Say My Name: Legal Silence That Speaks on the Ongoing Nakba in Palestine

A Reckoning for International Law’s Complicity

International law (IL) remains complicit in its omissions, not only through what it permits, but through what it refuses to name. Nowhere is this more evident than in its persistent failure to apprehend the Palestinian condition, which can be defined as the “Nakba”(Arabic for catastrophe), as an enduring structure of violence. I foreground one of the Nakba’s symptoms as the erasure of settler colonialism from legal recognition, which has been repeatedly relegated to historical discourse. Dominant juridical vocabularies, conflict, occupation, apartheid, genocide, fragment this structural violence into discrete, palatable forms, enabling legal discourse to orbit around, rather than confront the underlying logic of elimination. Nowhere does this insecurity of the field surface more sharply than in the case of Palestine, exposing IL‘s colonial inheritance and continuing entanglements. Even as global discourse on Palestine has shifted from humanitarianism to criminal accountability for victims, it remains tethered to vocabularies that litigate symptoms and consequences while ignoring structure.

This article contends that the ongoing Nakba is foundational to any meaningful legal analysis of Palestine. Drawing on critical scholarship, it interrogates the legal profession’s structural evasions and asks what it means to center this lived reality in times of live-streamed atrocities and academic denial.

Legal Histories of Complicity

IL has structured and sustained colonization in Palestine. Foundational legal instruments, from the 1884 Berlin Conference, codifying imperial partition under the guise of “civilization” (pp. 147ff.) to the Balfour Declaration, codified into the League of Nations Mandate system (pp. 39ff.), normalized racialized sovereignty, entrenched European colonial governance (p. 513f.) in Palestine, and juridically enabled Zionist settler colonization as a project of imperial delegation (p. 113). Early Zionist movements absorbed European models of nationalism and colonial ideology, ultimately resulting in what Veracini calls the post-Balfour “surrogate” colonization of Palestine (p. 62). The 1947 UN Partition Plan continued this logic, repackaging structural dispossession as neutral diplomacy.

Even the post-1945 legal order, despite rejecting classical colonialism (pp. 151ff.), failed to address settler colonies as a legal category. That said, the myth of conflict resolution has to be disrupted in order to center the logic of dispossession. Engaging Palestine through this lens necessitates a rupture with the 1993 Oslo accords (pp. 342ff.), which obscured power asymmetries by a false framing of negotiation between equals, institutionalized the Palestinian Authority as nominal “self-government,” and entrenched “indefinite occupation, statelessness, and fragmentation” (pp. 4-5) through an architecture that stratifies Palestinian existence into differentiated regimes of control.

The 1948 Nakba, therefore often mistaken as mere historical rupture, inaugurated a continuing structure of systematic dispossession, village destruction, and the mass expulsion of over 750,000 Palestinians (pp. 9f.). As the denied right of return still endures across generations, the Nakba is rendered an ongoing reality.

Legal Architecture of Settler Colonialism

The conceptualization of settler colonialism, which emerged from Australia, was famously crystallized by Patrick Wolfe, who defined it as a sustained structure (p. 2), not a simple form of genocide (p. 390): one that “destroys to replace” (p.388). Wolfe’s concept of “structural genocide” (p. 403) resists narrow definitions of genocide as mass killing as besides direct violence, elimination within settler colonialism includes displacement, assimilation, renaming, and biocultural erasure. Yet IL’s core instruments, such as the prohibition of forcible population transfer by an occupying power grounded in customary law, reaffirmed in the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 (Article 49), or the Genocide Convention, fail to capture this. Hence, Wolfe warned, “the genocide tribunal is the wrong court” (p. 404). A Settler Colonialism Convention could codify it as a sui generis crime, paralleling Apartheid, centering structural violence, land expropriation, denial of Indigenous self-determination and legalized discrimination, while enshrining redress, return and reparation as central to decolonization and addressing third-party complicity. Genocide’s elevation to the apex of ICL stems from post-Holocaust moral consensus (pp.609ff.) and its depoliticized legal framing focuses narrowly on group destruction rather than structural domination. In contrast, apartheid, while recognized in the 1973 Convention and Rome Statute, remains marginalized due to its explicit critique of racialized state power (pp.1148ff.) and inescapable association with indigenous decolonization struggles.

This divergence reveals IL’s preference for episodic crimes over the ones exposing structural domination, though apartheid and genocide are not always distinct: when settler colonial regimes impose conditions intended to destroy Indigenous groups, they may straddle both legal definitions. Yet settler colonialism exceeds both categories. As such, subsuming it under existing categories like crimes against humanity only risks repeating apartheid’s marginalization. However, scholars caution (pp. 340ff.) that the political reality of norm-setting is skewed against transformative instruments, while the international legal order remains structurally resistant and reliant on settler states’ political will (pp.11ff.).

Settler colonialism also operates as a logic of governance (p. 147), institutionalized through law. Zionist colonization, explicitly framed as a settler project since the 19th century by using “transfer” as its “logic of elimination” [as Herzl and others imagined territorial acquisition through substitution and erasure (p. 38)], predates the 1948 Nakba. In Palestine, this logic manifests through systematic demographic engineering, territorial fragmentation, legal interpretations of “transfer”, which in turn, produced statelessness (pp. 35ff.) visible in settlement expansion, the apartheid wall, Gaza’s blockade, racialized land laws within Israel, and most recently, imposed famine. This article, however, does not debate whether Israel is a settler colonial state. Scholars like Rodinson, Shafir, Yuval-Davis, among others have historicized this trajectory, while Palestinian thinkers like Dana and Jarbawi, Sayigh, Shehadeh, Zureik, Said or Abu El-Haj diagnosed its economic and political effects on the Palestinian people. Therefore, the task is to interrogate what this means for IL and legal academia at large.

The Juridical Evasion Complex

When legal language refuses to acknowledge this structure, it becomes complicit. That complicity permeates legal pedagogy, international institutions, and treaty architectures that simply manage its aftermath. Tout underscores this silence as a function of IL’s geopolitical architecture, shaped by settler states, like Israel, the U.S., Canada, Australia, whose foundational myths the law protects. Tzouvala and Saito identify this architecture as structured civilizational hierarchies masquerading as universality.

In Palestine, this manifests as legal fragmentation that reduces the Nakba to a historical episode (pp. 6ff.), frames Gaza’s siege as humanitarian tragedy rather than colonial violence and treats apartheid as debatable. Similarly, Zionism’s ideology, theorized by Sayegh in 1965, eventually led to the adoption of Resolution 3379 in 1975, declaring Zionism a “form of racism and racial discrimination”, only to be retracted under US efforts in 1991 after convincing the Palestine Liberation Organization. Even landmark legal moments such as the ICJ’s 2004 Advisory Opinion on the Separation Barrier and 2024 litigation acknowledge occupation but resist confronting the settler colonial project as a feature of the Nakba that sustains it. Likewise, UNSC Resolutions 242 and 1544 advising Israel to respect the Fourth Geneva Convention and the vetoed 2011 resolution on settlements illustrate the law’s impotence to confront structural dispossession. Domestically, Israeli law normalizes settler violence under security pretexts (pp. 23ff.).

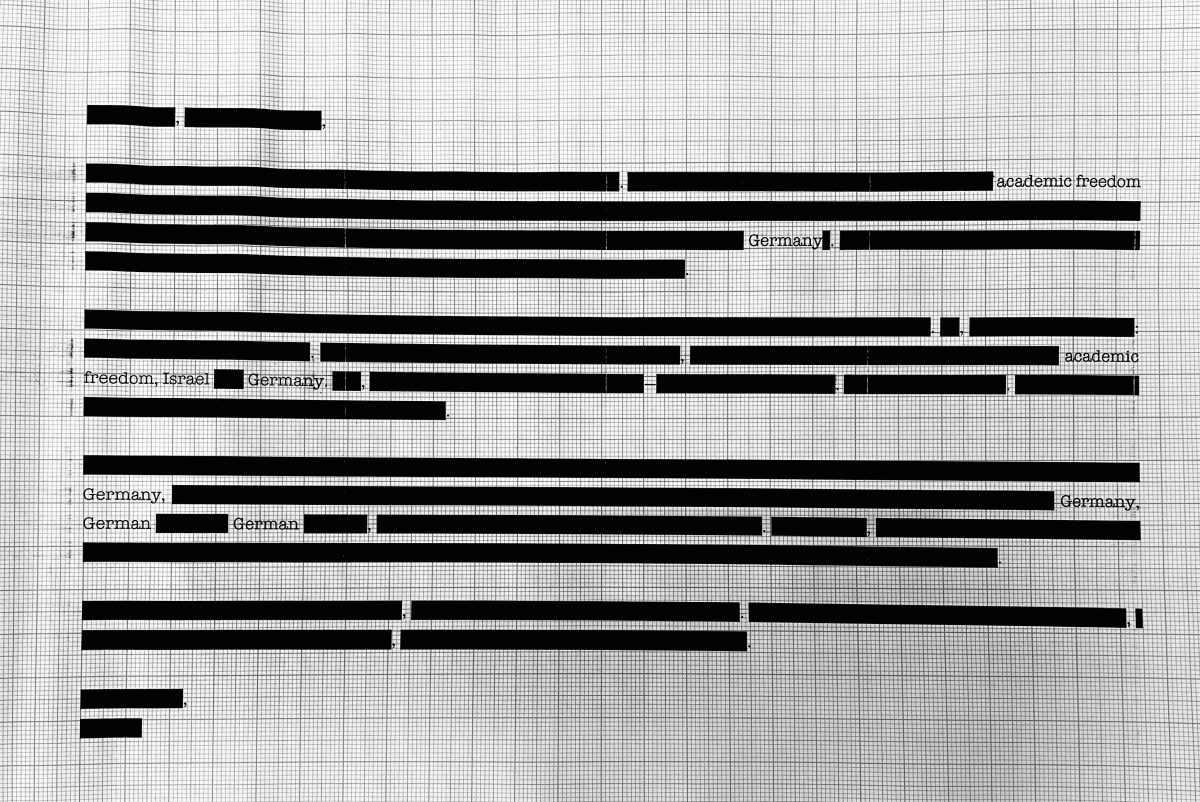

Cases like South Africa v. Israel, Nicaragua v. Germany, while significant, are instructive for what law strategically omits. By focusing on procedural metrics (due diligence, arms exports, proportionality) Schwöbel-Patel affirms how Germany and others are permitted to evade deeper questions of complicity in occupation and genocide. Legal formalism’s fixation on intent, proportionality, and state identity, leaves the infrastructures of the Nakba unexamined. The core omission therefore is not Israel’s genocidal intent but the law’s incapacity to grasp a century-long project of replacement. In this frame, the legal recognition we observe is triggered by Palestinian death, not by the structures that produce it. Crucially, these cases are not bilateral disputes between occupier and occupied, they implicate third states whose passive or enabling legal postures help sustain the colonial relation. As affirmed by the UN General Assembly (pp. 2 and 8), states are obligated not to assist unlawful situations, yet they continue to do so.

It becomes visible that the non-universal “rules-based international order” and IL’s reliance on a presumed universal framework lay bare the contradictions of attempting to regulate a deeply unequal world. In an era where Western states routinely sideline international norms, what is achieved by invoking a legal order indifferent to its own principles? IL functions as an enabler, as courts like the ICJ and ICC may grant Palestine visibility, but visibility without political rupture is not power nor emancipation.

The Pedagogy of Silence

Within academia and practice, framing Gaza’s destruction through terms of legality creates a false dichotomy between law and domination (p. 78), obscuring how IL sustains the very structures it claims to regulate. As Chandler notes, in an environment of majoritarian silence, even having an opinion becomes resistance. In Palestine, law displaced political struggle, recasting resistance as legal petitioning. Victims are petitioners, narrating their suffering within a framework that evades its own complicity. International legal academia therefore performs a rhetorical balance that flattens the profound asymmetries maintained by settler states. It remains unsurprising that most legal curricula omit racial capitalism, settler colonialism, and legal violence, training lawyers to manage crises not to interrogate their production. Yet, Gaza has begun to puncture this consensus, revealing IL’s complicity in state violence and responses suggest a growing disillusionment.

Nonetheless, overreliance on legality alone risks reinforcing colonial structures by legitimizing the very regimes that sustain them. Still, this doesn’t demand abandoning the law but politicizing its use. Working within its limitations means asking not merely “is this legal?” but “is this fair?”. If international legal legitimacy rests on an appeal to justice, then Palestine demands new legal thinking.

Just as “crimes against humanity” emerged after World War II, there is a growing call within the profession for a parallel framework to address the constant structural violence in Palestine.

The Language of Indigeneity?

Even so, the employment of settler colonialism as a legal category invites critique as the reach of mere utilization of legal language within political struggle remains rightfully contested (pp. 1f.). Settler colonialism might risk oversimplification when “Indigeneity” is detached from political context. It must be understood as a political category. Fanon and Césaire’s juridical notion of the “native” therefore foregrounds colonization’s political core (pp. 152ff.).

In Palestine, Barakat observes (pp. 351f.) the issue to be continued presence instead of Indigenous disappearance. Methods of elimination may differ, but the objective aligns with Wolfe’s concept of structural genocide. Israeli court rulings denying Bedouin land claims illustrate liberal recognition’s limits: historical continuity and present habitation are both erased. While Canada and Australia have formally acknowledged Indigenous rights, exceptionalizing Israel occludes how “recognition” itself stabilizes settler sovereignty. Barakat urges (pp. 359f.) to use Indigenous Studies to explain Zionism and theorize Palestinian experience. Yet, reliance on Indigenous rights paradigms alone for land claims with definitions of Indigenous people in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and doctrines like Aboriginal title (e.g Mabo v Queensland (No. 2) risk fragmenting Palestinian political identity by tying recognition to depoliticized criteria of cultural persistence, rather than collective sovereignty.

Nakba’s Legal Concept

Eghbariah therefore rightfully contends that Palestine is best understood not through occupation, apartheid, or genocide, though the situation may satisfy each of these definitions, but through the structural grammar of the Nakba. While ethnic cleansing inaugurated the Nakba, the phenomenon cannot be collapsed into it. Nor does settler colonialism capture its full juridical texture (p. 978).

By privileging “occupation” as the primary lens, IL relegates the Palestinian condition to a past crisis instead of an enduring legal reality (p.83f.), which displaces Palestinians as subjects of rights (p. 939). The emergence of the 1993 Palestinian Authority (pp.96ff.) and Hamas’ rise in 2006 further fragmented the terrain, producing a political mosaic irreducible to occupation alone. Apartheid, meanwhile, remains trapped in analogy, tethered to South Africa’s precedent, with disputes over its onset (p. 948) and extent obscuring its lived realities in Palestine (pp. 664ff.). The label “genocide” fares no better. While the ICJ found South Africa’s case against Israel “plausible” (p. 955), the proliferation of adjacent terms, politicide, memoricide (pp. 225ff.), sociocide, signals the inadequacy of existing parameters. If such terminological hedging fails to encapsulate Palestinian reality, Nakba must be understood as its most coherent articulation of the Palestinian condition.

As a legal concept, Nakba articulates Palestine as a colonial condition (pp. 1ff.) and entails five interlocking dimensions: recognition, return, reparation, redistribution, and reconstitution (p. 897). It names a present regime premised on perpetual fragmentation (pp. 188ff.) besides elimination or segregation alone. Displacement remains an enduring, unassimilable state that denies self-determination, and is structured by dispossession, domination, and ethnic cleansing, far from exile or integration, and central to a juridical regime of perpetual misplacement.

Law Beyond Innocence

Political realities cannot be ignored, but within those constraints, the law remains a tool that must be wielded critically with awareness of its limits. To engage Palestine through the lens of settler colonialism and the framework of Nakba is to expose the limits of prevailing legal paradigms and to challenge the profession to become something other than a managerial class for structural violence. To critique IL is therefore not to abandon it. It is to refuse to accept its innocence. Law remains a terrain of struggle that Palestinians themselves have mobilized strategically to expose contradictions and delay devastation. This must be respected but it cannot become the horizon of our political imagination. Palestine is a mirror held up to IL’s structural biases and justiciability must extend to third parties who materially or diplomatically support settler regimes. As the significance of articulation of the Nakba and its symptoms may stem less from potential criminalization, but from its recognition as a distinct modality of collective domination and dispossession, one must not forget that the intensity of violence in Palestine denies us the privilege of discarding any instrument available in the pursuit of justice and liberation.

Sabrina Seikh studied law at the University of Warwick and Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. She is currently a law student at the Freie Universität in Berlin. Her research focuses on critical approaches to International Law and International Criminal Law.