Welcome to another interview of the Völkerrechtsblog’s symposium ‘The Person behind the Academic’! With us we have Prof. Vasuki Nesiah, and through the following questions, we will try to get a glimpse of her interests, sources of inspiration and habits.

Welcome Prof. Nesiah and thank you very much for accepting our invitation!

May I first ask what it was that brought you to academia and what made you stay?

I came to it through the accident of personal history and the opportunities that opened up. I come from a family of teachers and benefitted from the privilege of teaching being the default career option.

In addition, I came of age during the war in Sri Lanka, and a group of faculty at the University of Jaffna (a group that called itself University Teachers for Human Rights – UTHR – composed of both family and family friends) played a pivotal role in advocating for the community during a really challenging phase of the war in Sri Lanka. They were able to marry a life in academia to a life of political relevance in ways that were creative and courageous – not because their scholarship was itself ‘political’ (the uncle I have been most influenced by is a mathematician), and not necessarily because universities are always democratically inclined (they are often elite spaces alienated from even the communities in which they are embedded), and not because I see myself playing as pivotal a role as UTHR (I am not as visionary or as courageous) … but, nevertheless, their example was, and continues to be, inspiring – a calibration point for how to live one’s life in the academy.

This is part of why I have stayed in academia – but I also stay because I developed a love for participating in the social life of ideas, from the classrooms and reading groups, to the pages of books and journals, to the (difficult to chart and bi-directional) trajectory of these ideas outside the university’s walls. In other words, it was all about the people. The intellectual and political communities I stumbled on in legal academia – TWAIL, feminist, NAIL, CLS etc. – have been, and continue to be, critical to this part of the story.

If you were not an academic, what would you be?

My guilty pleasure is the world of design – I spend a ridiculous amount of time looking through the web pages of sites like architectural digest and apartment therapy – with particular interest in the sub-field of tropical architecture and architects such as Geoffrey Bawa. I have a fantasy life of being an architect if I ever leave academia. This is very much in the mode of someone who might stumble into a Jackson Pollock exhibit and wonder how things would look different if we used more purple here, or if we replaced this swirly line with a more squiggly one… i.e. it is the liberating ambition of the outsider who never has to go beyond the speculative.

What sparked your interest in working on feminist and third world approaches to international law?

Well, my feminist and TWAIL orientations (as well as my socialist/anarchist orientations) were not conscious choices so much as commitments and solidarities that had traction because they were the ones that made sense of the world from my location. That said, all the different coordinates through which my ‘location’ might be plotted also pull in different directions, so the intellectual and political implications of this location also feels unsettled, a constant provocation to rethink.

In this process of locating, and relocating, I was fortunate to have stumbled into a law school experience that included teachers and mentors who were both challenging and supportive. Equally, I was fortunate to have been at law school with the other students who I was able to think with as we travelled on a path together. At every stage there were conversations and prolonged engagements that were critical, but their afterlives are not always visible. TWAIL is perhaps the most visible mark of these collective explorations on one of these paths.

Have you encountered difficulties in accessing positivist academic circles?

Yes and no. By teaching international law in a liberal arts program rather than a law school, I have enjoyed a generative and rewarding space for interdisciplinary research. If I tried to access positivist law circles, I suspect that I would find that my publication and teaching record may be illegible to those departments.

If you could, which unspoken rule of academia would you instantly erase?

The hierarchies that continue to be so deeply Eurocentric on all fronts – from which intellectual traditions are privileged, to what kinds of critical analyses are legible within the vernacular of ‘western’ academic discourse, and to the institutions and publication venues that are recognized in the global North’s academic public sphere. There is so much exciting work from scholars situated in the global south who do not make it into our conferences, citation lists, syllabi etc.

Could you share with us three books/persons that have had a major impact on your perception of justice?

I am not sure I have arrived at any conclusions about my own theorization of justice and the impacts it bears out – the ‘owl of Minerva flies at dusk’ and all that – and hopefully I am not there yet. Perhaps what I can share are people whose work I am thinking with at the moment in different projects: Cheryl Harris and Anthony Anghie in a project that speaks to a dialectic between critical race theory and TWAIL, the feminist scholars Dilar Dirik and Veronica Gago as I finalize my international conflict feminism project, and the filmmaker Abderrahmane Sissako and the playwright Jackie Sibblies Drury as part of my current project on international law’s imbrication with the history of slavery and colonialism. Sorry, I think I indulged in some arithmetical gymnastics that made 3 into 6.

Do you believe that religion has had an impact on your perception of justice?

I haven’t reflected on it at length, but it probably had an indirect role because I grew up in a multi-religious milieu – a family that was mostly Anglican, a community that was mostly Hindu, a country that was mostly Buddhist, and friends who were all of the above as well as Muslim, Catholic, agnostic/atheist etc. I pronounced myself agnostic/atheist sometime in my teens. However, perhaps because of the milieu I grew up in, religion has always been mostly about people and social relations rather than more abstract theology, both when it has been mobilized for oppressive purposes and towards more emancipatory ends. Both dimensions have been alive in Sri Lanka with different religious traditions offering alternative vocabularies for justice and injustice that has resonance and traction in different communities. In that sense it was a milieu of intellectual and normative pluralism that required an openness characterized by both risk and reward.

What is your favourite place to read and write? What is always near you when you read and write?

In my home it is often the couch in the family room – my dogs are always sprawled on the couch as well, sometimes contributing to the reading and writing, and sometimes disrupting it.

Outside my home, my favourite place is the Rose reading room in the main branch of the New York Public Library (NYPL). It is a room that has a sumptuous old-world gorgeousness to it, but there is also an eclectic beauty in the silent energy of that space where, at all times, you will have an eccentric cross-section of New Yorkers engaged in various projects under the hush of the library’s ethos. That space – and the subway I use to commute to the NYPL from my Brooklyn home – are the public spaces that make me feel connected to the city in ways that extend beyond my own friends and family. The subway is noisy, smelly and unpredictable in ways that contrast with the Rose reading room but it too makes me feel warm and fuzzy about that extended community, stimulated and energized by these real/imagined connections – and weirdly perhaps, the subway is also a place where I can very easily get immersed in a book if I manage to wrangle a seat.

Which of your publications is your favourite one?

Favourite is not the correct word but Freedom at Sea which I published in the London Review of International Law is the one I am closest to because I wrote much of it as my mother was dying in the fall of 2017. She passed in December of that year and I completed it after she passed. Writing for me is a way to think – and in some circumstances, as in this piece, it also a conduit for my emotional life. Freedom at Sea was the piece that was most difficult to write but also the one that I feel most connected to because of all the thoughts and feelings that are entangled with it.

I admit I haven’t read this one, but it goes straight to my to-read list. Thank you very much for sharing.

Which was the most recent exhibition that you attended? Would you like to share a photo from that exhibition with us?

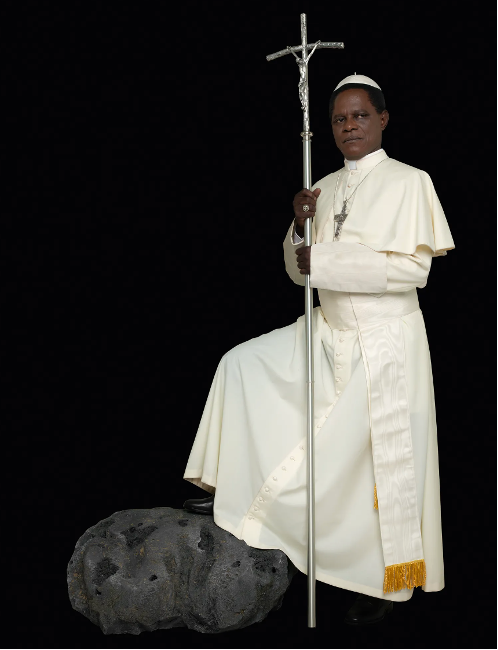

I attended this exhibition call Affirmative Acts – a small but very compelling survey of the Nigerian-Cameroonian photographer Samuel Fosso. Every piece is a self-portrait but also presented as a portrait of others, so Fosso is constantly working with realism in a way that is both a sharp critique and exuberantly playful. Here is one photo that I found especially compelling – perhaps partly because your religion question is still on my mind. This piece is titled ‘the first black pope’, and Fosso has dressed himself in papal regalia with his foot on a meteorite – a portrait of dark virtue, both provocative and humorous.

[Picture taken by Vasuki Nesiah (it is a photo of a photo) and sent to us with regard to this question.]

It does look like a very interesting exhibition!

In which way(s), do you think that international law is misunderstood or wrongly criticized?

We bring multiple projects to international law, and critique sits differently at different political conjunctures – including in ways that may seem to point in opposite directions. In some cases, the critical task is to decry international law’s hypocrisies and contradictions as if the force of international law was principled and consistent. In contrast, in other situations, the task is to show precisely how international law is constituted by “gaps, conflicts and ambiguities” and that this could be enabling not just debilitating. It is this paradoxical, double-edged potential in our own engagement with international law that is sometimes misunderstood.

What are you working on currently? What may we anticipate in the near future?

Well, I am in the final stages of editing my manuscript on international conflict feminism and I am now pivoting more fully to a very different project on international law’s imbrication with the history of slavery and colonialism. I argue that to unpack this racial capitalist history of international law, we need a more expansive and heterodox approach to legal interpretation and legal sources. In that sense, this project is also a methodological intervention about reading international law inter-textually, attending to film, literature etc.

As for my collaborative book projects – it is now over five years since the publication of the volume on Bandung and International Law that I coedited with Luis Eslava and Micheal Fakhri. I am now in the middle of another co-edited project on Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL) with Tony Anghie, Karin Michelson and Bhupinder Chimni.

Thank you very much once again for participating in our symposium and for having taken the time to respond to our questions!

Dr. Nesiah is a professor at the Gallatin School, NYU. She is a founding member of Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL).

Spyridoula Katsoni is Research Associate and PhD Candidate at Ruhr University Bochum’s Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict (IFHV).