The A Sud v. Italy Case after the KlimaSeniorinnen Judgment

Implications of the ECtHR’s Decision for Climate Litigation in Italy

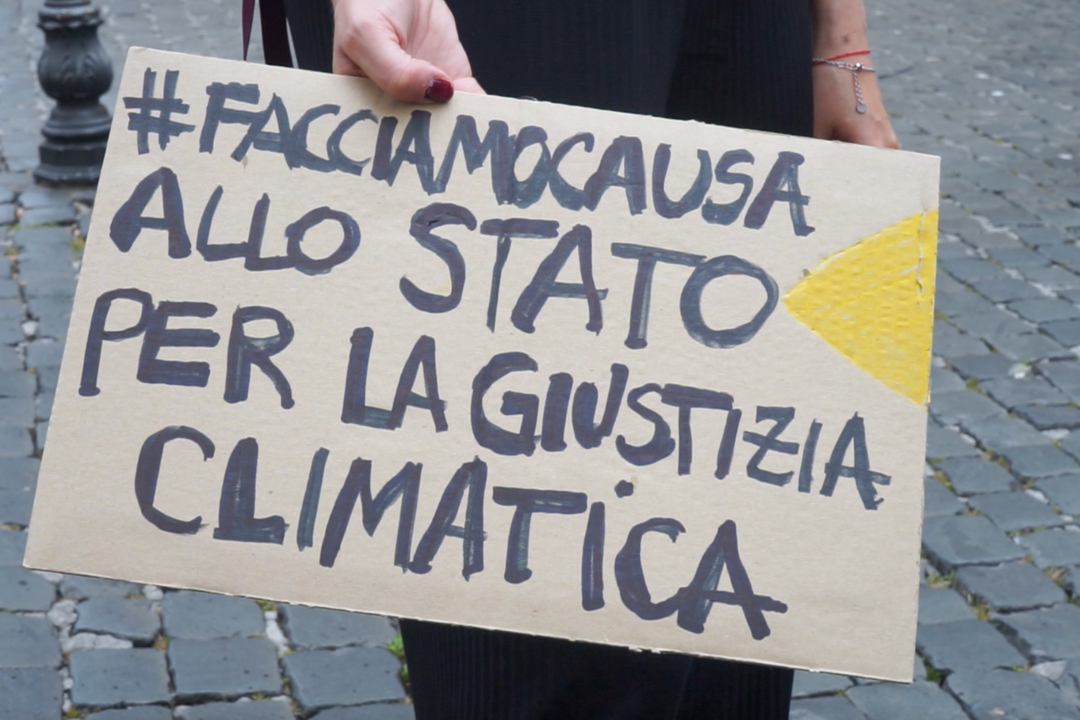

Just as climate litigation is on the rise globally, increasingly more climate cases are brought before Italian courts. On February 26, 2024, the Civil Tribunal of Rome has rendered its decision in the A Sud v. Italy case, also dubbed by its promoters as Giudizio Universale (Last Judgment) as part of a larger public campaign. The claim that Italy is violating a series of fundamental rights, including the right to a stable and safe climate, for its insufficient climate action was not decided upon by the Italian court that declared itself incompetent to hear this case. An appeal is in the making by the case proponents.

After briefly recapping the main points of the Italian judgment, this article discusses the relationship between this decision and another historic and most awaited judgment released by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) on April 9, 2024, in the Verein KlimaSeniorinnen Schweiz and Others v. Switzerland case. In line with the unanimous argument that this case will enormously influence climate litigation in Europe, this article aims to show how this cornerstone decision by the ECtHR can likely influence the fate of the appeal in A Sud v. Italy: The existence of a link between climate change and human rights and the two-tier margin of appreciation doctrine inaugurated by the ECtHR make the inadmissibility of the claim in the A Sud v. Italy decision highly questionable.

The Civil Tribunal’s Decision in A Sud v. Italy

The case was initiated by the Italian activist organization A Sud, which together with other associations and more than 180 individual claimants sued the Italian state before the Civil Tribunal of Rome for its alleged failure to promote adequate climate policies to respond to the climate crisis. This claim was based on the obligations deriving from the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement, some applicable EU provisions, articles 2 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), and some provisions of the Italian Civil Code on non-contractual liability.

The Tribunal held the case inadmissible. Its main argument was that the petitioners lacked a protected right or interest to found their claim, which is why the court held itself incompetent to judge on the merits of the case. In the view of the Tribunal, the Italian legal system lacks any protected right to the correct exercise of legislative power and therefore any legal position against which the Civil Tribunal could judge the adequacy of Italian climate policies. In relation to that, it considered the adequacy of climate policies a matter for the legislative power rather than for the judiciary. The Civil Tribunal therefore relied on the separation of powers to avoid jurisdiction. This is a well-established judicial argument, especially in cases where issues that have delicate societal trade-offs area at stake, like in climate litigation (Nollkaemper 2024). The Tribunal also adhered to another argument proposed by the defendants, namely that the Italian government cannot be deemed responsible for a multifactor phenomenon like climate change that is caused by the concomitant action or inaction of multiple States.

The A Sud v. Italy Decision in Light of Recent ECtHR Jurisprudence

The recent jurisprudence of the ECtHR is extremely relevant to evaluate the decision taken by the Italian Civil Tribunal, because the KlimaSeniorinnen decision and related case Duarte Agostinho and Others v. Portugal and Others dismantle exactly the arguments used by the Italian judge. These decisions are not directly applicable to Italy. However, they represent an authoritative precedent that clarifies the ECtHR’s standing on climate litigation for ECHR parties.

First, the KlimaSeniorinnen case relates to the Italian Tribunal’s argument that there is no protected justiciable position to entail a non-contractual liability of the Italian State. Curiously, the Italian Tribunal has not based its decision on the existence of a right to a stable and safe climate and other human rights invoked by the claimants, but on a presumed interest to a correct exercise of the legislative power that the court found inexistent. In the KlimaSeniorinnen case, however, the ECtHR establishes a clear link between the failure to adopt an adequate regulatory framework to pursue climate mitigation and the violation of human rights. In particular, the ECtHR found a violation of article 8 of the ECHR, which protects the right to private and family life. This is a right often invoked in environmental cases before the ECtHR that has been read in light of intergenerational equity arguments: Article 8 would be violated due to an excessive offloading of the emission reduction burden onto future generations (Sulyok 2024). In the future appeal to the A Sud decision, a recognized impact on human rights, as certified by the ECtHR, will certainly constitute a central argument to invalidate the conclusion of the first instance court, because the existence of a protected right constitutes a justiciable position that makes the A Sud claims admissible before Italian courts.

Second, in the KlimaSeniorinnen decision, the duty of Switzerland to protect the right to private and family life implies an obligation for the State to adopt a national framework to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The fact that a normative framework on mitigation must be in place makes climate change a matter of law and not merely of legislative policy (Nollkaemper 2024). In this respect, Switzerland had to pass a two-tier test (Sulyok 2024): A certain threshold of national action must be met to remain under the national margin of appreciation and not to incur in an infringement of the ECHR. In particular, five elements need to be verified in a comprehensive way (Bönnemann and Tigre 2024): whether the State has adopted targets to achieve climate neutrality within a measurable temporal timeframe, for instance in the form of a carbon budget; whether intermediate reduction targets have been agreed upon; whether compliance with these targets can be demonstrated; whether reduction targets are regularly updated; and whether legislative action has been adopted “in good time and in an appropriate and consistent manner” (para 550 KlimaSeniorinnen decision). Only if this threshold is met, States are free to enact specific climate solutions whose variability is not justiciable per se. This two-tier margin of appreciation doctrine therefore trumps the arguments about the division of powers utilized by the Italian court, because discretion is admissible only when certain conditions are met, and it is for courts to assess whether national climate actions are in line with the five elements mentioned above (para 412 KlimaSeniorinnen decision; Hilson 2024).

In addition, a legal approach to Italy’s duties in the field of environmental protection, and thus climate, would have been reasonable and legally justifiable also in light of the 2022 reform of the Italian Constitution. According to the amended article 9 of the Italian Constitution, “the Italian Republic protects the environment, biodiversity and ecosystems, also in the interest of future generation”. This fundamental principle not only justifies a duty to act on the part of the State to protect the environment, but can also favor an intergenerational reading of the rights protected in the Constitution, as happened in the Neubauer case before the German Bundesverfassungsgericht (Cittadino 2022).

Third, the implications of the Duarte Agostinho case, decided on the same day as KlimaSeniorinnen, teach us that, although climate change is a multi-causal and multi-actor complex phenomenon, the impacts of climate action or inaction on human rights can be traced back to individual States. The ECtHR has no jurisdiction for the extraterritorial effects of other States’ measures and that is why it dismisses the Duarte Agostinho application (in addition to the lack of exhaustion of national remedies when it comes to the court’s jurisdiction concerning Portugal). However, the ECtHR has jurisdiction over cases brought against individual States, as demonstrated in the KlimaSeniorinnen decision, which inter alia traces the complex context in which climate change related impacts must be assessed (paras 410-422). In this respect, the Italian Tribunal’s argument that climate change is a diffuse responsibility shows its limits.

It cannot be anticipated how the appeal in A Sud v. Italy will go. For instance, it is still to be seen how any appeal court or even the ECtHR (should the case reach it) would evaluate the two-tier margin of appreciation doctrine in the case of Italy. Will any court consider it sufficient to have EU regulations in place directly applicable to Italy (Hilson 2024) and thereby a sufficient domestic regulatory framework, as indirectly argued by the Civil Tribunal of Rome? Yet, Italy lacks a national coherent binding framework since mitigation targets are contained mainly in non-binding plans, such as the National Integrated Plan for Energy and Climate, that are nonetheless adopted in pursuance of EU climate law. In other words, does the implementation of EU regulations constitute a sufficient step to fall under the margin of appreciation, as defined by the ECtHR in KlimaSeniorinnen?

Conclusion

What emerges from the cases discussed in this contribution is that climate litigation prompts courts to revise the boundaries of existing legal categories to address a new and complex phenomenon with multiple implications like climate change. One example is the reformed reading of the margin of appreciation doctrine discussed above. Another example would be the new position of the ECtHR on the legal standing of associations while keeping a restrictive position on the legal standing of individuals.

What certainly the ECtHR teaches us is that the failure of States to reach the mitigation objectives they voluntarily agreed upon is an urgent matter of human rights protection and courts must have a say on it. The implication for Italy is that this direct link provides a firm basis for Italian courts to overcome the jurisdictional issues raised by the Civil Tribunal and concentrate on the merits of the case promoted by A Sud, and possibly to provide remedies.

Dr. Federica Cittadino (PhD, University of Trento 2017) is Senior Researcher at the Institute for Comparative Federalism of Eurac Research, Bolzano, Italy.