Joining the Conversation

Teaching Research Methods and Academic Legal Writing for International Law

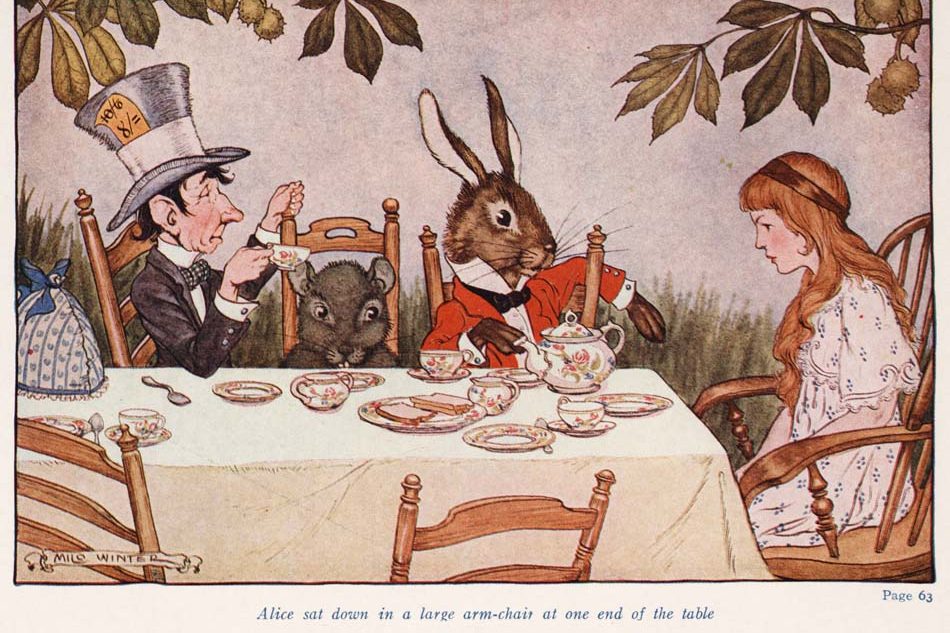

“And what is the use of a book,” thought Alice, “without pictures or conversations?” —

Lewis Carroll, ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.’

In ‘The Outside Keeps Creeping In,’ Sué González Hauck criticises the orthodox methods of legal scholarship. She argues that these methods neglect the ‘non-doctrinal’ and ‘extra-legal’ aspects of the law. I agree with her critique, especially in the context of international law. International law is a global legal system that does not belong to any specific country, culture, or language. It is also a practice of argumentation, not just a fixed collection of rules (Koskenniemi, p. 2). Adopting an orthodox perspective on international law ignores its complexity and diversity, which leads to various problems in legal epistemology, source interpretation, and legal education.

In this text, I will focus on the last issue. I will not restate González Hauck’s critique of the orthodox approach. Instead, I will offer a short ‘pedagogic proposal’ based on my experience as an international law teacher, student, researcher, and writer. I am far from an expert, but I hope to share some insights that might give both students and teachers something to consider. As a student, I struggled with the orthodox teaching methods of legal research in international law. As a teacher, many of my students face similar challenges. My proposal is aimed at undergraduate-level teaching but might also apply to graduate-level academics. Before beginning, I should clarify that these are my personal views and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the institutions with which I am associated.

Teaching Legal Research

As a teacher of methodology and research methods in law, I have rarely encountered students (or educators) who were enthusiastic about these topics. Law students are usually excited about writing on their chosen subject. They often have a specific theme in mind when they start writing their bachelor thesis or research proposal for their LL.M or PhD. Students are passionate about reading and writing on current issues such as free speech and censorship, children’s rights, the risks of artificial intelligence, climate change and environmental problems.

But, sadly, that passion fades away when we talk about actual methodology. This is not surprising. Orthodox methodology courses tend to present an abstract, out-of-context overview of every possible method to their students. This is the same as giving a beginner cook a list of ingredients and leaving them to figure out how to prepare the dish they crave.

Someone in my position might offer an interesting perspective on these courses. I was recently a student myself, sitting in one of these classes, confused by the abstract and distant catalogue of methods. And for the last seven years or so, I have been teaching research methods. Many more experienced scholars have written on the methodology of international law. But I believe CS Lewis is right: “The fellow-pupil can help more than the master because he knows less. The difficulty we want him to explain is one he has recently met. The expert met it so long ago he has forgotten.”

My proposal is to teach legal methods using a tactic that is familiar to Problem-Based Learning (PBL) experts: heutagogy (Hase, pp. 1-10). In this approach, the learners take the lead, rather than the teachers; students are in charge of their own education (Iversen et al., pp. 2-3). The teacher provides some resources, but the learning process is not fixed or linear. Learning is based on the personal needs of the students and aims to empower them to shape their own educational goals.

This proposal changes the way of teaching legal research methods. Instead of giving a list of methods, the teacher (or supervisor) should function as a helper or a resource person. The teacher should listen to the research interests of the students and then suggest what methods will suit them best. The students will begin by informing the teacher of the topics they wish to research and write about. The teacher will guide them in selecting the most suitable method for their interests. Then, the teacher will instruct them on how to use these methods.

The goal is to make methods more concrete and useful for students to reach their writing objectives. To continue with the cooking metaphor, this approach suggests that teachers first inquire about the recipe students wish to prepare. Next, they present a list of relevant ingredients and collaborate with the students to select the best options for their dish. These chosen ingredients (methods) are the ones the teacher should focus on in class.

Writing International Law

My proposal for teachers assumes that students have already chosen their research topic and can also write a research proposal and problem statement based on their interests. But this is not the common situation in class. In my experience, most law students are interested in writing and have a list of ideas. The challenge is to pick an idea that is appropriate to the kind of research they are doing (e.g., essay, paper, thesis) and that accounts for the different stages of their work and expertise (Pahuja, pp. 64-66).

Many students who are about to write their bachelor thesis start with ambitious goals (‘I want to study the evolution of jus ad bellum from Ancient Greece to the UN’) and end up with something less inspiring (‘I’m okay with writing about Article 2.4 of the UN Charter’). This is not the student’s fault, as they usually have no experience in writing longer than a one or two-page essay. Here is where a skilled teacher should help students choose a topic that suits their interests and the time they have for the project.

Choosing a topic — such as the prohibition on the use of force in international law — is important, but it is not enough. How we approach the topic is also crucial and often challenging for many students. As Hildebrand warns, this is where the risks of writing a ‘bad paper’ are higher. For example, some papers or theses may only describe or summarise what scholars A and B or international court C say about Article 2.4 of the UN Charter. This kind of work may be acceptable, but it could be improved if a different approach was taken.

I suggest that the student (and their teacher or supervisor) approach their topic as a conversation. They should see their work as a move in an ongoing dialogue that others are having on that topic. To do this, we should first listen to (and read) what others are saying and then make our own contribution. This approach is especially fruitful when there is some disagreement among speakers. In this case, the writer can choose one of these strategies: (i) agree with speaker A and disagree with speaker B and explain why A is right and B is wrong. (ii) Disagree with A and B and offer a different perspective on the problem. (iii) Agree with A and B and try to find a way to harmonise their views.

Using this approach, the student will first read relevant international law sources and scholarship to see what stakeholders, policymakers, state representatives, lawyers, and scholars are discussing. Instead of addressing the use of force in general, the student will choose a specific debate, such as: (a) whether international law permits States to intervene in other States’ territories to stop human rights violations (Vidmar, pp. 302-306). (b) Whether small-scale armed attacks below a certain threshold are not considered acts of aggression under international law (O’Connell, pp. 153-154). (c) And whether States are forbidden to conduct military exercises or maneuvers on the Exclusive Economic Zone (Prezas, pp. 97-116).

Once the student identifies a disagreement, they write their research proposal using one of the three strategies (i, ii, or iii). This kind of approach helps the student to write clearly and coherently, which can enhance their critical thinking and argumentation skills. It also shows the student’s understanding of the topic and their contribution to the field by relating their work to the existing literature and the current state of knowledge. In addition, it can promote scientific progress by achieving the objective of scientific writing, which is to advance the scientific discourse. This is especially true when students submit their work to law reviews edited by their peers.

By Way of Conclusion

I end this piece with three brief remarks. First, my approach to writing international law pieces is not the only valid one. Other well-known and respected academic writing methods exist and are equally valid. There is no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to writing, and different approaches may work better for different people. Second, I am aware that teachers may not have a great deal of flexibility when it comes to choosing the syllabus for their methods class. In such cases, the proposed approach may be more useful for supervisors or course planners with more control over the curriculum. It is essential for those in charge of designing courses to consider a variety of approaches and choose the one that best fits the needs of their students. Finally, as Garner advises, effective writing requires a lifelong commitment (Garner, p. 52-53) . A big part of this commitment is to overcome our natural fear of criticism and to keep writing. We can never claim to have mastered writing; there is always more to learn.

Henrique Marcos is a lecturer at the Department of Foundations of Law, Maastricht University. In addition, he is researcher at the Centre for Studies on International Courts (NETI, São Paulo University) and Globalization and Law Network (Glaw-Net, Maastricht University).

Henrique, thank you for sharing this masterpiece with us! As a student, I have struggled with ‘which methodology I must follow…’ You provided so many insights and hope in your text… I wish we could see more about your perspective on the future of legal methods.