A Circumvention of Refugee Rights?

The Biden Administration's New Rule on Asylum Access at the US Borders and the 1951 Refugee Convention

On the May 11, 2023, the pandemic US border regulation – Title 42 – ran out. To replace it, the Biden Administration put in place a new rule titled “Circumvention of Lawful Pathways” under the framework of Title 8 of the US Code. As it shows striking similarities to unlawful strategies employed by the Trump Administration to restrict asylum (Transit Ban, “Remain in Mexico” policy), the new rule is currently being challenged by advocacy groups in federal courts.

In essence, the rule contains two provisions:

- It establishes a rebuttable presumption of asylum ineligibility for refugees who did not seek asylum or other protection in a country they transited through on their way to the US notwithstanding certain exceptions (“safe transit country rule”).

- Access to the asylum procedure is only granted at a pre-scheduled time and place at ports of entry unless the noncitizen demonstrates that they were unable to access or use the CBP One App (“app appointment rule”).

Dating back to the rule’s proposal in February 2023, serious concerns were raised about violations of the 1951 Convention on Refugee Rights, which is binding to the US through its accession to the 1967 protocol. Under the safe transit country rule, applicants who have not applied for asylum in e.g. Mexico, the most common transit State at the US South border, will automatically be turned away without a material asylum procedure. This blogpost examines whether this rule constitutes a violation of Art. 33 of the Refugee Convention, the principle of non-refoulement (I), by also considering the limited exceptions of the rule (II.), before contrasting the results with the overarching trend towards externalized migration management (III.).

Violation of Art. 33 of the Refugee Convention – Chain-Refoulement and General Threat of Unsafety in “Safe Transit Countries”

Under Art. 33 of the Refugee Convention, contracting states are obliged to not expel or return (“refouler”) refugees in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where their life or freedom would be threatened on Convention grounds. Imperative in this context is that any asylum seeker at the border, even those who have traveled through another country party to the Convention, must be considered a refugee. Refugeehood results from fulfilling the criteria of Article 1(A)(2) of the Convention and does not hinge upon whether another country’s asylum process has been accessed (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Handbook for Procedures, para. 28; Kälin/Caroni/Heim, p. 1370). Based on the countries’ factual control at the border, the imprecise wording (“expel or return”) is interpreted extensively as pertaining to refugees being rejected at the border before entering state territory as well (UNHCR ExCom Conclusion No. 108). The main question is, however, if this can still be considered refoulement, despite the – as the rule insinuates – safe frontier or territory refugees are rejected towards?

The UNHCR has long adopted the interpretation that “(iv) […] asylum should not be refused solely on the ground that it could be sought from another state” (ExCom Conclusion No. 15). Instead, rejection towards a third country is only permissible if refugees“(i) are protected there against refoulement and (ii) they are permitted to remain there and to be treated in accordance with recognized human rights standards until a durable solution is found for them” (ExCom Conclusion No. 58). These criteria formed the basis for UNHCR’s criticism of the European Union’s (EU) Dublin-III mechanism, the most prominent third country rule to date, regarding returns to Greece in 2008. Today, both scholars (Kälin/Caroni/Heim, p. 1386; Graf/Katsoni, pp. 157-159) and jurisprudence (UNHCR [Note on International Protection], para. 20; Inter-American Commission of Human Rights [Canada Report 2000], para. 25; Inter-American Court of Human Rights [Advisory Opinion OC-25/18], para. 122; European Court of Human Rights, [Ilias and Ahmed v Hungary], para. 118) acknowledge that states are required to conduct a comprehensive risk assessment in each individual refugee case to comply with non-refoulement, This assessment should consider both chain-refoulement and the general threat of unsafety in transit countries.

Looking at the risk of (i), chain-refoulement, at the US/Mexico border, there are various reports indicating that refugees do not have access to fair asylum procedures in Mexico, putting many at risk of deportation to their home countries. The second criterion (ii), the general threat of unsafety, is also applicable here. There have been over 13,000 attacks reported against asylum seekers stranded in Mexico under Title 42 over the past two years, in addition to the many attacks suffered under the Trump Administration’s “Remain in Mexico” policy. Black asylum seekers face pervasive anti-Black violence, harassment, and discrimination, including widespread abuse by Mexican authorities and non-state actors.

Similar hazards apply to other relevant “safe transit countries” on the US South border, such as El Salvador, Honduras, or Guatemala. Since the US government has not sufficiently addressed the numerous concerns regarding chain-refoulement and the general threat of unsafety in Mexico and other transit countries, a violation of Article 33 through the third country transit rule must be concluded.

Exceptions – Detachment of Parole, Deficits of the CBP One App and Narrowness of Rebuttals

The new rule does contain limited exceptions. Firstly, it does not apply to those in the US parole program, a voluntary humanitarian entry system by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). But crucially, the parole system is not connected to the asylum process as laid out by the Convention and Title 8 of the US Code. In fact, since the safe transit country rule only applies at the US land border, whereas parole programs require participants to fly to US airports, this exception does not affect the rule at all.

Another exception pertains to individuals who present at a port of entry in accordance with the app appointment rule as laid out above. They can avoid this requirement if they “demonstrate […] by a preponderance of the evidence that it was not possible to access or use the CBP One app due to language barriers, illiteracy, significant technical failure, or other ongoing and serious obstacle.” According to the DHS, this exception only “captures a narrow set of circumstances in which it was truly not possible for the noncitizen to access or use” the CBP One App. Notably, there is no exception for a person’s inability to secure one of the limited CBP One appointments due to insufficient availability, regardless of how long they have waited. Nor is there an exception for someone who lacks the required type of phone, the ability to charge it, access to internet service, or the intellect necessary to navigate the CBP One app. Moreover, the app shows various defects, such as only being available in certain languages (English, Spanish and Haitian Creole) and the facial recognition feature not functioning properly when used by individuals with darker skin. Here, a possible breach of Art. 3 of the Convention, the obligation of non-discrimination in the application of other principles (such as Art. 33) needs to be mentioned. The defects significantly hinder Black refugees, primarily of African descent, to attain an appointment at a port of entry. This constitutes discrimination, at least indirectly, on account of their race and country of origin, making a violation of Article 3 likely.

Lastly, there is rebutting the presumption of asylum ineligibility in the case of medical emergency, extreme and imminent threat to their life or safety or human trafficking. The rule itself clarifies that the rebuttals only apply to a tiny number of people. For instance, the “imminent and extreme threat” exception requires an “imminent threat of rape, kidnapping, torture, or murder”, and does not include “generalized concerns about safety”. Likewise, “medical emergency” and “human trafficking” only apply to a small subset of the endangered refugees. All in all, the exceptions and rebuttals are not sufficient in guaranteeing a procedure in accordance with Art. 33 at the border.

Management or Externalization?

Looking at current trends in migration policy, the US approach is no exception. For the European Union, this development started with the EU-Turkey deal of 2016 and is currently being expanded via the New Pact on Asylum and Migration. The goal is, inter alia, to shift refugee responsibility towards “safe third countries” as well. However, unlike the US rule, even the newly narrowed EU safe transit country mechanism (Art. 36. (1a) lit. b, Art. 45 of the planned Regulation) still incorporates international obligations and the principle of non-refoulement, at least on paper (relevant criticisms can be found here or here).

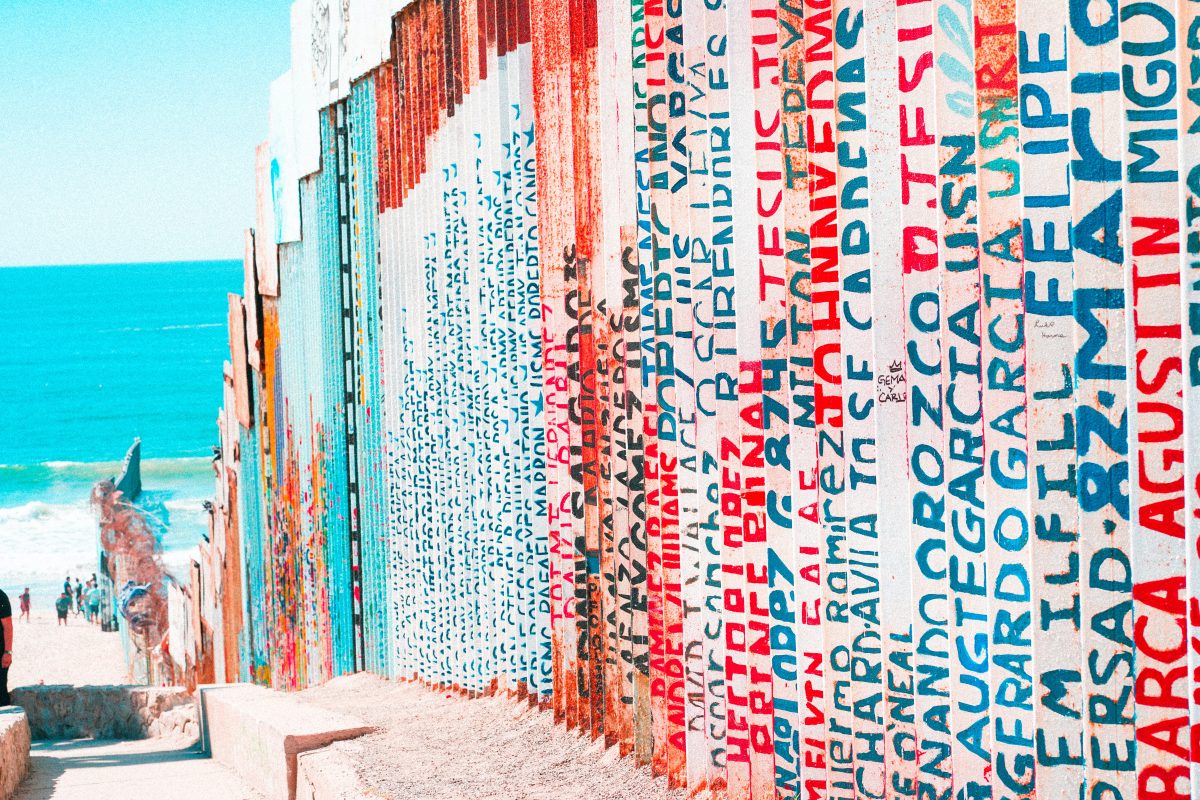

Overall, the attempt to replace regular asylum procedures (and the attached human rights obligations) in favor of sovereign mechanisms, such as parole or bilateral country agreements, can be observed. To ascertain that existing pathways remain underutilized, this approach is combined with methods of hindering refugees from reaching the state territory at all, be it traditionally through border fences or, in the US case, through disproportionate wait times instigated by the app appointment system.

Proponents of these changes argue with the necessity of migration management (here, here or here); supposedly in accordance with human rights obligations. However, as laid out above, the resulting policies oftentimes overstep their boundaries and undermine the existing duties under the Convention, particularly the central guarantee of non-refoulement. The new US rule demonstrates the necessity to oppose this trend of externalization disguised as lawful “management”, as it tends to result in a circumvention of refugee rights.

Author’s Note:

The groundwork for this article was laid during the pro bono exchange with the Refugee Law Clinic Hamburg, the Chair for International Public Law and International Human Rights Law of Prof. Dr. Nora Markard and Columbia Law School, New York. Special thanks go to Carolin Robert, Luisa Nembach and Emma Eder.

Klaas Müller studied law and philosophy and holds a law degree from the University of Münster.