Unlocatable Violence

Reconstructing lost spatial and temporal relationships

Enforced disappearance is not simply the act of violence of its constituent parts: of detention, torture, inhumane treatment, murder. Enforced disappearance operates on a different political register: it not only neutralises the disappeared as political subjects because they are taken away, it also confuses the locus of action and obfuscates the political scene by injecting uncertainty. By doing so, enforced disappearance terrorises a population much larger than the direct victims of violence, creating ambient unlocatable fear (Massumi, pp. 31-48).

In the following lines, I will argue that enforced disappearance’s uniquely dangerous function, on a collective scale, is similar to the function of trauma that contaminates the individual human mind by disassociating the traumatic event from its context. Enforced disappearance, or the act of making one’s location unknown, is an obscure beast. It triggers the imagination of the surrounding community, which in turn multiplies the horrors of violence through the creation of manifold scenarios of possible outcomes. At the same time, the mere unlocatability or indeterminacy of the events of disappearance cancels traditional tools used to advocate and fight for the rights of the victims. It makes political efforts scattered, diffusing their power.

Thus, to fight for accountability, civil society must undertake the arduous work of stitching together evidence in order to narrow down and, as much as possible, locate the violence, in order to reveal its shape. Only then can political action be targeted and find leverage points that can unlock the conflict that has taken form in this erasure. Towards the end of the text, I will introduce a few ways that Forensic Architecture, the interdisciplinary investigative agency, employs spatial and multimedia techniques to undertake that sort of work.

The scattering effect of trauma

Trauma studies literature describes what happens when a person experiences a traumatic event. Through psychoanalytic and medical perspectives, we know that when a body triggers the alarm function that signals threat to one’s survival, the mind of the subject goes to overdrive. All sensors are on full alert. Neurons frantically grab pieces of sensory information, but they do not have time to correctly index them. Instead, they depose them in a messy and confused manner. In this way, the event shatters within the mind and the pieces of perceived data lose track of their origin.

When the person reaches safety and all returns to ‘normal’, the body is in shambles. Shards of traumatic memory are scattered within the brain (and one would argue even other parts of the body). The violence has contaminated the body of the survivor. It has splattered pain through the mind’s archive. The event remains recorded in the body as disassociated fragments that elude understanding: “The traumatic event although real, took place outside of parameters of ‘normal’ reality, such as causality, sequence, place and time. […] outside the range of comprehension, or recounting and of mastery” (Laub, pp. 68-69).

The elusive character of traumatic memory within the individual’s brain resembles the collective trauma of enforced disappearance: a scar that has no locale, that exists everywhere and nowhere, that escapes comprehensibility and cannot be mastered. There is an impossibility of knowing, a lacuna by design. The collective memory of violence consists of fragments of distributed knowledge dispersed across non-homogeneous matter: from the minds of individuals, to recording devices and social media pages. Each of those parcels of memory weigh heavily on the ones carrying it. And within this fog of data perpetrating actors and governments can conceal their responsibility by invoking the impossibility of a coherent narrative. This is further accelerated when governments actively destroy or distort evidence. Eyal Weizman, the director of Forensic Architecture, argues that disappearance often includes both a physical violence (against the bodies of the disappeared) and a narrative violence—against the evidence that such acts ever even occurred, essentially attacking the very possibility of knowing what took place.

Recomposition

In order to fight enforced disappearance and other forms of State violence that rely on narrative destruction, one must undertake a careful process of investigation and reconstruction.

This process that aims towards accountability, also aligns itself with therapeutic aims that require a retelling or ‘reexternalisation’ of the events (Laub, pp. 68-69). The invitation to give testimony, in both contexts, acts as an effort to locate the traumatic events in memory, to communicate them, take ownership of them, and activate them politically.

Yet there is much that eludes verbal language. Multiple theorists such as Jean-Francois Lyotard and Georges Didi-Hubberman (see Lund) have argued that there is something irretrievable in the memory of trauma. Language as a communication tool offers only an abstraction of events that is contingent on the way these events have been imprinted on the soft matter of the brain. Here I consider the brain as media, as another material surface with very distinct physiological properties that allows the inscription of information and conditions their retrieval. The brain codifies experience as neural signals and therefore mediatises it.

In the process of recollection, the brain of the witness recomposes the events anew and tries to restore the original temporal and spatial links that sequence information. Yet we have seen how challenging this can be when trauma is involved: the retelling is always incomplete.

In the cases of enforced disappearance, the prevailing absence of survivors transfers the efforts of recollection of traumatic memories from the psychic register to other forms of material media. Human rights defenders are tasked with reconstructing the events from documents and records that describe only parts of the story. This process requires a patient and careful collection of data and the reconstitution of lost spatial and temporal relationships. It is an act of unfolding information from their host media, peeling off the multiple dimensions of an event from the material surfaces that have captured and compressed it. And then, through analysis, retrieving the lost spatial and temporal links, and stitching the event back together from its piecemeal constituent parts. This results in a recomposition and remediatisation that is however never perfect but always patchy and incomplete, yet more open and transparent about its construction.

Even when there are irretrievable gaps, the task of determining the location and specific form of those voids of knowledge helps sharpen political action and seals them from spreading uncertainty beyond.

Forensic Architecture has experimented with a series of ways to reconstruct such incidents. I will briefly describe three.

The Architectural Media Complex

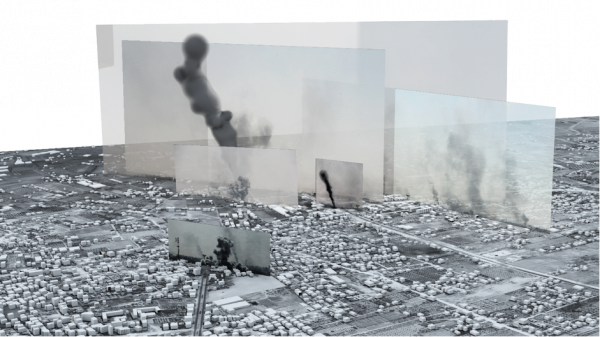

When there are images or videos of violent incidents, whether from professional journalists, passersby, or military perspectives, Forensic Architecture employs three-dimensional models in order to figure out the spatial-temporal relationships of each piece of footage to each other. This technique called the Architectural Image Complex, allows researchers to visualise the undocumented parts of an incident as well as plot trajectories of bodies and objects in a coherent manner. Witness testimony is often also included in these models, cross-referenced and corroborated against the “hard” data. An example for the use of this technique is the investigation into the Bombing of Rafah (Gaza) by the Israeli Defence Force in August 2014, where Forensic Architecture analysed hundreds of images and videos as well as witness testimony and located them within a 3D model to tell the story of one of the heaviest days of bombardment in the 2014 Israel-Gaza war (see image below).

The Image-Complex, Rafah: Black Friday, Forensic Architecture, 2015

Situated testimony

When the only information available comes through witness testimony, Forensic Architecture employs an interviewing technique called Situated Testimony. In this process, witnesses are invited to reconstruct a three-dimensional model of the sites of trauma (with the help of a modeller). By asking witnesses to focus on spatial descriptions, such as the size of tiles, the textures of walls, and so on, the interviewers help them retrieve dislocated memories and externalise mnemonic images of trauma. The reconstructed model then becomes the site for a more accurate testimonial recollection that grounds itself within the spatial specificity of these sites. This technique is used in cases of disappearance and detention in secret prisons or of illegal pushback operations. For example, when former detainees of the Saydnaya Prison in Syria were invited to recreate the prison’s interior from memory, retrieving in this way more details of their torturous experiences there (see image below). Forensic Architecture’s compilation of evidence on pushbacks at the border between Turkey and Greece was used in a recent case before the UN Human Rights Committee, presented by the Global Legal Action Network (GLAN).

Saydnaya Prison Reconstruction, Forensic Architecture, 2016

Data Mining & Pattern Analysis

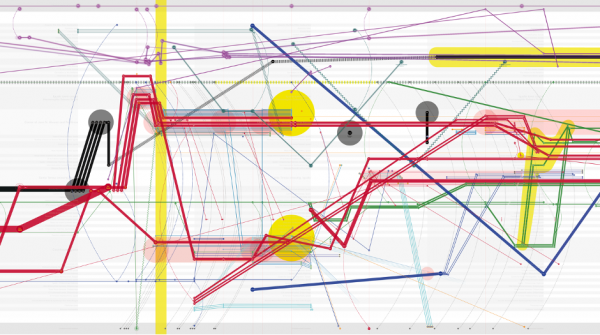

Finally, when there are hundreds of witness testimonies that often contradict each other, such as in the case of the 43 Disappeared Students of Ayotzinapa, Forensic Architecture starts by datamining, extracting spatial and temporal information, tracking the locations of all actors from the hundreds of collected testimonies. By analysing these accounts, we are then able to plot them both on traditional maps and on timelines, studying how the accounts converge and diverge from one another. Through this process, we can observe patterns that reveal State lies. We can also start making out the figurative form of events that rises above the noise.

In the Ayotzinapa case, Forensic Architecture produced a mural (see image below), that plots the narrative trajectories of different participants, both victims and perpetrators, in the forced disappearance of the 43 students. The simplified narrative presented by the Federal Attorney General and announced as the “historical truth” (drawn in thick black line) is contrasted with the complex version derived from the testimonies of the surviving students and those provided by the Independent Group of Experts (GIEI).

The Ayotzinapa Mural, Forensic Architecture, 2017

Concluding Remarks

When perpetrating States obfuscate the events of violence in order to conceal their accountability and create ambient fear amongst the surviving population, civil society’s remaining tool for resistance is the patient and careful reconstruction of what took place. When the perpetrators hide and confuse, we must persistently locate and disentangle. In all of the techniques mentioned above spatial and temporal matrixes offer heuristic tools for the study of broken links caused by the mediatisation of events (either on audio-visual footage or the human brain), as well as the circumscription of the voids in knowledge that escape representation. The precision of this type of analysis is a form of care, that offers human rights defenders a clearer picture, as well as a roadmap and a focusing tool for their political action. For unless we can locate the sites of violence how could we begin to fight against it?

Christina Varvia is currently a Research Fellow and formerly the Deputy Director of Forensic Architecture. She was trained as an architect and has taught at the Architectural Association. She is currently pursuing her PhD at Aarhus University and has received the Novo Nordisk Foundation Mads Øvlisen PhD Scholarship; she is also a Fellow at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art.