Protesting and Teaching about Israel-Palestine in The Netherlands, and the Problem of Double Standards

While Dutch academic institutions swiftly and unambiguously condemned Russia’s aggression of Ukraine in February of 2022, soon thereafter accompanied by sweeping institutional sanctions, they have mostly refrained from responding in the same manner to atrocities, including scholasticide, in Gaza. To make matters worse, campus-based protests directed against Israeli violence have frequently been met with political condemnation and disproportionate police violence. This volatile situation has put a great deal of pressure on the enjoyment academic freedom in the Netherlands. The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) has defined academic freedom as ‘the principle that staff members at academic institutions are free to conduct their scientific research, disseminate their findings and teach’. The KNAW goes on to explain that ‘this freedom extends to’: (1) the choice of topics to be investigated; (2) the choice and application of own research questions and methods; (3) access to sources of information; (4) the publication and sharing of information through conferences, lectures and membership of academic groups; and (5) the choice to enter collaboration with academic partners, and the realisation of academic higher education.

Unfortunately, as we discuss in this blogpost, the practices at many universities in the Netherlands reflected an intolerant approach to academic freedom, particularly when it came to how one taught and researched (aspect 1) on the topic of Israel’s treatment of Palestinians and who to collaborate with (aspect 5) when serious questions arose about universities’ partnerships with Israeli universities which are criticised as complicit in Israel’s atrocity crimes. In light of this volatile situation on campus and double-standards, we ask the question: what room is there for students and academics to exercise their agency in relation to academic freedom in relation to critical perspectives on Palestine, and to what extent have universities served to support or curtail this?

Dutch Academia’s Response to the Russian Invasion of Ukraine

On 4 March 2022, just eight days after Russia invaded Ukraine, all Dutch higher education institutions issued a joint statement expressing that they were ‘deeply shocked by the Russian military attack on Ukraine’. They condemned Russian aggression as ‘a direct attack on freedom and democracy, the fundamental values on which academic freedom and cooperation are based’. The universities announced an immediate freeze of all formal collaborations with Russian educational and research institutions. This included halting research and teaching partnerships, cancelling joint academic events, and excluding Russian institutional participants. Individual universities immediately echoed this stance in their own statements, responding promptly to a call from the Netherlands Minister of Education, Culture and Science, Robbert Dijkgraaf, issued on the same day.

Dutch Academia’s Response to the Gaza Conflict

In contrast, Dutch universities have yet to collectively condemn the escalating violence in Gaza. Despite calls from staff and students, including a collective petition signed by more than 3,000 in October 2023, urging a stance similar to that taken on the Russian aggression directed at Ukraine, Dutch academic institutions have remained largely silent. Some, like Utrecht University, sought to explain and justify their position. On 24 October 2023, its Executive Board stated: ‘We understand the call to take a stand. However, that is not our role […]. We are a university, not a political institute.’ The President of Leiden University’s Executive Board offered another explanation. In her view, the academic community had been unified in support for Ukraine but was deeply divided over Gaza. On 21 November 2023, she said: ‘Some believe that Israel is fighting for survival whereas others speak of genocide of the Palestinian people. Those are two strong, almost irreconcilable positions. Speaking out on this issue would only cause more polarisation.’ Similarly, the rector magnificus of Erasmus University Rotterdam noted on 6 February 2024: ‘When it came to the situation with Ukraine, the reaction was less polarised. It divided the community less […]. Furthermore, there was a clear call from the Dutch government to start a boycott. It explicitly asked all Dutch universities to cut ties with Russia and Russian universities and to raise the Ukrainian flag in solidarity.’ Only a few weeks ago, at a recent meeting on 2 July 2025, Rector Hester Bijl of Leiden University essentially made that same point to explain why her university was still reluctant to act decisively.

Thus, while every university campus in Gaza, its classrooms and its libraries lie in ruins, Dutch universities have until recently chosen silence in relation to flagrant denials of academic freedom of Palestinian scholars and students, while simultaneously restricting the space available to critically discuss this topic on most Dutch university campuses. When asked why Israel-Palestine warranted a different response from Russia-Ukraine, the Boards of Dutch universities pointed to government policy and a broader societal consensus that Russia was in the wrong. The reason for silence, then, appears not to be based on the principle of academic freedom at all, in the sense of how it was described by KNAW and others, but rather its opposite: deference to the political mood of the government.

Escalating Protest and Political Backlash

As the Dutch universities’ self-imposed silence and doing-business-as-usual continued in the name of ‘academic freedom’, frustration grew across Dutch university campuses, and student protests intensified, supported by many staff members. These demonstrations were met with verbal hostility from Dutch politicians and with physical hostility from some universities’ campus security and the Dutch police.

We have seen incidents of disproportionate police violence inter alia in Amsterdam, Nijmegen, and Leiden. The behaviour of the police in response to a recent protest at the Wijnhaven building – part of Leiden University – on 6 May 2025 had a deep impact on the Leiden academic community. Also in May 2025, at Radboud University Nijmegen, there was considerable, campus-based violence.

University policies on protest and security tightened. At Leiden University, for example, uniformed and plainclothes guards were temporarily introduced in 2024 to monitor campuses. At Utrecht, new restrictions curbed lectures and sit-ins related to Gaza and instructed lecturers how to teach and engage in dialogue on this topic. This trend of increasing securitization and lack of confidence in staff’s ability to teach or organize events on the topic, and students’ right to protest, continues to this day. On 14 May 2025, the Dutch universities jointly produced a directive for protests at research universities and universities of applied sciences. Leiden University quickly followed with its own revised house rules, which were even stricter than before. According to these new rules, ‘it goes without saying that our teaching, research and operations should not be disrupted’ by protests at Leiden University, ‘wearing face coverings is not permitted [and] anyone wearing one will be asked to remove it’, and ‘setting up encampments or staying overnight in university buildings’ is forbidden.

There has been a correlation between inflammatory statements made by politicians in the Dutch Parliament and the degree of violence used by the police against the pro-Palestine protesters. During a 14 May 2024 parliamentary debate on a pro-Palestine protest at the University of Amsterdam that began 6 May 2024, Reinder Blaauw of the right-wing Party for Freedom (PVV) praised ‘the decisive action taken by the riot police against the anti-Semitic mob that terrorized the University of Amsterdam for days’. Blaauw failed to distinguish between isolated violent acts and the majority of peaceful demonstrators. Claire Martens-America of the moderate-right Peoples’ Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) made reference during the same debate of ‘English-speaking, masked rioters’ and ‘anti-Semitic posters’, again without providing any evidence to support her accusations. Though some voices in Parliament expressed sympathy for the student protesters, they were in the minority.

Following continued protests, on 8 June 2024 the leadership of all Dutch universities issued a joint, collective statement in a national newspaper. While lamenting that ‘a few [pro-Palestinian] protests […] have degenerated into occupations, provocations, violence and vandalism’, they also acknowledged that ‘the question behind all these protests is a legitimate one: how do we engage with our sister institutions in areas of major conflict?’. But then they undermined their supposed neutrality by defending ongoing ties with Israeli and Palestinian institutions, again claiming that their position depended on the prevailing political mood of the Dutch government: ‘If the values enshrined within the academic ethos […] do not stand in the way of collaboration with Israeli and Palestinian universities, then we see no reason to reconsider or cut these ties. […] We will only consider cutting ties with an entire country if the Dutch government strongly urges or advises us to do so, as was the case with Russia’.

In response, over 1,100 university staff members signed an open letter supporting the students’ protests, denouncing university complicity ‘with the ongoing genocide in Gaza, as well as decades of occupation, apartheid, and ethnic cleansing carried out by Israel on the Palestinian people’.

Throughout 2024, inflammatory responses by Dutch politicians against the pro-Palestine protests continued, in very strong terms. For example, on 6 October 2024, VVD leader Dilan Yesilgöz supported an ambiguous accusation that Dutch Railways facilitated anti-Semitism by allowing demonstrations at train stations. One day later, Geert Wilders, the country’s most influential politician, tweeted a photo of Middle Eastern-looking pro-Palestine protestors, captioned: ‘Get that scum out of the country’.

Yesilgöz continues to suggest that Pro-Palestina protesters are extremists that approve of terrorism, and that some within the biggest social-democrat party are supporting them. In the run-up to the elections at the end of October, she speaks constantly about extreme left-wing radical forces within the social-democrat party, PvdA-GroenLinks. When asked who these people are exactly in a talk show on 15 June 2025, she replied that ‘those are the people who say that October 7 in Israel was an act of resistance. Who justify the campus occupations along with all the destruction and misery involved. Who try to downplay the violence against the police’.

Facing increasing pressure from within, some universities established advisory committees. Most of these committees, including at Leiden University, have yet to produce firm conclusions – pending that advice, exchange programs with two Israeli universities were put on hold in May 2024. Others, including Radboud University, Tilburg University and Utrecht University, have suggested cutting ties with some partner universities in Israel. The University of Amsterdam announced its intention to cut ties to Israeli universities, but soon thereafter backtracked on this decision. Wageningen University is not breaking ties with Israeli universities, and thus more than 400 of the 7,044 employees of Wageningen University have decided for themselves to no longer collaborate with Israeli universities. Perhaps the most far-reaching, and comprehensive advice has come from Erasmus University’s Advisory Committee Sensitive Collaborations (ACSC), which on 26 May 2025 produced a 41-page report that outlined various examples of institutional entanglements in rights’ violations and advised immediate or conditional suspensions to Bar Ilan, Haifa and Hebrew Universities in Israel.

Threats to Academic Freedom

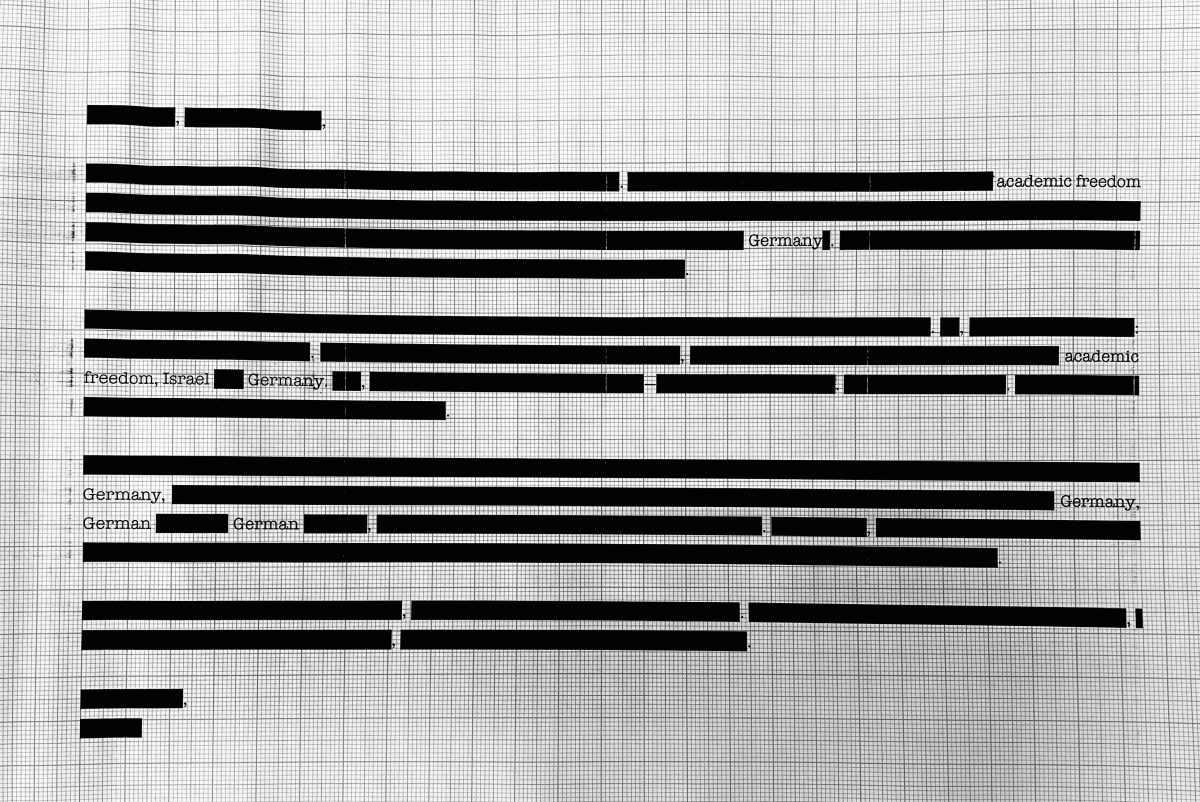

All this takes place in a political climate in which academic freedom is threatened by various measures. Reflecting on their earlier definition of academic freedom, as we outlined earlier on in this blogpost, a recent report of the KNAW of 15 May 2025 notes how systematic screening by university administrators of staff and students who come into contact with so-called ‘sensitive knowledge’ might improve knowledge security, but unduly infringes on academic freedom in that it potentially restricts with whom one may work and collaborate. As we have elaborated in this article, myriad threats to both students and staff have created a very volatile situation, not only in relation to with whom one may collaborate, but – especially in the case of Utrecht – patronisingly telling staff how to teach on the topic. The report also notes that, ‘due to polarization and coarsening, Dutch scientists who participate in the societal debate are increasingly confronted with intimidation, hatred and threats.’ It further notes that ‘women and young researchers in particular experience hatred, threats and intimidation. Strong negative reactions occur particularly around research on polarizing, sensitive or socially relevant themes, such as […] the war between Israel and Hamas’. The KNAW report further argues that fear of intimidation can lead to academic self-censorship. Finally, the KNAW calls on universities not to refuse external speakers solely based on their dissenting political or social views to ensure there is room for debate, and reminds that ‘in their societal role, knowledge institutions should not only provide society with scientific knowledge, but also facilitate dialogue, especially when it comes to controversial issues, such as the war in Gaza’.

On 22 May 2025, a round table discussion on academic freedom took place in the Dutch Parliament. The threats to academic freedom were outlined in various position papers. Issues that recurred in almost all papers included: the increasing pressure on free speech on campus, threats and intimidation of scientists (also online), the difficulty that universities have with ‘controversial’ speakers, the social and political polarization, the increasing grimness of the debate and the perceived self-censorship among students and staff.

On 30 May 2025, the Rectors of the Dutch Universities issued a Statement on Academic Freedom. They notice that, in the Netherlands, ‘there is a growing political tendency not only to question science as a system, but also to actively steer the content of scientific debate and education’. In their purported defence of academic freedom, the rectors promised to ‘launch a broad dialogue on academic freedom […]. A conversation about the tensions currently manifesting on campus, about what the university stands for […]. About balancing the right to protest with ensuring a safe environment for all; between taking freedom and allowing space for others’. However, such promises ring hollow when there is evidently a selective approach about which situations matter, and which do not: a moral consistency is needed.

A Matter of Institutional Legitimacy

Moral consistency in how universities respond to atrocities is not just a matter of principle. It also affects institutional legitimacy. If universities cannot explain or acknowledge their double standards, other than by saying that they are just following government policy, they should not be surprised when students and staff protest.

Meanwhile, Dutch government policy appears to be shifting slightly, which has gained European support. Societal consensus appears also to be shifting in The Netherlands, with 100,000 people participating in the largest Dutch protest in 20 years over the Dutch government’s policy on Israel.

Going forward, we foresee that the way in which Dutch universities navigate these ‘dilemmas’ may also influence how international law is perceived, both in its application and in how it is taught. Silence or inconsistency could undermine the credibility of international legal education and the institutional legitimacy of universities as places of critical thinking and could threaten academic freedom itself.

Yet, institutional legitimacy does not hinge only on decisions taken in university boardrooms. When official voices fall silent, responsibility cascades to the wider academic body. The question then becomes whether we, as administrators, faculty and students, are willing to exercise our individual and collective agency and practise the freedom our institutions wish to protect, or that we merely proclaim the principle of doing so, while practising the opposite. Agency begins the moment we stop treating the university as a remote monolith and recognise academic freedom as a lattice of everyday decisions.

Rethinking the Academy: A Matter of Critical Praxis

When university boards fall silent, responsibility shifts to actors who actually perform the work of the academy. A university is made-up of the students and staff who teach, learn, research and organize.

From our position of relative privilege in the Netherlands, we feel it is important to confront the ethical and intellectual responsibilities of academics during these difficult circumstances, towards a critical praxis. For scholars, a first example of critical praxis is to establish research collaborations with Palestinian scholars and other colleagues whose academic freedom in one way or another is curtailed; a second example of critical praxis is to ensure that Palestinian scholarship is cited in our research and integrated into our curricula. A third example of critical praxis is to establish and nurture platforms where difficult and uncomfortable conversations can take place, such as the longstanding impasse between Israel and the Palestinians. For students, this means organizing, raising the issue in class, arranging Teach-ins, discussing this topic with their professors, and showing up to the events that are organized by staff and students.

Within the spaces and choices taken by university administrators and collective bodies lies considerable room for exercising agency, and therefore responsibility in relation to protecting academic freedom. The everyday acts of students, lecturers, researchers, librarians, journal editors, doctoral committees and academic associations can either strengthen that space of academic freedom or allow it to evaporate. In the end, fighting for academic freedom means refusing silence and standing guard over it, through critical research, praxis, and solidarity.

Otto Spijkers is an assistant professor of international and European law at Leiden University College (LUC), Faculty of Governance and Global Affairs of Leiden University.

Jeff Handmaker is Associate Professor in Legal Sociology at the Hague-based International Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University Rotterdam and a Visiting Research Fellow in the School of Law, University of the Witwatersrand.

Renee Kolpa holds a BSc in International Politics from Leiden University and dual bachelor’s degrees in philosophy and law from Erasmus University Rotterdam. She is now finishing her LLM in International & EU Law at Erasmus University, from which she will graduate later this year.