From Russia Without Law

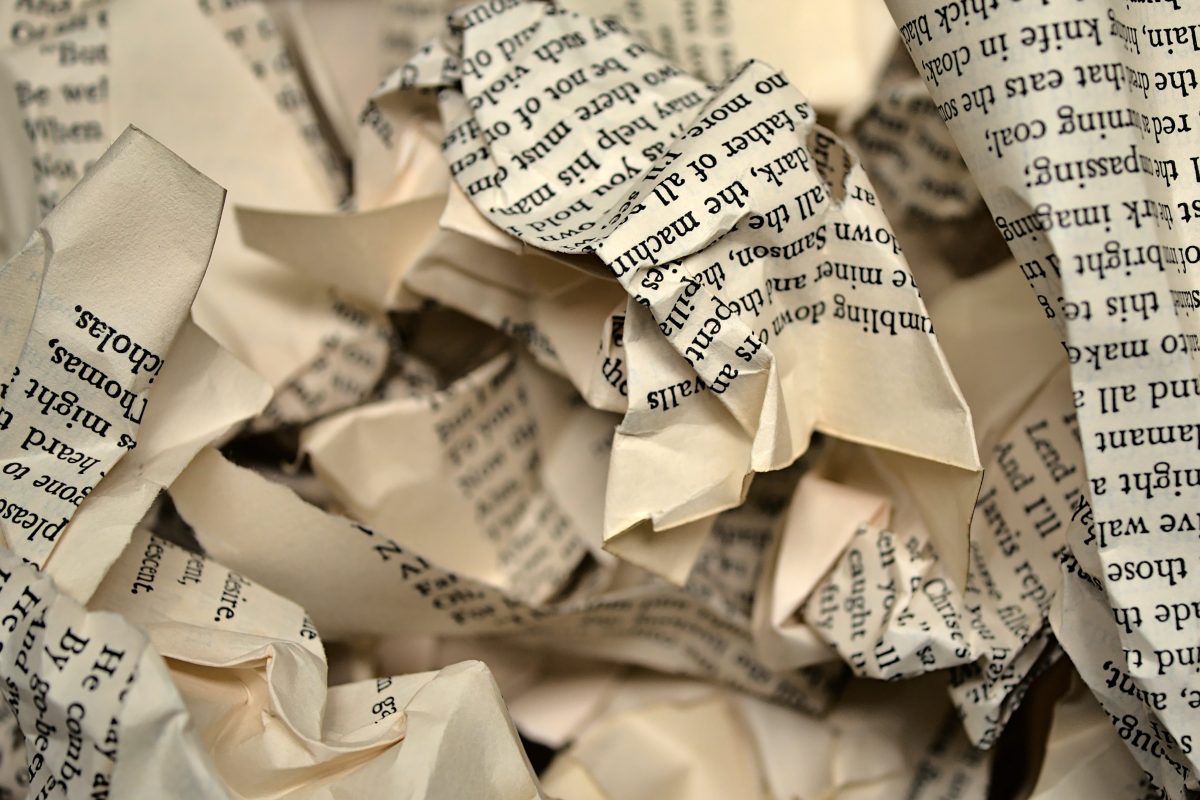

The Shredding of the Budapest Memorandum and its Significance for Future Security Guarantees

Effective security guarantees. That is what Ukraine proposed as a precondition for successful peace negotiations with the Russian Federation. The chief delegate emphasised that “the mistake that was once in the Budapest Memorandum” should not be repeated. The said document, officially known as the “Memorandum on Security Assurances in Connection with Ukraine’s Accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons” is a 1994 agreement in which Russia, the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US) made a number of commitments to Ukraine in exchange for the dismantling of Soviet-inherited Ukrainian nuclear weapons. Already in 2014, following the unlawful annexation of Crimea as well as Russia’s proxy war in the Donbas, Ukraine urged the UK and the US to live up to their obligations from the Memorandum. Western media outlets followed suit. The events preceding the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine triggered a similar outcry from Ukrainian officials However, a legal analysis of the agreement and the circumstances of its drafting show that it contains merely political assurances, and, that it is in fact Russia alone who continuously violates its provisions – with grave implications for the nuclear non-proliferation regime and potential future security pledges.

The Content of the Memorandum

The Budapest Memorandum consists of a preamble and six paragraphs. Notably, none of them contains any guarantees that would trigger a legal obligation for the signatories to intervene militarily to defend Ukraine’s territorial integrity.

In the first and second paragraphs of the Memorandum, the signatories restate their commitments from the UN Charter and the Helsinki Final Act. They pledge to refrain from the use of force against Ukraine’s territory, and to respect its independence, sovereignty, and existing borders. Every Russian attempt to revise the Ukrainian border, whether by an illegal referendum, or by force, constitutes grave violations of these provisions. Conversely, the UK and the US strongly condemned Russia’s actions in both 2014 and 2022 and thus acted in compliance with the Budapest Memorandum.

The third paragraph holds the parties to refrain from economic coercion designed to subordinate to their own interest Ukraine’s exercise of its sovereign rights. Since 2014, Russia has imposed embargoes on Ukrainian essential raw materials and agricultural products. The UK and the US did not engage in economic coercion against Ukraine.

Under paragraph 4, the signatories pledge to seek immediate UN Security Council action to provide assistance, should Ukraine “become a victim of an act of aggression or an object of a threat of aggression in which nuclear weapons are used.” The phrasing is somewhat ambiguous, as it is not clear whether the drafters referred to any act of aggression or specifically acts of nuclear aggression. Should the former be the case, Russia disregarded this obligation as well. This stands in stark contrast to the US, which, one day after Russia had commenced its invasion, intended to halt the offensive by means of a draft Security Council Resolution. The Resolution was not adopted due to Russia exercising its veto power.

But what if paragraph 4 of the Budapest Memorandum refers solely to threats of nuclear aggression? This reading is indeed preferable, given the interpretative guidance provided by subsequent practice of the signatories. In a recent Statement to the Conference on Disarmament a US Senior Advisor rephrased the commitment that security assurances provided to Non-Nuclear Weapon State Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (“NPT”) concern situations in which the States in question “are the victim of an act of, or an object of a threat of, aggression in which nuclear weapons are used.” Similarly, Russia reaffirmed that “[i]n the event of aggression involving the use of nuclear weapons or the threat of such aggression against a non-nuclear weapon State party to the NPT” it would seek the Security Council’s assistance. While Russian FM Lavrov’s staggering statement that the Memorandum “contains only one obligation – i.e., not to use nuclear weapons against Ukraine” is factually wrong in terms of the number of commitments, it nonetheless shows that all sides interpret paragraph 4 as referring to aggression and threats of nuclear capacity.

In this case, a situation as foreseen by paragraph 4 has not (yet) arisen. The Kremlin’s nuclear-related statements were carefully worded to still fall within the boundaries of Russia’s long-standing doctrine of nuclear deterrence. In its 1996 Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons (‘NW AO’), the ICJ acknowledged the policy of deterrence without pronouncing upon its legality. In this context, the Court explained what constitutes an illegal threat of force. In order for the declared readiness to use force to be lawful, the envisaged use of force must be lawful itself (NW AO, para. 47). The unanswered question whether nuclear arms could ever be used proportionately, for example “in an extreme circumstance of self-defence” in which a State’s “very survival would be at stake” (NW AO, para. 97) bears little relevance for paragraph 4 of the Memorandum, which requires a nuclear threat of “aggression”. As cynically as the words of President Putin and his henchmen resonate, a vague signalling of possible use of nuclear weapons in cases of extreme self-defence falls short of meeting the threshold of paragraph 4. Moreover, the communiqués are in line with international deterrence policies, including Russia’s own doctrine. The fifth paragraph reaffirms these deterrence practices and underscores the signatory States’ commitment not to use nuclear arms against non-nuclear weapon State parties of the NPT, except in cases of self-defence against armed attacks by such States in alliance with nuclear-weapon States. It comes as a relief that Russia did not violate this provision as well.

Finally, the parties are required to consult “in the event a situation arises that raises a question concerning the commitments” contained in the Budapest Memorandum. In 2014, Russian FM Lavrov did not attend the consultation meeting of the parties. In 2022, Ukraine again requested consultations under paragraph 6 of the Memorandum, shortly before Russia’s invasion – once again, to no avail.

A Relic of the Cold War

The Budapest Memorandum does not oblige its parties to intervene militarily in case of a breach. Even if the obligation to “respect the independence and sovereignty and the existing borders of Ukraine” could be interpreted as a duty to provide military aid to preserve or restore these borders, neither its object and purpose nor the travaux preparatoires would support such an understanding.

The Memorandum’s drafting history evidences that the agreement was never intended to serve as legal ground for military intervention. Quite the opposite – the UK and the US insisted on maintaining a merely political nature of their commitments. In response to a (largely unchanged) 1992 draft, the US Ambassador to Ukraine informed the Ukrainian MFA that the US would not commit itself to binding security guarantees. The US negotiators “took careful interest in the actual language, in order to keep the commitments of a political nature. US officials also continually used the term ‘assurances’ instead of ‘guarantees’, as the latter implied a deeper, even legally-binding commitment of the kind that the United States extended to its NATO allies.” UK representatives issued similar statements. The weakness of the Budapest Memorandum was apparent to all parties at the time – including Ukrainian officials – as well as to President Poroshenko in 2014 and President Zelensky in 2022, who both called for new legally binding instruments guaranteeing Ukraine’s security.

In the Memorandum’s preamble, the signatories welcome the accession of Ukraine to the NPT as a non-nuclear-weapon State, take into account Ukraine’s commitment to eliminate all nuclear weapons from its territory within a specified timeframe, and take note of the end of the Cold War and an accompanying spirit of disarmament. The desire to eliminate “leftover” nuclear weapons from post-Soviet territories before embarking on bilateral disarmament talks between the US and Russia was prevalent. Similarly, a letter, by which the signatory States introduced the Memorandum to the International Community focuses predominantly on nuclear disarmament and the shape of the world in a post-Cold War age. The purpose of the Memorandum thus concerns essentially non-proliferation matters, without any reference to binding security guarantees.

This poses the question why Ukraine signed such an ineffective agreement in the first place? Dismantling its nuclear arsenal in exchange for unenforceable political assurances and repetitions of existing principles of international law seems like a bad deal at first. However, scholars suggest that it was the maximum Ukraine could receive at the time: Ukraine’s Soviet-made nuclear weapons were not operational using the Ukrainian infrastructure and too costly to maintain, while Russia, the US and the UK were not ready to offer more. To Ukrainian President Kravchuk, signing the Memorandum seemed like the only option.

A Farewell to Arms?

Russia’s ongoing violations of the Memorandum and the weakness of the commitments contained therein herald grim times for the global non-proliferation regime and trust in security assurances in general. The unenforceable provisions of the Budapest Memorandum might incite States to seek protection in proliferation of nuclear arms, either by strengthening existing proliferation policies or by abandoning the path of non-proliferation. As evidenced by Ukraine today, States are more likely to seek stronger commitments to guarantee their security in the future. Likewise, if nuclear proliferators operating outside the NPT-framework are to dismantle their atomic arsenals, they will certainly ask for more in return than merely a contemporary incarnation of the Budapest Memorandum.

Ralf Lewandowski is a graduate of the University of Hamburg with a focus on European Law and Public International Law, and a Research Associate with the Complex Disputes team of Luther Rechtsanwaltsgesellschaft mbH in Hamburg.