they meet two Russian transporters who pick up the ragged men on the evening of August 24, 1874. The reception, especially in Vienna, was triumphant. In retrospect, at any rate, the reception of this discovery can be read as a form of Austrian polar colonialism.

Justifying Soviet Appropriation: Sector Theory and Legal Bricolage

An actual legal appropriation of the former no-man’s land was later carried out by the Soviet Union in the interwar period. On April 15, 1926, the government issued a decree, adopted by the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee:

“Are declared forming parts of the territory of the Union of Soviet Socialistic Republics all lands and islands already discovered, as well as those which are to be discovered in the future, which at the time of the moment of the publication of the present decree are not recognized by the Union of Soviet Socialistic Republics as the territory of any foreign state, and which lie in the Northern Frozen Ocean north of the coast of the Union of Soviet Socialistic Republics up to the North Pole, within the limits between the meridian longitude 32° 4’ 35’’ east of Greenwich … and the meridian longitude 168° 49’ 30’’, west of Greenwich …“.

The Soviet Union informed foreign powers, including Norway, about this decree. Thereupon, the Norwegian foreign minister declared that the territories lying in the so-called “Russian sector” would continue to be regarded by Norway as no-man’s land.

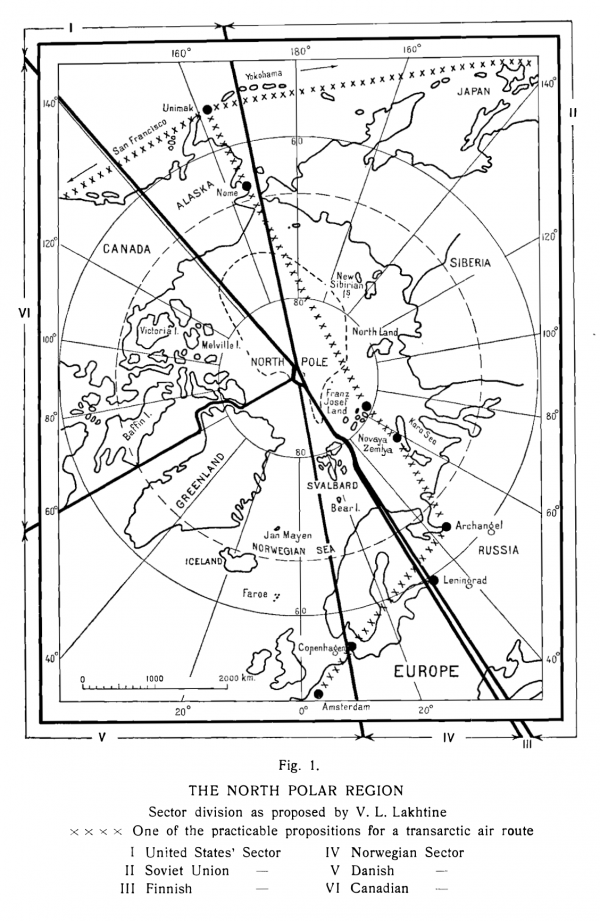

The so-called sector theory had been developed in 1907 by the Canadian senator Pascal Poirier as a legal argument to justify own Arctic land seizures or at any rate to ward off foreign claims. Decades later, Viktor Böhmert, an international law scholar from Kiel, defined it in an encyclopedia entry: “According to the sector principle, the land and sea areas near the pole within a spherical triangle, the corners of which are formed by the north or south pole and the eastern and western points of the mainland coasts of the states situated furthest north or south, are ipso facto to be subject to the territorial sovereignty or at least the right of appropriation of these states.” (Viktor Böhmert, Art. Sektorentheorie, in: Wörterbuch des Völkerrechts, 2nd ed. founded by Karl Strupp, edited by Hans-Juergen Schlochauer, vol. 3, Walter de Gruyter Berlin 1962, 248-250 [248]).

Later, with regard to Franz Josef Land, the Soviet Union still referred to actual acts of seizure, so that an accumulation of circumstances and bricolage of legal arguments is supposed to support its claim to appropriation. The sector theory, in any case, has been discussed by international law scholars in its borrowings from existing, accepted justifications, but has met with little response. Positive voices are to be found mostly on the part of Soviet authors (Leonid L. Breitfuß, Die territoriale Sektoreneinteilung der Arktis im Zusammenhang mit dem zu erwartenden transarktischen Luftverkehr, in: Petermanns geographische Mitteilungen, Heft 1/2, (1928), 74: 23-28). Today, for its part, it belongs to the history of international law.

You are entering the Soviet sector: the division of the Arctic sovietized many of the cold countries near the North Pole. The lush sector is labeled II at the upper right edge of the map. Image from Gustav Smedal, Acquisition of sovereignty over polar areas, 56.

However, all this could not prevent the islands’ sovietization. To this day, Franz Josef Land belongs to Russia, is designated by it as a restricted area, and in principle may not be entered. It has thus become a global-peripheral place of longing for travelers. As in other Arctic and Antarctic regions, sovereignty is claimed here by using environmental protection as a defensive argument. As Rachael Lorna Johnstone has argued in her interesting essay, this represents a reversal of traditional imperialist categories of the classical colonial period. Instead of de facto occupation, colonization, and, for example, agricultural use, the demonstrative renunciation of use under the banner of nature conservation is now part of the repertoire of actions used to keep other states from asserting claims.

Earth’s Mythical Periphery

Ransmayr used his narrative of the discovery of Franz Josef Land to create epistemic uncertainty. Two other strands run parallel to the historical story of the discovery in his novel, including a fictional adventure story whose protagonist has an insatiable longing for the North and wants to emulate the historical expedition from Svalbard. He is said to be a descendant of one of the participants of the 1872-74 expedition. We look over his shoulder as he organizes this journey, and author Ransmayr directs our gaze to his poetic disappearance into the vastness of the narrated Arctic: “I’ve often thought it uncanny how the beginning of every story, as well as the end, if you follow it far enough, gets lost at some point in the expanses of time […]” (TID 3). His fictional protagonist is also lost in the inhospitable icy wastes. It is a double whiteout, in which the snow of the north resembles the narrator’s white sheet and all certain contours blur.

We do not know whether we can trust the narrator Ransmayr. Facts and fictions are told side by side, they merge into each other. “Reality is divisible,” the beginning programatically states (TID 30): narrator Ransmayr intentionally fires up our uncertainty, is at least transparent in this intention, and in doing so pursues an anti-colonialist and enlightenment-critical project. The global hegemony claims of the Europeans, the exploitation associated with them and the victims of colonial policy are made clear: The 1984 novel criticizes, in the guise of a retelling of one of the most adventurous stories of discovery of all time, central axioms of European expeditionary striving and its ideology of expansion. It is a critique of civilization.

The ‘seizure’ of Franz-Josef-Land, whether it was actually connected to property claims or not, is part of a history of plundering that was based on a hunger for power and a desire for fame, and which equipped and legitimized itself with science. For the men of the historical expedition, things turned out just fine, with only one death to mourn. At the heart of his narrative, however, writer Ransmayr places another process of which even the critical history of international law still knows little: the appropriation and destruction of special places. Ransmayr’s Arctic becomes the mythic paradise of the narrator himself (TID 225-226). In the empty space of the Arctic, poetic indeterminacy and unavailability intertwine (Karin Schuchmann 10, 260, 266). The color photographs by the Austrian writer and filmmaker Rudi Palla (only contained in the German versions), provided with captions taken from the Book of Job, give Ransmayr’s narrative an Old Testament dimension.

It first obviously addresses the relationship to Arctic, elemental nature: “Hast thou entered into the treasures of the snow? Or hast thou seen the treasures of the hail?”(German edition of Die Schrecken des Eises und der Finsternis (SEF), 129, the King James Bible is used here for the English translation.) “Hast thou entered into the springs of the sea? Or hast thou walked in the search of the depth?” (SEF 137). “The stones of it are the place of sapphires: and it hath dust of gold. There is a path which no fowl knoweth, and which the vulture’s eye hath not seen.” (SEF 141). But they also reflect in their Old Testament language the bottomless abysmal dimension of this journey: “Have the gates of death been opened unto thee? or hast thou seen the doors of the shadow of death? Hast thou perceived the breadth of the earth?” (SEF 133). Here the adventure novel tips over into a moral-theological address against the background of the biblical forces of nature and asks questions whose addressee remains open. The reader, too, can relate them to themselves.

At the end, Ransmayr ponders how he as an author “stands in the midst of his paper seas,” and a nostalgia settles over his chronicle: through the historical material, he has appropriated facts and aesthetics of the distant land. Nevertheless, the ice-staring nature remains inaccessible for him as well as for us readers—and shines all the more beautifully as a place of longing.

Miloš Vec was appointed to a Chair in European Legal and Constitutional History at Vienna University in 2012. From 2016-2020 he was a Permanent Fellow at the Institut für die Wissenschaft vom Menschen (IWM), Vienna. He was also Fellow at the Wissenschaftskolleg (Berlin), Honorary Fellow at Historisches Kolleg (Munich), and Senior Hauser Fellow at NYU. Furthermore, he works as a Free-lance journalist, particularly for Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and is Editor of the Journal of the History of International Law.