Spacio-cide from Palestine to Dutch Academia and Back

Colonisation, Separation and Exception

The intensification of Israeli military operations in the Gaza Strip since October 2023 and the ensuing large-scale destruction of Gaza and killings of Palestinians – which are increasingly regarded by international lawyers and other experts as amounting to genocide (see here, here and here in English, French and Italian) – have led to the strengthening and growth of the Palestine solidarity movement across the world. Manifestations of solidarity have also taken place on university campuses, where student-led protests have demanded the severing of institutional ties with Israeli academic partners involved in the systematic violation of the rights of the Palestinian people. However, in many Western universities, both on-campus solidarity with the Palestinian people and academic engagement with Palestine have been met with repression, ranging from outright physical violence to less visible and more mundane practices of control and censorship.

Criticism of these different forms of repression has often been articulated, by both those subjected to them and others, through the legal vocabulary of human rights and by recourse to the concept of academic freedom. In this piece, we propose a spatial reading of these forms of repression by extending sociologist Sari Hanafi’s concept of spacio-cide to academic spaces. According to Hanafi, spacio-cide refers not merely to the seizure, control, and partition of the Palestinian national space during and after the 1948 Nakba, but rather to the systematic abolition of space itself. We illustrate the relevance of this concept in the academic setting by drawing on our first-hand experience in the Netherlands, although we believe it might resonate with other colleagues in Western academia. Our employment of the concept of spacio-cide is intended as an analytical device. It does not seek to unduly transpose a postcolonial framework onto a Western context, nor to trivialise decades of Palestinian suffering and equate them to our own struggles. Rather, we recognise that Palestine often functions as a magnifying glass through which systemic fractures become visible elsewhere.

Academic Freedom and the Limits of Human Rights Discourse

The relevance of human rights frameworks to this discussion is evident. Academic freedom, after all, is “rooted in a number of rights, including freedom of opinion and expression” (para. 38). International human rights law, however, offers limited and piecemeal protection to academic freedom, which is considered to encompass the right of scholars to “freedom of teaching and discussion, freedom in carrying out research and disseminating and publishing the results thereof, freedom to express freely their opinion about the institution or system in which they work, freedom from institutional censorship” (at 27). The enjoyment of academic freedom also requires institutional autonomy (at 17). The cancellation of “scores of courses, lectures, seminars or panel discussions about Palestine”, accompanied by other measures having a chilling effect on academic debates on Palestine, are the most visible manifestations of what the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression has deemed an “assault on academic freedom” (paras. 38-45).

Additionally, peaceful protests, including occupations of university buildings, are protected by the right to freedom of assembly, enshrined among others in Article 21 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and Article 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Although the right to freedom of assembly is not absolute, and can thus be limited and balanced with other competing rights, restrictions need to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis and must meet stringent requirements of legality, proportionality and necessity. From a human rights perspective, the fact that a protest may interfere with teaching activities – and might thus affect the enjoyment of the right to education – does not automatically warrant its prohibition or dispersal. In several countries, peaceful on-campus protests in solidarity with Palestine have been routinely dispersed by riot police. This has happened repeatedly even though “only in exceptional cases may an assembly be dispersed”, for instance “if the assembly as such is no longer peaceful, or if there is clear evidence of an imminent threat of serious violence that cannot be reasonably addressed by more proportionate measures”, or if the assembly causes “serious and sustained disruption” (para. 85). University leaderships have also formulated institutional guidelines on protests of dubious legality, requiring for instance that protesters identify themselves with a university ID card and banning face coverings. However, under human rights law, participating in a protest anonymously is legitimate and can serve to protect the protesters’ privacy and shield them from unlawful surveillance and doxing (para. 60).

We do not deny that this human rights(-centric) framing is doctrinally correct or that it can be tactically useful in advancing legal claims. At the same time, the focus on individual human rights and violations is notoriously insufficient to grasp the structural conditions of which human rights violations are the byproduct. This critique of human rights also underpins scholarship on Palestine, showing how legalistic and de-politicised recourse to human rights law can end up legitimating the subjugation of the weak and reinforcing their oppression.

We suggest that, by adopting a spatial perspective, the closure of academic space on Palestine in Western academia can be better understood as part of the much longer and unfortunate tradition of Palestinian exceptionalism in and beyond academia. In making reference to the concept of spacio-cide, we want to draw attention to how, in addition to capturing the aims and strategies of everyday settler-colonial violence against Palestinians, spacio-cide is also helpful to think about the range of actions aimed at silencing pro-Palestinian advocacy and academic work on Palestine in Western academia. We argue that these exceptional measures do not merely constitute a temporary suspension of academic freedom in the name of security, but rather entail the abolishment of the academic space itself.

Spacio-cide in Palestine

The concept of “spacio-cide” was first coined by the Palestinian sociologist Sari Hanafi in 2006 with a specific focus on Palestine. According to him, “the Israeli colonial project is ‘spacio-cidal’ in that it targets land for the purpose of rendering inevitable the ‘voluntary’ transfer of the Palestinian population primarily by targeting the space upon which the Palestinian people live” (Hanafi, 191). Ten years later, for Hanafi, spacio-cide has morphed into genocide, whose primary aim is not simply the expulsion of Palestinians through the targeting of their land but rather their destruction as a group. Yet, the concept of spacio-cide remains relevant to describe and contextualise the Palestinian condition beyond and before the ongoing Israeli genocidal war on Gaza and to overcome the limitations of international law in addressing it. Because genocide concerns the physical destruction, in whole or in part, of a protected group as such (Article II Genocide Convention), the concept only captures the most exceptional forms of violence directed at Palestinians. Indeed, the limited scope of the concept of genocide has led to the use of several neologisms to depict the totality of crimes against Palestinians more accurately. These have included educide, ecocide, scholasticide, domicide, and medicide, in addition to the suggestion of turning “Nakba” into a legal concept.

Hanafi argues that spacio-cide is realised through three intertwined principles: colonisation, separation and state of exception. The first principle points to the control of the population, the second targets territory directly, while the third mediates between the two (Hanafi, 191, 195).

The principle of colonisation concerns “the everyday practices engineered by various Israeli actors’ governmentalities to ‘manage the lives of the colonised inhabitants while exploiting the captured territory’s resources’” and is pursued through the systematic dispossession of Palestinian space and their economic dependency (Hanafi, 195). The success of these strategies is ensured by the apparatus of military bureaucracy and surveillance, which highlight the “peculiar kind of bio-politics” underpinning spacio-cide, with Palestinians becoming “a purely objective matter to be administered, rather than potential subjects of historical or social action” (Hanafi, 196-197).

The principle of separation rests on two strategies: “the colonial fragmentation of Palestinian space and the administration of Palestinian movement” (Hanafi, 197). Hanafi’s principle of separation describes physical and legal barriers employed by Israel to segregate population and spaces, fragment Palestinian territories into isolated enclaves, restrict movement and connectivity, and ultimately hinder the viability of a cohesive Palestinian society (Hanafi, 198). If the Wall in the West Bank represents the ultimate spatial manifestation of separation, estrangement also manifests in the separated infrastructural systems for settlers and Palestinians and in the Israeli permit regime (also scrutinized by the International Court of Justice in its 2024 Advisory Opinion, paras. 111-156 and 180-229) as well as in the broader territorial fragmentation of the Palestinian national space (the 1948 territories, the Gaza blockade, the West Bank’s partition in three areas, and annexed East Jerusalem).

Finally, a state of exception enables and mediates between the former two principles, allowing for the suspension of normal legal frameworks to facilitate colonisation and separation. Inspired by the work of legal philosopher Giorgio Agamben, Hanafi shows how the Israeli grammar of spacio-cide extensively relies on legal exceptionalism, including the use of emergency laws, military orders, and administrative measures (such as detentions and demolitions) that bypass standard legal procedures, and indeed are largely at odds with international law. Hanafi details how “this state of exception is proclaimed domestically but also at an international level where the norms of international law are tacitly abrogated one after the other” (Hanafi, 199). This also affects the legal status of Palestinians who “are excluded from recourse to the law, but remain subject to it” (Hanafi, 201).

Spacio-cide in Dutch Academia

As explained in the introduction, we do not mean to draw comparisons between the Palestinian lived experience under settler colonialism and our own in a starkly different and privileged context. Nevertheless, we find that the concept of spacio-cide offers a fruitful analytical lens for understanding how Dutch universities embraced Palestinian exceptionalism. We argue that how they responded to various forms of solidarity and academic engagement with Palestine amounts to ‘academic spacio-cide’, ultimately leading to the erosion of academic spaces.

In Dutch academia, the enactment of Hanafi’s principle of colonisation is evident through the repeated recourse to police intervention, effectively infringing on campus autonomy and imposing external control over campus spaces. By having the police violently evict peaceful protesters from campus spaces, Dutch universities echoed the Israeli practice of deploying security rationales to assert spatial control and manage the lives of those inhabiting them. While paying lip-service to the importance of knowledge, critical voices and the freedoms of expression, association, assembly and demonstration, Dutch universities invited repeated instances of police brutality against students and staff protesting the institutional partnerships between Dutch universities and Israeli institutions (see here, here, here, and here for just a handful of examples). Police intervention was justified under the pretext of avoiding disruptions to education, and ironically, protecting the safety of activists. The same logic underpinning the principle of colonisation has informed threat inflation and other academic population management techniques adopted on campus. Measures such as the introduction of mandatory identification checks and the deployment of undercover security guards within university premises underscore a systematic appropriation of campus space. This reinforces institutional control and limits the autonomy and political agency of the members of the academic community, practices characteristic of a colonial logic that transforms autonomous space into a securitised territory. Unsurprisingly, the increase of security measures on campus has neither been aimed at nor resulted in increased safety for academics working on Palestine.

Through deliberate practices of spatial fragmentation and isolation, the actions of Dutch academic leadership also embody Hanafi’s principle of separation. At the institution where we work, restrictive spatial policies, premised on a vague and unsubstantiated assumption of the intrinsic unsafety of discussing Palestine in an academic setting, have required the relocation of lectures on Palestine from centrally located campus spaces to peripheral venues and imposed limitations on the number of participants. This has led to the coerced abandonment of academic spaces. Indeed, by forcing a lecture by Neve Gordon off university premises, the institution physically separated critical discussions on Palestine from the campus environment, paralleling the Israeli practice of spatial fragmentation and displacement. Such measures have had a subsequent self-disciplinary effect, exemplified by organisers proactively relocating an event with UN Special Rapporteur Francesca Albanese to an external venue to pre-empt the possibility of institutional censorship. These measures, resulting in the removal of academic activities from the spaces to which they naturally belong, echo the Israeli separation strategies used in occupied Palestine. There, the arbitrary creation of spatial logics informs different degrees of individual freedom (for example, through checkpoints, the permit regime, and the partition of the West Bank into different areas).

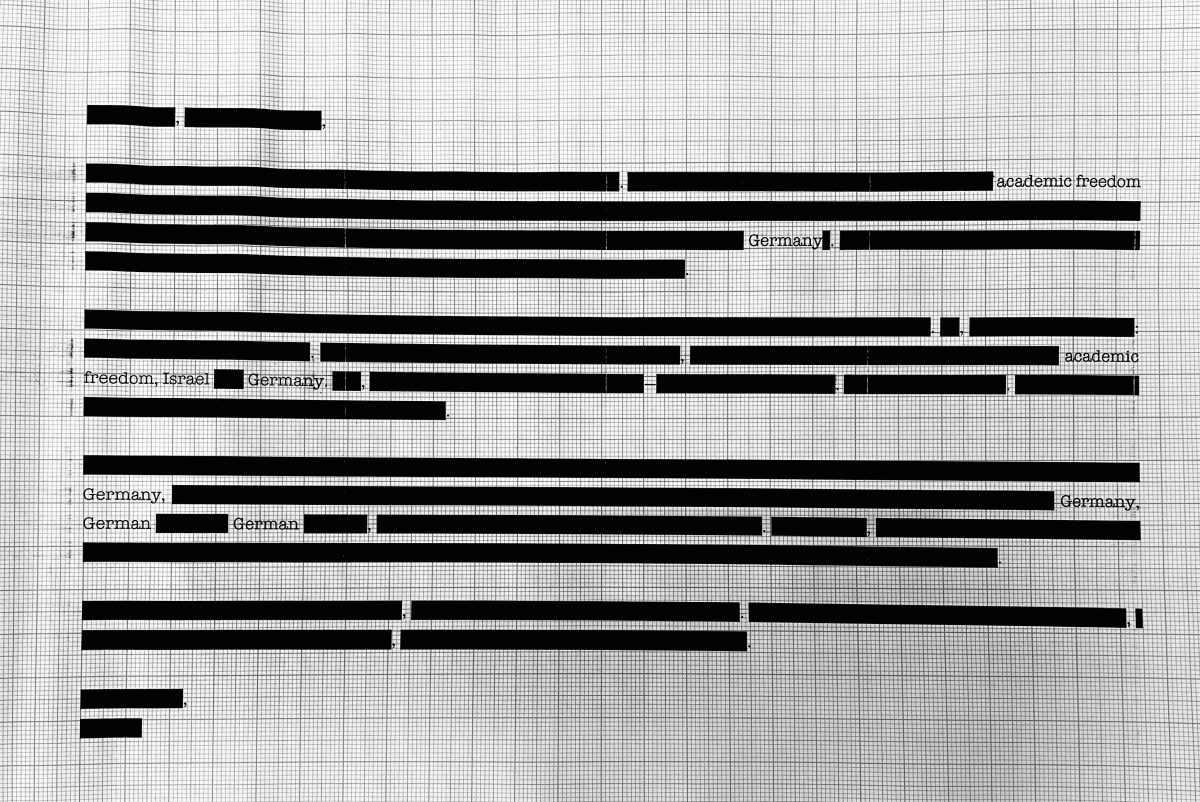

It is not hard to see these policies as the manifestation of a state of exception as conceptualised by Hanafi. Indeed, they have the character of ad hoc emergency regulations and are clear expressions of unambiguous and even explicit application of Palestinian exceptionalism onto the (spatial) life of the university. Notably, past occupations of university buildings by other student groups were tolerated for several days and not evicted by the police, nor have other ‘controversial’ academic activities been subjected to restrictions or prevented from altogether taking place on campus (see e.g. here and here). Dutch universities have further articulated their state of academic exception on Palestine by foregrounding individual emotional responses as justifications for governance interventions or the lack thereof. Palestine is even erased in institutional statements that make generic references to ‘sensitive’ topics, ‘polarisation’ and ‘repression’, even when seizing the concept of academic freedom. By consistently framing academic engagement on Palestine as inherently emotive or sensitive, or even as a threat to academic freedom itself, these discourses shift attention from institutional rationality to the sphere of individual consciousness. In doing so, they frame Palestine not only as an exception to academic freedom but also as an inherently irrational topic – one deemed unworthy of scientific exploration on campus because of its supposed sensitivity. In this way, academic spacio-cide also contributes to the epistemic exclusion of Palestine from universities. In part, this mirrors framings that centre and instrumentalise religious narratives to obscure the complex historical and material conditions that have led to the ongoing dispossession and erasure of Palestinian space, casting them as escaping logic and thus intractable.

Conclusion: Hyper-(in)visibility

In Dutch universities, like in other parts of Western academia, Palestine has become both hyper-visible as a source of institutional anxiety and a rationale for justifying the ensuing closure of academic space, while also being made invisible as a legitimate subject of scholarly engagement on campus and thus worthy of protection under academic freedom frameworks. When universities limit academic engagement on Palestine, they enact a form of academic spacio-cide. This does not merely limit dialogue or establish arbitrary boundaries between permissible and impermissible on-campus activities. Instead, it systematically dismantles the very essence of academia – that is to provide and foster space for intellectual endeavours. Our spatial framing seeks to overcome the limitations of a mere human rights-based approach, which tends to focus on discrete incidents of individual rights violations, without considering their structural dimensions and the exceptionalism reserved to Palestine. By contrast, a spatial perspective highlights the collective nature of the harm done to academic life and its severity. This framing can also invite reflection on how the shrinking and expansion of space may operate differently over time to reconfigure the conditions under which academic life is possible for all. Just as spacio-cide in Palestine involves the erasure of places integral to Palestinian identity and life, academic spacio-cide erases the intellectual and communal spaces where knowledge, and the emancipation that knowledge enables, can flourish autonomously. The consequence is not only a depoliticised university, but a de-academicized one. We should resist these attempts, refuse the normalisation of spacio-cide, and reclaim and rebuild academic and Palestinian spaces.

Alessandra Spadaro works as an Assistant Professor in Public International Law at Utrecht University.

Fabio Cristiano works as an Assistant Professor in Conflict Studies at Utrecht University.