The Gaza War Reconsidered

Future historians looking back upon the Israel-Gaza conflict may see that it stands at the nodal point of three major developments which have reshaped the coordinates of international institutions established in the wake of WW II. The first is the end of neo-liberal globalization and the emergence of protectionism and mercantilism among the major superpowers of the world – USA, Russia and China. The second is a weakening of multilateral human rights conventions and a trend to bilateral treaties or “deals”. The third is a new sovereigntist imagination of international relations that ignores international legal constraints and aspires to state impunity. These three intersecting developments are visible in the Israel-Gaza war and the international reactions to it. Understanding this should encourage us to formulate alternative visions.

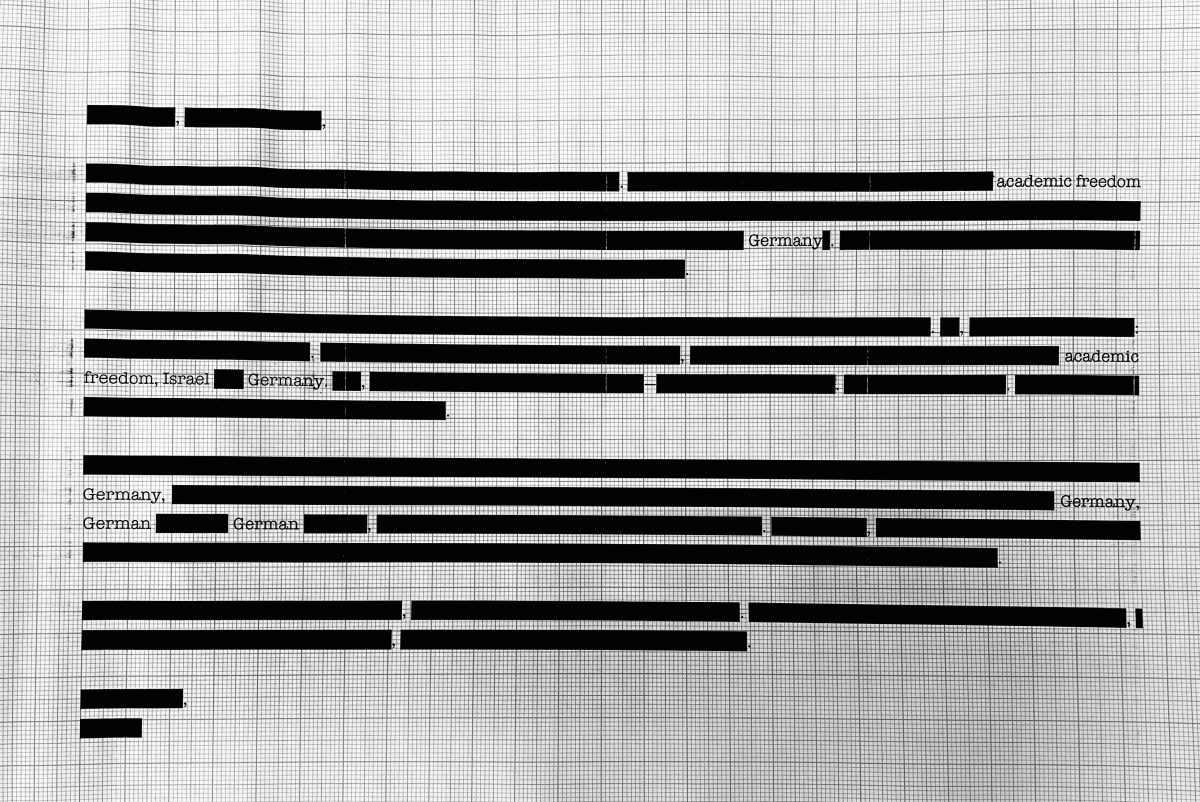

For academics, these shifts also have profound implications: they narrow the spaces in which universal rights discourses can be invoked, and they increasingly expose scholars who defend them to political pressure. In this sense, the Israel-Gaza war not only reveals the fragility of international law but also tests the boundaries of academic freedom, as critical inquiry itself risks being delegitimized.

On the first point: The current economic developments of a new protectionism and mercantilism are not limited to tariff wars or competitive subsidy policies. They carry with them a geo-politics, the dominant feature of which is to build new spheres of influence by brazenly annexing territory and/or threatening to do so. The logic is that control over land and resources is once again seen as essential to national power in a fragmenting global economy.

Russia has pursued this logic most explicitly. Its annexation of Crimea in 2014, the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, and the doctrine of Russkiy mir (‘the Russian world’) are framed as the recovery of ancestral lands but function geopolitically as a resource grab and a bid for strategic depth. In the United States, President Trump’s revival of territorial claims – floating the purchase of Greenland, musing about reasserting direct control over the Panama Canal, and even suggesting the annexation of Canada – reflects the reemergence of an imperial vocabulary that many assumed had been buried after 1945. China’s renewed sovereignty claims over Taiwan, despite the clear rejection of unification by the Taiwanese people, likewise signal a willingness to destabilize regional peace in order to consolidate national power and secure control over key maritime and technological routes. Israel’s de facto annexation of the West Bank, particularly in resource-rich Area C, fits into this same pattern. By fragmenting Palestinian territories and appropriating land, water, and mineral wealth, Israel entrenches a permanent imbalance of sovereignty under the guise of security.

These moves, though different in scale and context, share a common consequence: they erode the most fundamental norm of the post–World War II international order, namely the prohibition on the use of force to acquire territory. Enshrined in Article 2(4) of UN Charter, this prohibition was the cornerstone of an international system designed to prevent a return to the destructive logics of conquest and aggression that had devastated the first half of the twentieth century. This pattern also recalls earlier doctrines of Lebensraum (‘living space’), in which territorial conquest was justified as essential to national survival and prosperity. Although today’s powers frame their claims in the languages of security, sovereignty, or economic necessity, the underlying rationale is disturbingly similar: the normalization of expansionist policies that treat conquest as a legitimate path to strength in a competitive world order. Crucially, many of these projects carry an ethnonationalist intention – whether in Russia’s invocation of Russkiy mir, China’s narrative of cultural unity with Taiwan, or Israel’s drive toward a vision of Eretz Yisrael HaShlema (‘Greater Israel’). In the latter case, the entrenchment of settler sovereignty in the West Bank, especially in Area C, works in tandem with the constitutional redefinition of Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people, guaranteeing self-determination only for Jews. This combination of territorial expansion and ethnonational exclusivity echoes the way Lebensraum once fused conquest with a racialized and exclusionary vision of national identity.

On the second point: The rise of this new geo-politics has greatly damaged the multilateral human rights conventions in defense of universal civil and political, social, economic and cultural rights. Powerful states openly disregard international legal obligations and rhetorically downplay their significance. One of the most important post-WWII documents, the Refugee Convention of 1951 is being shredded to pieces not only by the racist and xenophobic regimes of the world but also by liberal democracies as they are busy compromising principles of refugee protection in order to accommodate the rise of ethno-national populism in their countries. The broader trend is toward bilateral agreements rather than multilateral conventions—or toward transactional “deals,” such as those promoted by President Trump in the realm of U.S. economic relations. This shift is underscored by the numbers: whereas the 1960s through the 1980s saw dozens of major multilateral conventions adopted across human rights, arms control, and environmental law—from the International Covenants on Human Rights (1966) to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (1968), the Biological Weapons Convention (1972), and the Law of the Sea Convention (1982)—the pace has dropped sharply since the 1990s. In the last fifteen years, no new universal human rights treaties and only a handful of global conventions of any kind have been concluded.

It is important to note that the Cold War era was itself marked by blockages, vetoes, and sharp East–West disagreements. Yet paradoxically, this bipolar rivalry created incentives for treaty-making: each bloc sought global legitimacy by sponsoring universal norms, while newly independent states of the Global South pushed hard for binding conventions as part of decolonization. This is why, despite intense ideological conflict, the Cold War decades produced a steady stream of multilateral agreements. By contrast, today’s world order is not characterized by productive rivalry but by systemic fragmentation. Major powers now tend to undermine institutions rather than compete to strengthen them: the United States has attacked or withdrawn from multilateral bodies, China prefers regional or bilateral arrangements it can dominate, Russia flouts international law while dismissing global norms as Western tools, and the European Union is weakened by internal populist pressures. The result is not occasional deadlock punctuated by breakthroughs, as during the Cold War, but a structural environment in which consensus itself has lost legitimacy, and institutions are not just paralyzed but actively delegitimized and defunded. Recent examples illustrate this erosion. Israel has relentlessly campaigned to delegitimize and defund UNRWA, the UN agency for Palestinian refugees, undermining the international consensus around refugee protection. Similarly, the United States has attacked and sanctioned the International Criminal Court, openly rejecting its authority whenever it threatens to investigate U.S. or allied conduct. These assaults on multilateral human rights institutions demonstrate not only a loss of consensus but an intentional weakening of the very mechanisms designed to prevent states from retreating into unilateralism, power politics, and impunity.

On the third point, and for the fate and future of Gaza’s most significant development, is the rise of a new autocratic and sovereigntist international order that undermines international law and transforms sovereignty into state impunity. Sovereignty, once imagined as a responsibility constrained by international norms, is increasingly asserted as an unlimited license to act without accountability. While Israel’s war against the people and territory of Gaza has energized international lawyers, and while South Africa’s case charging Israel with genocide in the International Court of Justice has awakened much respect and acclaim, the statement by the Court that a resolution of this case before the end of 2027 was unlikely has led to cynicism about the power of international law in general. Justice must not only be proclaimed but it must be done to be believed. The claim to impunity is most clearly visible in the behavior of powerful states that openly shield themselves and their allies from accountability. The United States has long refused to subject itself to the jurisdiction of the ICC, and it has extended this protection to Israel. Germany, too, has emerged as one of Israel’s most vocal defenders, providing arms and diplomatic cover even in the face of mounting evidence of a genocidal campaign unfolding in Gaza. Together, these acts of political protection demonstrate how international institutions are bent to the interests of a few powerful states, who claim exceptional status for themselves and their allies.

The coming together of these factors explains the passivity of the international community in permitting genocidal actions, crimes against humanity and war crimes to unfold in Gaza. No one seems to have the courage, conviction or power to defend the post WWII international regime anymore. And those who attempt to do so, such as South Africa in its ICJ case, pay a steep price: sanctions, diplomatic isolation, and the severing of political and economic ties with Israel’s powerful allies in the Global North. In this way, the costs of defending international law are increasingly borne by the few, while the many retreat into silence or complicity.

Hamas has also committed crimes against humanity through the mutilation and torture of innocent civilians, the abduction of children and the elderly as hostages, and the refusal to international organizations like the Red Cross to visit hostages. But more than seventy-five years after the adoption of the Genocide Convention by the UN, European leaders still prevaricate about the sale of weapons and materials to Israel, while Trump sets an example not only through his obscene statements about converting Gaza into a riviera for the rich but also through his own annexationist claims. The Israeli settlers, who cause havoc and destruction in the West Bank, have as their example the mightiest government in the international realm which has no respect for international law. Sovereignty has become impunity and equals the power of the strongest to trample the weakest.

For those like myself who believed that Israel had the right to defend its people against Hamas and its Jihadi allies after the brutal attacks of October 7, 2023, there came a point when after the killing of Yahya Sinwar on October 16, 2024, a compromise with Hamas, which would include the release of all Israeli hostages in exchange for Palestinian prisoners, would have been possible. After the first such exchange, the far-right ministers in Netanyahu’s coalition increased their pressure on him not to seek any compromise and to escalate the devastation of Gaza’s cities, hospitals, universities, mosques, and agricultural sites. The claim by the IDF that Hamas and its allies were hiding themselves as well the hostages in underground tunnels, in some cases built under hospitals, mosques and schools is probably true, but it rings hollow. For an army like the IDF that once used to pride itself on the ethical principle of using only “rubber bullets,” its actions in Gaza recapitulate the blindness of all imperial powers which in the process of chasing an elusive militia or guerrilla force only inflict disproportionate damage on the civilian population who then get even more mobilized against the occupying forces.

Israel’s claim that Hamas was not only hiding among the civilian population and institutions but that international aid organizations were also cooperating with Hamas, led to the defunding of UNRWA – one of the few organizations which since 1948 had the mandate to care for Palestinian refugees. The goal of the Israeli government is, and continues to be, that there should be no outside witnesses in Gaza – no international organizations, no independent journalists, no human rights monitors capable of documenting what is being done. This logic is brutally enforced. The very large number of journalists murdered by the Netanyahu government aims to create what Hannah Arendt has called “holes of oblivion,” to ensure that the memory of those who were killed will be erased because there will be no one left to tell their story. Yet the images of starving, maimed and wounded children of Gaza stare at us every day from many newspapers, social sites and television sets. There will always be someone who will survive to tell the story. In our tele-visual mediatic age, fake news will circulate but so will real news. Israel shares mistaken belief of all authoritarian regimes that they can manipulate truth forever. But, as the half a million Israelis who demonstrated the weekend of August 16-17, 2025 show, “you can fool some of the people some of the time but you cannot fool all of the people all of the time” (Abrahan Lincoln)! You cannot hide what is going on in Gaza from world public opinion nor from the Israel public. Israel, under the Netanyahu government, has become a “rogue state,” defying the laws of war, human rights law as well as humanitarian law and perpetrating genocide, whether in the full legal sense or not, against the people of Gaza by destroying them and their future as a group. What is beyond dispute, however, is that the destruction of Gaza is not only military but existential, aiming to erase the future of Palestinians in Gaza.

A future retrospective on the Israel–Gaza war may interpret it not only in light of the three major global developments already noted, but also as underscoring the urgent need for a new political imagination. At the same time, any such analysis would need to grapple with the extent to which the war has been embedded within structures of economic profit. According to the latest report by Francesa Albanese, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Occupied Palestinian Territories, titled “From Economy of Occupation to Economy of Genocide,” the Gaza war has led to a boom in the Israeli stock market. The Israeli weapons industry, and particularly, high-tech and AI-guided inventions such as exploding cell phones and pagers, used in Israel’s attack on Hezbollah, have become the envy of all autocrats in the world. With the cooperation of major tech organizations such as Palantir, Israel has now become a major player in the global AI-guided armament industry. Taken together, these developments suggest that the Israel–Gaza war is not only a geopolitical crisis but also a site where the entanglement of conflict, technology, and capital becomes starkly visible. The transformation of military violence into a driver of financial gain and technological prestige raises pressing questions about the trajectories of both global security and political imagination. If the conflict signals anything beyond immediate devastation and human plight, it is the urgency of confronting how war economies, particularly those underpinned by advanced technologies and transnational corporate alliances, shape the conditions of possibility for peace.

In this brief essay, I have purposefully stayed away from debates about history, about whether Israel is a colonial state; whether the Israeli-Palestine conflict can be understood in analogy to the French in Algeria; the Dutch and the British in South Africa or the latter in India. Such analogies have two objectionable consequences: first, they neglect the history of the Jews from Middle Eastern countries and other Asian countries (known as the Mizrahi) as well as neglecting the presence of Jewish communities in the Mediterranean region since the expulsion from Spain in 1492, known as the Sephardim. Second, the dominant Zionist fantasy of what was called “a land without a people for a people without a land,” (Israel Zangwill) is thereby given credence. There were Jewish communities in the Middle East and around the Mediterranean much before the start of Zionist efforts to buy land and settle Israel/Palestine. Today, when more than half of the population of Israel is of Mizrahi descent, many of whom originating from Arab speaking countries, it is important not to impose the paradigm of “western colonialism” upon their experience. Unlike the French in Algeria and the British in India, the majority of ordinary Israelis have nowhere else to go – despite the fact that a small well-connected and well-educated elite is leaving the country. The colonial paradigm has to be rethought and replaced by a paradigm of pluralist co-existence. The reactionary majoritarian resolution of the Knesset, which declared that Israel is the “land and country of the Jewish people alone,” denies the history as well as the present demographics of the land of Israel/Palestine, where two million Palestinian Arabs are also citizens.

It is time to silence the sounds of war and to heal the wounds of the children of Gaza and of all peoples in Israel/Palestine. Let our political imaginations soar: One state, two states, a confederation of sorts – international lawyers and political philosophers; refugee scholars and human rights experts will need to bring their good will and their imagination to bear upon the peoples of these lands who include Jews; Palestinians; Christians; Druze and Bedouin so that they can build a future together. Thus, academic freedom itself emerges as a crucial yet fragile resource. In a time when states seek to suppress dissent and delegitimize critical voices, universities and scholars are pressured to conform to nationalist orthodoxies or to silence themselves in fear of reprisals. Yet, academic freedom is indispensable for imagining alternatives to the current order: it sustains the rigorous critique of power, the documentation of atrocities, and the creative rethinking of political arrangements that might lead beyond cycles of war and domination. If academic spaces become complicit in reproducing state narratives or are captured by political orthodoxies, the possibility of generating the pluralist imagination that this region so urgently needs will be foreclosed. Protecting academic freedom is therefore not a marginal issue but a condition for envisioning and realizing a more just future.

The 19th century formula – one land, one people, one state – has been disastrous in this part of the world: ask the Armenian, the Kurds and the Alewites! We need a multi-national confederation where the Orthodox Jew can pray at the tomb of Abraham and the observant Muslim can enter Al-Aksa Mosque without the fear of being killed or chased out! A confederation means also self-government by peoples within a cooperative framework that would encompass shared air passage rights for international as well as domestic flights, sharing water and mineral resources and participating in joint environmental stewardship. In a part of the world that is particularly susceptible to climate change and desertification, the Israel-Gaza War has inflicted immeasurable damage upon these lands and has made vast terrains no longer cultivable. The task of the reconstruction of Gaza will require several decades at least.

The autocracies of the world have nothing to offer but death, destruction and future wars. While the political paradigm of lawless power and state impunity expands, its horrors are sending a message too. In this sense, ending this war via a concrete peace agreement, including the release of all Israeli hostages and certain Palestinian prisoners; the recognition of the self-determination rights of the people of Gaza and the West Bank via the declaration of a Palestinian state or some other political configuration, and the exchange and demilitarization of territories may signal the end of this awful global era we have entered.

Yet, such a political reorientation cannot succeed without defending the intellectual and moral conditions that make it imaginable. Chief among these is academic freedom: the freedom to produce knowledge, to critique state violence, and to articulate alternative futures without intimidation or sanction. As human rights norms erode and sovereigntist impunity spreads, academic freedom becomes both more endangered and more essential. The ability of scholars, journalists, and cultural workers to document atrocities, contest propaganda, and preserve memory is a necessary counterweight to regimes that seek to monopolize truth. If peace is to be more than a fragile truce, it must rest not only on territorial compromise but on the protection of those civic and intellectual freedoms that allow societies to imagine justice, and to resist the erasure of peoples, histories, and rights.

Seyla Benhabib is a senior research scholar and adjunct professor of law at Columbia Law School.

Summary: After noticing her open letter didn’t age well, prof. Benhabib thinks the genocide was justified ONLY for the first year.

History remembers, the internet does too.