Editorial Decision-Making in Times of Controversy at EJIL:Talk! and the Leiden Journal of International Law

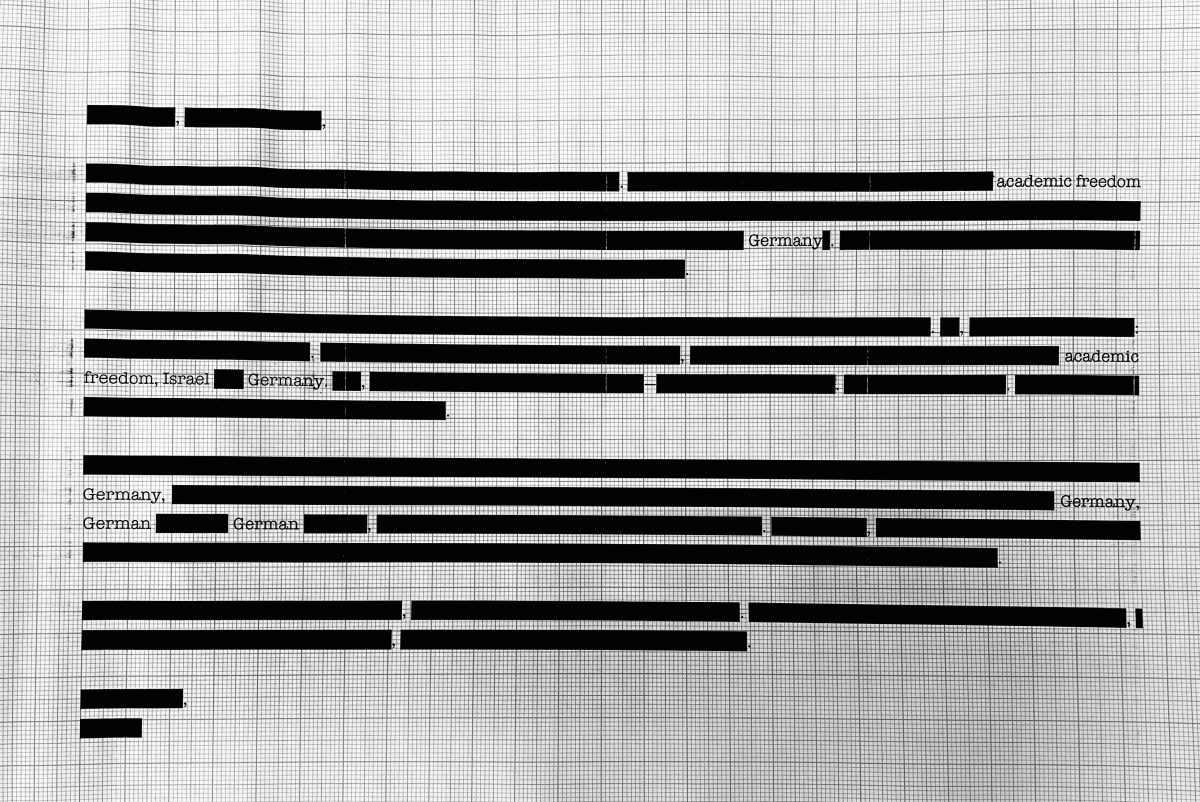

Does an editorial decision to publish legitimise the piece’s author, the author’s affiliated institution or the piece’s content? How should we think about an editorial decision to publish an article that contemplates a possible government act that would violate international law? In this post, I draw from publication guidelines and principles, and the controversies over three 2023 EJIL:Talk! blog posts (here, here and here) and a 2024 Leiden Journal of International Law (LJIL) article, to suggest some ways that we might approach these difficult questions. Other editorial considerations, such as whether international law blogs and journals like EJIL:Talk! and LJIL are amplifying some voices more than others and how much their editors should consider a submission’s military, political and humanitarian context, are just as important but outside the scope of this post.

I argue that publication does not legitimise an author or an author’s affiliation if blind review is conducted properly (‘blind review’ refers to a review process in which editors or peer reviewers cannot see – or are ‘blinded’ to – an author’s name and biographical information). But readers reasonably see legitimisation when there is no blind review or for commissioned and symposium pieces (even if there is blind review). On the other hand, publication generally legitimises content unless editors expressly state otherwise. On the second question I pose above, I suggest that we should support editorial discretion to publish the contemplation of potential government acts that are unlawful. But our approval is less justified if the piece moves from contemplation to promotion, and is unjustified if it crosses the line, for instance, to the incitement to violence or hate speech. Finally, I suggest that we, as readers, should carefully consider how we respond to controversial publication decisions to ensure that we do not inadvertently encourage self-censorship. I welcome feedback and corrections for these still incipient ideas.

Background

In August 2023, EJIL:Talk! published three posts on the identification of custom in international humanitarian law as part of a symposium based on – and this is the controversial part – a panel presentation at an Israeli Defense Forces Military Advocate General conference. The authors of one of the posts were both legal advisors of the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF). About a month later, the EJIL:Talk! Editorial Board and the co-editors-in-chief of the European Journal of International Law (EJIL) published both an open letter they had received expressing ‘dissent and profound disappointment’ for providing ‘a platform for the Israeli military’, and the editors’ reply. The letter suggested that EJIL:Talk! appeared to be legitimizing and amplifying ‘the “scholarship” of regular armed forces of a state actively engaged in war crimes’.

The editors acknowledged that Israel had engaged in serious violations of international law but explained that they assess submissions based on content, not the identity of the authors or their affiliations. Here, they noted, there was nothing controversial about the content. They admitted that they were divided though, on whether publishing papers presented at the IDF conference helped legitimise the IDF.

This question of legitimisation was raised again recently when, on 3 December 2024, LJIL published an article by three authors with Israeli institutional affiliations that described four possible postwar scenarios for administering and developing an offshore natural gas reservoir in Gaza. The fourth scenario imagined ‘partial Israeli annexation of Gaza’. Annexation of territory is a violation of international law. Though the authors acknowledged this, they also noted, for instance, that annexation can be lawful when the international community accepts it and that even illegal annexation can be an important negotiating lever.

Social media went bananas, at least for a law journal article. Readers called for the involved LJIL editors to resign, wondered why the piece was not desk-rejected (‘desk rejection’ refers to early rejection by editors before any peer review), and renamed LJIL the ‘Leiden Journal of Colonialist Appropriation of Resources’ and the ‘Leiden Journal of Legitimating War Crime Profiteering’. The editors quickly published an apology that promised an investigation into ‘reports of significant inaccuracies or omissions’ and emphasized the principle that ‘annexation of territories is unlawful.’

Legitimisation of Authors

Did EJIL:Talk! help legitimise the IDF? The editors were divided on this question. Legitimisation, they said in their 2023 response, lies ‘in the eyes of the beholder’. They are surely correct but I argue here that those of us who see publication as legitimising authors or their institutions are wrong, subject to the caveats below.

Relevant publishing principles and guidelines generally require academic publication decisions to be based solely on a piece’s content, not the identity of authors or their affiliations (e.g., here and here). EJIL and EJIL:Talk! follow this principle (here and here). This means that, at least in theory, publication only legitimises content because content is all that can be and is considered. Publication cannot – and we readers should not believe that it does – legitimise authors or affiliated institutions.

This distinction between author and content does not pop into our minds because when we read a blog post or article, we see author and content side-by-side and then we judge credibility and see legitimisation for both. But the post or article presumably has not been judged like this. Reviewers in double blind peer review and editors in triple blind-review (where editors involved in decision-making do not know author identity) judge the manuscript without author information, and non-blinded editors (EJIL:Talk! does not disclose on its website whether submissions are blind-reviewed) are ethically bound to disregard author identity.

The problem, of course, is that not all editors disregard author identity even if they should. And many journals and blogs do not transparently explain (and thus readers do not know) how author identity is handled (for a rare exception, see this EJIL editorial). Even worse is when the piece is commissioned or is part of a symposium like the one that triggered the controversy. Symposia contributions cluster around a single topic and, at EJIL:Talk!, appear to be directly solicited for review of a book (e.g., here and here), arise out of organization reports (e.g., here and here) or are developed, like the three posts on custom, from conference presentations (e.g., here). Given that in all these instances, the editors presumably have pre-approved in advance the contributors or at least the report or conference, they should not be surprised that readers see legitimisation when, perhaps in theory, there should be none. The authors of the open letter even speculated that members of the EJIL:Talk! board had attended the conference which, if correct, would be additional reason to see legitimisation.

Legitimisation of Content

Did the LJIL piece legitimise the Gaza reservoir article’s content, such as the possible unlawful appropriation of natural resources and annexation, as some critics suggested (here and here)? I think one could reasonably believe that it does, at least to a certain extent, unless the journal explains otherwise. Publication, after all, is an endorsement of the quality and legitimacy of a manuscript’s content, even if not necessarily agreement with its arguments or conclusions. Editors and reviewers of prestigious journals like LJIL spend many hours carefully vetting the rigour, quality, importance and reasonableness of content. LJIL’s editorial statement emphasizing the illegality of annexation indeed seems to be at least in part a response to this legitimisation claim.

Rather than reacting after publication though, journals and blogs should consider proactively using disclaimers or ‘flags’ on articles, or better yet general position statements (flags can imply endorsement of all non-flagged articles), to clarify editorial positions on content. Editors can pre-empt or at least control anticipated criticism of controversial pieces by soliciting counter-viewpoint articles or comments. They should select reviewers with special care to ensure a balanced review and, to better predict blowback, ask reviewers to rate the level of controversial material. Encouraging authors to address their work’s social implications, including the reasonable (and not so reasonable) inferences that should be drawn, can proactively address reader concerns and probably would have been helpful in the LJIL article.

Publishing on Hypothetical Future Violations of International Law

How should we think about an editorial decision to publish an academic article that contemplates a possible future governmental violation of international law? Editors of law journals, as in other fields, retain broad discretion to select manuscripts for publication. Cambridge University Press (CUP), LJIL’s publisher, encourages ‘viewpoints which are contested or controversial’ but refuses to publish ‘work that directly or intentionally incites violence, racism or other forms of discrimination and hatred’. CUP also follows the University of Cambridge’s position on freedom of speech, which allows for controversial or unpopular opinions ‘within the law’.

My research did not turn up any clear guidance on this issue but I hope that few readers would insist on depriving editors from having the discretion to publish a piece that contemplates an unlawful government act as part of a balanced, well-researched, rigorous, methodologically transparent academic inquiry (I am not suggesting that the LJIL article met these criteria and any inaccuracies or omissions that the LJIL editors find in their investigation should be corrected). After all, sadly, governments break the law all the time. The authors should make the illegality of the acts clear and unequivocal, and cannot cross the line into prohibited hate speech or incitement to violence.

Because editors have the discretion to approve something does not mean though that they should – the EJIL:Talk! and EJIL editors agreed that they ‘should not publish pieces that are aimed at promoting international crimes, or other serious violations of international law’. Did the LJIL article promote (or merely contemplate) the unlawful partial annexation of Gaza? This, to me, is debatable. But given Donald Trump’s plan to own and develop the Gaza Strip, the authors of the LJIL article unfortunately may have been more prescient than perhaps even their critics imagined.

Criticising Editorial Decisions

Editors face difficult dilemmas and choices when they receive a manuscript with controversial content or from a potentially controversial author. I hope to persuade you that we readers also have important choices to make when responding. As a recent Mellon/Scholars at Risk Academic Freedom Fellow, my research team and I are building on existing scholarship to understand how intense public criticism – especially when magnified by the viral power of social media – can cause legal scholars to avoid researching certain topics, even when they are not the ones who are directly criticised. There is no reason that this type of self-censorship does not equally apply to editors. We readers should, without fear or inhibition, criticise academic publishing decisions but, I suggest, we should at the same time consider how that criticism can be best expressed to encourage thoughtful debate. The EJIL:Talk!, EJIL and LJIL editors are surely self-confident enough to not let criticism affect their future editorial judgment but not every editor will be so principled and firm. I, for one, want to continue reading the work that they or we might find provocative, controversial or even potentially offensive.

Author’s note: After this post went through peer review and was finalized, LJIL published a ‘Special Issue Addressing Issues and Concerns Raised by the Publication of the “Gaza Marine Article”’. The Special Issue includes an Editorial addressing issues and concerns raised by the publication of the article, a Perspective in which the authors address the concerns and reflect on the timing and context of their article, a Corrigendum by the authors correcting some of their errors, and a commissioned Critique by three experts on Palestine and international law. An Internal Review Document prepared by members of the LJIL editorial board that identifies omissions and inaccuracies in the article is appended to the Editorial. In their Perspective, the authors clarify that they did not intend for their article to endorse the possibility of annexation. Although the Special Issue did not impact the content of this blog post, it provides important information about the academic rigour of the article, weaknesses in LJIL’s editorial processes, and additional considerations for discussing possible governmental acts that violate international law.

This blog post was prepared in part with support from the Mellon/Scholars at Risk Academic Freedom Fellowship. Thank you to Dr Amy Kapit, Senior Program Officer for Advocacy, Scholars at Risk, for her valuable feedback.

Stewart Manley is Assistant Professor at the School of Law and Criminology, National University of Ireland, Maynooth.