Testimonial Oppression in Palestine

Assessing Institutional Complicity and Practices of Silencing

How is silence rendered a tool of violence? Kristie Dotson’s work on Epistemic Violence provides critical insights into the practices of testimonial oppression, particularly silencing and smothering, that produce epistemic harm against marginalized groups. Dotson highlights the systemic strategies used to suppress the voices of oppressed natives, distort their narratives, and deny them epistemic agency. Her framework is especially relevant to the ongoing situation in Gaza, where multiple forms of silencing are observable within international institutions, academia, Western media, and other platforms. This blog post reflects, through Dotson’s framework, on the mechanisms of silencing within international organizations and Western media, which have contributed to the dehumanization of Palestinians, the marginalization of their voices, and the obstruction of their demands for justice and accountability over the past two years. While the strategies of silencing discussed here are not exhaustive, this post aims to offer scholars new conceptual tools to identify, analyze, and address epistemic violence perpetuated in colonial settings and its role in undermining legal accountability.

Epistemic Violence and Practices of Silencing

Dotson identifies epistemic violence as “a refusal, intentional or unintentional, of an audience to communicatively reciprocate a linguistic exchange owing to pernicious ignorance” (p. 238). The harm resulting from this reliable ignorance is context-dependent and requires an analysis of the existing power dynamics that create harmful ignorance in a specific context. Dotson refers to this form of reliable ignorance as pernicious ignorance. Epistemic violence thus functions through the failure of an audience to communicate, engage in, and reciprocate —whether intentionally or unintentionally — linguistic exchanges allowing hearers to understand the vulnerabilities of the oppressed communities. Yet, a successful interaction between the speaker and the hearer necessitates a form of reciprocity, where they recognize and acknowledge each other’s speech to form a “successful linguistic exchange” (p. 237). In fact, the speaker cannot force the hearer to listen, and subsequently accept the speaker’s testimonies to fulfill the requirement of reciprocity and ensure a successful linguistic exchange. While “we all need an audience willing and capable of hearing us,” the level of denial of this reciprocal communication to “entire populations of people” constitute epistemic violence (p. 238).

Dotson then identifies two practices of silencing and testimonial oppression: testimonial quieting and testimonial smothering. Testimonial quieting occurs when the hearer fails or refuses to acknowledge the speaker as a “knower,” meaning that the speakers lack credibility to deliver testimonies about their own lived experiences. Testimonies are therefore dismissed as part of an “active practice of unknowing” (p. 243) that is based on stereotypes and colonial erasure of the native voices.

The second form of testimonial oppression, testimonial smothering, refers to the practice of omitting and changing one’s testimony to appeal to the audience’s testimonial competence. To accommodate to the audience’s limited knowledge, the speaker resorts to smothering their own testimonies. Dotson considers this form of smothering as “coerced silencing” that pushes the speaker to engage in “self-silencing” practices (p. 244). This practice may occur when a speaker avoids using terms, such as “genocide” and “massacres”, to describe the Israel’s conduct towards the Gazan population, when certain audiences (e.g., Germans) do not accept such labels in view of the historical context and generational guilt present in such contexts. The discomfort of such audiences became evident during an interview conducted by German journalist Jasmin Kosubek with Professor John Mearsheimer, in which she expressed her unease, as a German, with hearing terms like “genocide” and “apartheid” used in the context of Palestine.

In the context of Gaza and Palestine, it is essential to critically assess the linguistic exchanges that shape global discourse and the extent to which they deny reciprocal communication. As academics, we must interrogate the colonial and power structures that systematically devoice Palestinians, deny them agency, and silence their testimonies. These dynamics actively shape historical narratives by legitimizing certain accounts while marginalizing and delegitimizing the voices of oppressed populations. Situating such practices of silencing within broader frameworks of power reveals them not merely as acts of omission, but as deliberate attempts to reshape historical memory, distort facts, and obstruct pathways to justice and reconciliation.

Institutional Silencing: Media

This section highlights the different practices of silencing employed to control the global narrative on Palestine at three different levels: media, academia, and law. In this respect, testimonial quieting has been a common practice in international media when dealing with the context of Gaza. Since 07 October 2023, Israel has banned international media from entering Gaza, effectively preventing external reporting on the ongoing humanitarian catastrophe. As a result, the only consistent and direct source of information has been Gazan journalists who have been risking their lives for over two years to bring the truth to light. Since the start of its military campaign in October 2023, Israel has — thus far — killed over 210 Gazan journalists. Despite their immense risk and the harrowing documentation they continue to provide, many international actors, including the UN, have failed to treat their testimonies as fully legitimate in the absence of corroborating international media presence. The UN Secretary General, António Guterres, claimed that the ban on international media in Gaza “suffocates the truth”, given that “so many stories remain untold”. Yet, this raises troubling questions: haven’t Palestinian journalists been telling and sharing the truth all along? Haven’t they, at great personal cost — often at the expense of their own lives and families — been bearing witness to the devastation? In the face of international media ban, Palestinian journalists have shouldered the full burden of reporting from what has become one of “the deadliest places” to report from. By implying that truth remains hidden without international media, the UN Secretary General’s statement undermines the credibility and value of voices of Palestinian journalists, suggesting that their stories are incomplete or insufficient without Western validation.

While the ban on international media entry into Gaza is rightly condemnable — a blatant violation of press freedom — it is equally dehumanizing and racist to treat the reporting of Palestinian journalists as lacking credibility or completeness. Such a stance silences the native voice, denies Palestinians their agency, and renders their testimonies secondary to those of their international, non-Palestinian counterparts. In this regard, Abubaker Abed, a Gazan journalist, powerfully states:

“So, it’s completely enraging and unacceptable, because we are like — again, we are like any other reporters, media workers and journalists across the globe, and we have the right to be given the access to all media equipment, the access to the world, and our voices must be amplified, because, again, we don’t have any party to this war”.

Abed’s words highlight the double standards that often prevail in coverage of Palestine, where the voices of Palestinian journalists are not only undervalued but actively sidelined. This marginalization reflects a broader pattern of epistemic injustice, in which native testimony is dismissed unless validated by external, often Western, institutions. This form of testimonial quieting is evident for both Palestinian individuals and institutions alike. Even when reporting their own deaths, Palestinian institutions were deemed unreliable sources of information for the international Western audience.

Since October 2023, many international media platforms labeled the Palestinian Health Ministry in Gaza as a ‘Hamas-run Health Ministry’ in an attempt to discredit casualty reporting and treat it as a form of propaganda, despite major human rights organizations and the UN affirming that the numbers reported by the Gazan Health Ministry have been accurate. In an interview with Le Monde, the spokesperson for the Office for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights confirmed that it has been working with the Health Ministry for years and considers it a reliable source. In a separate statement, Human Rights Watch (HRW) also affirmed the credibility of the figures reported by the ministry.

In addition to testimonial quieting, Palestinians often find themselves in positions where they have to resort to smothering to share their narrative with the world. Given the systemic online censorship of Palestine-related content on Meta platforms, Palestinians and others talking about Palestine have to change and edit their language to avoid being flagged and censored. The Arab Center for the Advancement of Social Media reported that the Palestinian youth has resorted to self-censoring and deleting many of their statements on social media out of fear.

Whereas testimonial smothering refers to the act of the speaker adjusting their speech to appeal to the hearer. There have been documented attempts of media platforms purposely smothering or manipulating the speech of Palestinians in order to appeal to a particular audience by taking advantage of language and translation barriers. The BBC has famously mistranslated the testimony of a released Palestinian prisoner in order to paint a specific picture of arbitrarily detained Palestinians as ‘Hamas sympathizers’ instead of considering them hostages worthy of global sympathy and solidarity. In this interview, the BBC purposely mistranslated the testimony of the detainee, claiming that she expressed support and love for Hamas. Hamas was not even mentioned once by the detainee during the interview. Thus, mistranslation may be added as a form of testimonial oppression and part of epistemic violence.

The ICC and Testimonial Silencing

In November 2024, the ICC Pre-trial Chamber released arrest warrants against Israeli and Palestinian figures: Benjamin Netanyahu, Yoav Gallant, and Mohammed El Deif. While the list of accusations for the late Hamas leader, El Deif, includes “rape and other forms of sexual violence,” the list of accusations for Netanyahu and Gallant does not refer to sexual violence as part of the charges. This denial comes after multiple reports, including by UN agencies, that documented sexual violence perpetrated by Israeli soldiers against Palestinians. On May 2024, UNRWA documented and reported on testimonies of Palestinian men and women that could “amount to sexual violence”. Similar reports were shared by Israeli organizations such as The Association of Rape Crisis Centers in Israel and B’tselem regarding the sexual abuse and torture in Israeli detention facilities. In addition to documented testimonies, a leaked footage at Sde Teiman detention camp showed 12 Israeli soldiers raping a Palestinian prisoner. Despite the existing evidence and testimonies of Palestinians regarding perpetrated sexual violence, the ICC did not address these allegations in the list of charges against Netanyahu and Gallant. While the reasoning behind this omission likely stems from institutional politics, it is worth highlighting the narrative of exclusion used here by the ICC as a silencing tool that further undermines Palestinian voices and discourses. Moreover, such language might have a direct impact on the courses of justice and accountability that we are yet to witness as proceedings continue.

To note that this was not the first instance when the ICC has engaged in testimonial silencing. During his visit to the Rafah crossing on 29 October 2023, Prosecutor Karim A.A. Khan made a statement that showed a disturbing asymmetry between Palestinian and Israeli narratives. To describe Israeli testimonies, Khan refers to the “horror [of] the pictures emerging from Israel on the 7th of October” and the gruesome details of the attacks. He mentions the “burnings and executions and rapes and killings” of Israelis while acknowledging “the hatred and the cruelty that underpinned those attacks.” As for the Palestinian framing of events, Khan considers Palestinian victims “as caught up in hostilities” and “dying” in a war that they do not want to be part of. While he describes “the bodies of young children […] being dragged, baked in dust, still and silent,” he subsequently praises the very same resources that led to their killing as he considers that the Israeli army has “a system that is intended to ensure their compliance with international humanitarian law” and well-trained lawyers “advising targeting decisions”. Palestinian victimhood is thus contextualized as a mere incident of war; there is no “cruelty” nor “hatred” behind their killing as such framing is only applied to the other’s suffering. While recalling that ICC prosecutors should uphold principles of independence and impartiality in their work, such statements by an ICC prosecutor, in their capacity as an international civil servant, illustrate how testimonial silencing operates within the international legal arenas by enabling and embracing differentiated and asymmetrical narratives as part of official statements.

Conclusion

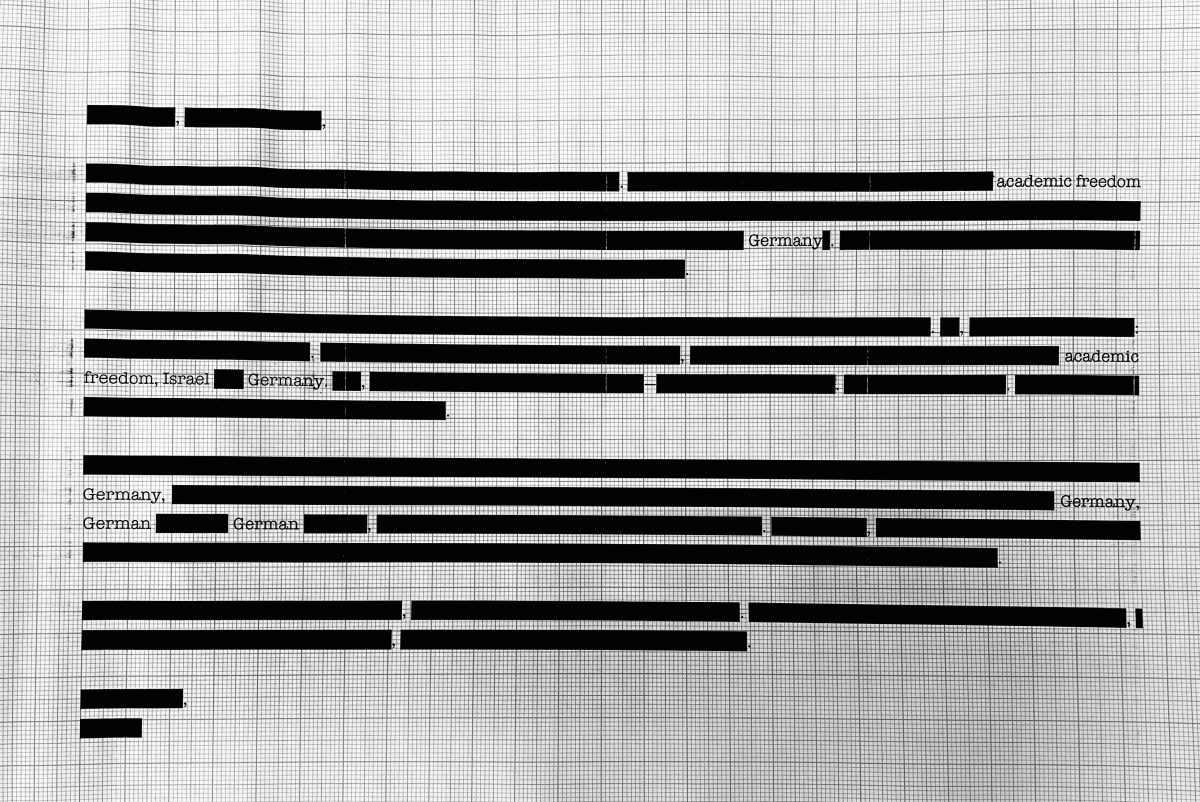

By reflecting on Dotson’s framework, this post engages with the conceptual tools of silencing to diagnose and examine epistemic violence during the ongoing military campaign of Israel in Gaza. It is a preliminary assessment of limited and specific discourses that were employed within Western media and international institutions to sideline and oppress Palestinian narratives. Further research is needed to empirically examine other instances of epistemic violence, including in academia where the “Palestine exception” prevails. As shown in this blog, using categories of silencing allows researchers to identify and challenge silencing as a mechanism of oppression that sustains colonial relations and undermines legal accountability.

The author chose not to disclose their full identity due to concerns over potential persecution.