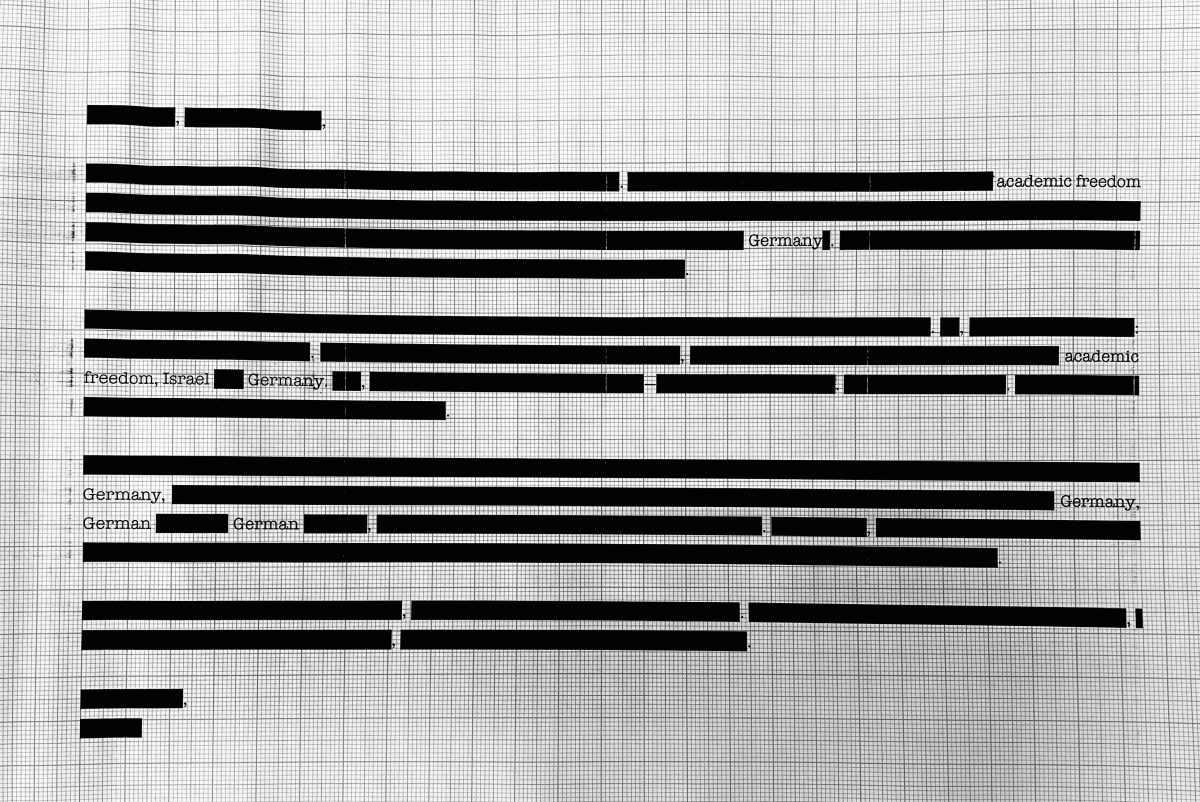

Boycott, Divestment, Sanction as an “Extremist Threat”

German Intelligence Overreaches and Threatens Fundamental Rights

Since late 2023, some countries have imposed unnecessary, disproportionate and discriminatory restrictions on free expression and peaceful protest critical of Israel’s conduct in the conflict in Gaza and the West Bank – including in universities. Such restrictions have been well documented by United Nations Special Procedures mandate holders, including in a report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression. Part of the phenomenon has been the increased securitization of civil society organizations, recently including the United Kingdom’s proscription as terrorist of the direct action group Palestine Action, and the United States’ sanctioning of the Palestinian prisoner support group Addameer.

In Germany, in 2023 and again in 2024 the domestic federal intelligence agency, the Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (“BfV”), classified the “Boycott, Divestment, Sanction” (“BDS”) movement – often supported on university campuses worldwide – as a “suspected extremist threat” against Germany’s free democratic order. In a diplomatic communication to Germany late last year, I and other United Nations independent experts raised concerns that this classification may unjustifiably interfere with the human rights to freedom of opinion and expression, association, and assembly, the right to participate in public affairs, and the right to privacy and reputation. The communication followed concerns expressed in 2019 about a Bundestag resolution imposing certain restrictions on BDS in Germany, which similarly infringed these fundamental rights and risked denying civic space to express legitimate grievances. The Bundestag resolution, along with the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (“IHRA”) definition of antisemitism, influenced the BfV’s recent decision to view BDS as an extremist threat.

BfV’s Classification of BDS as an Extremist Threat

Section 3(1)(4) of the BfV law (“BVerfSchG”) tasks the BfV to gather and process information concerning “organizations […] who violate the principle of international understanding, […] especially the peaceful co-existence of peoples”. The principle of “international understanding” in turn is drawn from article 9 of Germany’s Basic Law and can cover advocacy of aggressive war, grave violations of international law, or support for terrorism (See e.g. 1 BvR 1474/12; Internationale Humanitäre Hilfsorganisation e.V. v. Germany). The BfV classified BDS as a suspected (extremist) case or subject of extended investigation to verify a suspicion (“Verdachtsfall”), which implies that there is, over a longer period of time, reason to believe that there exists unconstitutional behavior (OVG Münster 5 B 163/21, para. 24). Section 16(1) of the BVerfSchG requires “sufficiently strong factual indications” (“hinreichend gewichtige tatsächliche Anhaltspunkte”) for a classification, given the stigmatization and potential interference with constitutional rights that may follow (BVerfGE 1 BvR 1072/01, paras. 68-81ff). The classification means that the BDS movement has become an object of observation (“Beobachtungsobjekt”), which allows, subject to proportionality, for the use of intelligence gathering methods to compile further information, including the use of confidential informants and audio/visual recordings [section 9(2) of the BVerfSchG].

The BfV gave a number of reasons for designating the BDS movement. Firstly, the movement’s founding document, the 2005 “Palestinian Civil Society Call for BDS”, demands boycotting Israel with the aim of “ending its occupation and colonization of all Arab lands and dismantling the Wall”. The BfV interpreted this as a call to end Israel’s existence as a State, thus violating the “idea of international understanding”.

Secondly, the BfV refers to a non-binding, political resolution of the German Bundestag entitled “Resolutely countering the BDS-movement – fight Antisemitism” (“BDS-Bewegung entschlossen entgegentreten – Antisemitismus bekämpfen”) from 2019. The resolution characterized BDS as an “all-encompassing call to boycott, [which] in its radicality, leads to a branding of Israeli citizens of Jewish belief as a whole. This is unacceptable and must be strongly condemned. The line of argumentation and the methods of the BDS movement are antisemitic.” The resolution refers to “Don’t Buy” stickers of the BDS movement, which it asserts “inevitably create association to the N[ational]S[ocialist]-slogan ‘Don’t buy from Jews’”. It does not, however, designate all or certain supporters of the BDS-movement as antisemites (Verwaltungsgericht Berlin 2 K 79/20, para. 88). The resolution concludes that the Bundestag decides (1) not to provide access to public premises administered by the Bundestag, (2) not to financially support organizations that question Israel’s right to exist, (3) not to financially support projects that call for the boycott of Israel or that actively support the BDS-movement, and (4) to call upon all States (Länder), cities and municipalities and all public figures to adopt a similar approach.

The BfV report also observes that among the more than 170 Palestinian organizations that support BDS are Palestinian terrorist groups, namely Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad, and Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.

The Bundestag and the German Government, including the BfV, appear to use as basis for their understanding of antisemitism the controversial working definition of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (“IHRA”), which includes as an example of possible antisemitism the targeting of the State of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity.

Violations and Chilling of Civil and Political Rights

The classification of BDS potentially infringes on human rights. Unnecessary or disproportionate covert intelligence gathering could clearly violate the right to privacy; and the right to reputation could be impacted by public stigmatization of individuals associated with BDS as “extremists” (ICCPR, article 17). The chilling effect of classification on other rights could constitute interferences with them, in particular with the rights to freedom of opinion and expression (ICCPR, article 19), peaceful assembly (ICCPR, article 21) and association (ICCPR, article 22), and the right to participate in public affairs (ICCPR, article 25).

Specifically, the classification risks stigmatizing and chilling legitimate criticism in a democratic society of the conduct of a foreign state, including its serious violations of international humanitarian and human rights law and responsibility for international crimes, and legitimate protest actions aimed at bringing Israel back into compliance with international law. As such, the designation undermines civic-led efforts to protect human rights and enforce international law.

While citing parts of the 2005 “Palestinian Civil Society Call for BDS”, the BfV omits to mention that the title of that document calls for a boycott “against Israel until it complies with international law and universal principles of human rights”, and that a core demand of the document is “recognizing the fundamental rights of the Arab-Palestinian citizens of Israel to full equality”. The BDS movement defines itself as “an inclusive, anti-racist human rights movement that is opposed on principle to all forms of discrimination, including anti-Semitism and/or Islamophobia”.

The BDS call to end Israel’s occupation and dismantle the Wall finds clear support in international law, including the two advisory opinions of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) of 2004 and 2024 (finding the occupation illegal and calling for its end) as well as numerous United Nations resolutions and the findings of human rights mechanisms. Resistance to occupation, exercised in accordance with international law, is also not unlawful, as indicated by the General Assembly and Human Rights Council.

Further, BDS does not call for the violent elimination of Israel’s existence as a State. While some may call for a single, pluralistic State encompassing the peoples of Israel and Palestine, international law protects the freedom of every person to express opinions about the political character of territories, including to peacefully call for the dissolution or creation of States. Accordingly, the BfV’s concern that BDS can be interpreted as questioning the existence of Israel is not a legitimate basis for classifying it as extremist and thus infringing on human rights.

Placing the entire BDS movement under investigation is over-broad and indiscriminate, since it casts unjustified suspicion on the movement as a whole without focusing solely on any specific actors within it that may present a risk to the rights or freedoms of others or other legitimate security or “international understanding” interests. The designation is likely to have a serious stigmatizing impact on a large number of diverse groups and individuals associated with the movement, including human rights defenders, impacting their access to public funding or their ability to organize events or assemblies in public spaces. This is all the more serious given the global public interest in Israel’s response to the Hamas-led attack from Gaza on Israel since 7 October 2023. The designation and associated investigation restrict fundamental rights in a manner that is not necessary or proportionate under international human rights law. The concept of acts against the “idea of international understanding” under German law itself requires a proportionality assessment and does not tolerate blanket restrictions.

BDS as Protected Freedom of Expression

In the case of Baldassi and others v. France, the European Court of Human Rights (“ECtHR”) held that France violated the right to freedom of expression of local BDS activists by convicting them for participating in a call to boycott products from Israel, on charges of inciting economic discrimination against producers of goods in Israel (Baldassi and Others v France). The ECtHR found that boycotts are a protected form of free expression, and that calling for differential treatment is not the same as incitement to discrimination. The applicants were not convicted of making racist or antisemitic statements, inciting hatred, violence, discrimination or intolerance, or committing violence or causing damage. The ECtHR found that the limitation was not necessary in a democratic society, especially in the light of the general public’s interest in the topic and the debate surrounding Israel’s compliance with public international law and human rights. The ECtHR said that there was “little scope […] for restrictions on political expression or on debate on questions of public interest”.

This decision laid the foundations for the French Criminal Court of Lyon (Tribunal judiciaire de Lyon) to similarly hold, on 18 May 2021, that a call for boycott did not constitute incitement to discrimination. A number of decisions by German courts have stated that restrictions on the BDS movement violate the right to freedom of expression, particularly in relation to denial of access to public spaces. Various UN experts have previously expressed concern that restrictions on the boycotts are not justified limitations on freedom of expression (see e.g. here; here, paras. 85 and 88; here; here; here; and here), including for lack of evidence that BDS incites hate crimes, antisemitism or anti-Muslim hatred. They also warned that antisemitism “should not be instrumentalized to silence individuals and groups who oppose the Israeli Government’s policies and practices”. The Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism, developed by renowned Jewish scholars in 2020, recognizes that boycotts “are commonplace, non-violent forms of political protest against states” and of themselves are not antisemitic when directed against Israel.

Influence of the IHRA Definition of Antisemitism on German Intelligence

Germany’s endorsement of the IHRA definition of antisemitism, which is accompanied by illustrative examples, informs the work of the BfV, the Bundestag and other German public authorities. Hundreds of Jewish scholars and civil society actors are among those who have condemned this definition as a weaponization of antisemitism to silence criticism of Israel’s practices, including violations of international law. Although the definition itself is non-binding, its use by the authorities effectively gives it normative force in certain contexts, as in the classification of BDS as an extremist threat.

Many UN experts have criticized some of the IHRA examples of antisemitism as inconsistent with human rights law, particularly the right to freedom of expression. Some examples are considered vague and overbroad; conflate anti-Zionism with antisemitism and thus shields the Israeli State from legitimate criticism; produce false accusations; and are unnecessary because international law already addresses all forms of racial and religious hatred. Further, they are susceptible to being instrumentalized for political goals and to harm Palestinian human rights defenders. And they can have a chilling effect where public bodies use the IHRA’s problematic examples of antisemitism, which due to their vagueness and overbreadth are inherently conducive to subjective application, out of context.

Vague Concept of “Extremism”

The BfV identified the BDS movement as “extremist” in circumstances where “the term ‘extremism’ has no purchase in binding international legal standards” and is “incompatible with the exercise of certain fundamental human rights”, according to the mandate of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism. Worse, the BfV referred to “extremism” without limiting its focus to “violent” extremism (as indicated by United Nations counter-terrorism standards), thus placing under suspicion opinions and beliefs that are not linked to incitement to violence or hatred.

Postscript: The German Government’s Reply

In its reply to the UN communication, Germany admitted that there is no definition of “extremism” in German law and claimed no legal consequences derived from it. It indicated some BDS-related behaviour that has incited violence or hatred against Jews or Israelis, and called to end Israel’s existence and “sedition”, although more information was said to be classified. It queried whether any fundamental rights are affected by the classification, and submitted that any interferences would be proportionate to protect the rights of third parties and to protect democracy. It also noted that the BfV is overseen by supervisory bodies. The IHRA definition was claimed to be a “pragmatic guideline” for recognizing antisemitism which reflects “an emerging state practice”.

Professor Ben Saul is Challis Chair of International Law at the University of Sydney and the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms while Countering Terrorism.