Unlikely encounters of international law and technology

An Interview with Valentin Jeutner

Valentin Jeutner’s book [l]ex machina: Unlikely encounters of international law and technology is a collection of international law poetry and international law visual art works that he created with the aid of technology. As any piece of art, it is hard to summarize, but you can see for yourself since the electronic version of the book is available open access (see link above).

Are you turning international law into poetry, or is the poetry already in the international law and you only elicit it?

The poetic quality is embedded in international law itself, I think. None of the different “treatments” that I subjected the texts to created text / images from scratch. Rather, my technique was to engage with conventional international legal instruments – like the UN Charter or the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties – in a manner that reveals something about these texts that is otherwise difficult to spot. Maybe one could compare it to the study of a famous painting – like the Mona Lisa. Some of the [l]ex machina experiments are akin to someone focusing only on a tiny square of that painting (or to someone studying the painting’s frame or back) – allowing you to see that the paint and the canvas which da Vinci used is the same as that used by most of his contemporaries. Such an approach does not capture Mona Lisa’s particular smile, but it does identify the creative intention, the creative acts and choices that went into painting that smile by clearly separating the material aspects of that painting from the author that employed the materials in a particular manner. And this is also, I think, what I wanted to achieve with respect to these international law texts that I experimented with.

You take international law texts and transform them. Can you describe the creative act?

Yes, the creativity involved – my own creativity – varies a little bit across the four different sections of the book. But the most important choice is often the decision concerning the kind of text that I want to use as a point of departure. So with respect to the first section, for example, the one that modifies specific texts – I needed to select a treaty or a case or a list of cases or a book that I wanted to work with. Different texts have different qualities. Some are relatively rich – like transcripts of oral pleadings before the ICJ or the different historic textbooks that I used. Other texts are really challenging to work with – the ICJ’s Rules of Procedure, for example. They are relatively short, they are very technical and they employ a very limited range of words. That makes an interesting creative engagement difficult and it took me a long time to squeeze anything creative out of these rules of procedure. The second creative act concerns the choice of method that I want to apply to a text. For example, I have to decide whether I want to zoom-in on one specific word or whether I want to weave multiple expressions together so that the text tells some kind of a story.

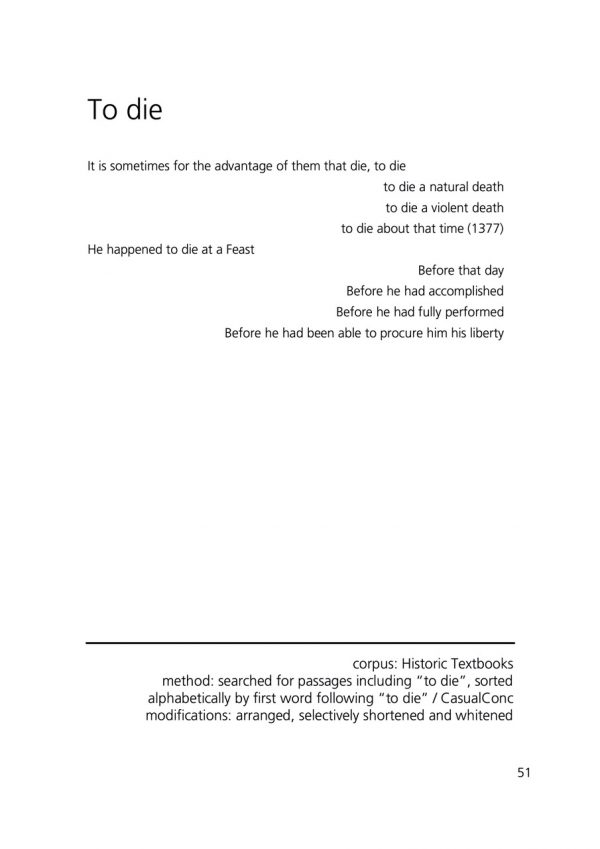

I am interested to learn a bit more about how this process works practically. Take for instance the poems “Once” and “To die”: you chose expressions that appear repeatedly in the legal texts. Were there other candidates that you tried till you chose these expressions as the pillars of the poem?

Sometimes I start reading a text and I notice terms that I feel could reveal something meaningful. If I remember correctly, regarding Sir David Maxwell Fyfe, for example, I wanted to see how the personal pronoun ‘I’ is used in the transcripts of the Nuremberg trials. Similarly, I thought ‘once’ could be a promising term to experiment with for ‘Once’ and ‘Once again’. But this is an organic process. The poem ‘To die’, that you mentioned, came about, for example, because I was actually looking for references to ‘sometimes’ in the historic textbooks. And then I stumbled upon the really intriguing sentence: ‘It is sometimes for the advantage of them that die, to die’ and I thought I should do something with this. And yes, of course, there are many attempts that did not work out – which is also to be expected because international legal materials are a very peculiar text corpus. Often, I envied Hannes Bajohr whose book Halbzeug inspired the [l]ex machina project because he works with much more diverse corpora like speeches of the Bundestag, Fairytales or newspaper articles. For example, I tried to construct a poem about ‘love’ for a few days but none of my text corpora produced any meaningful outcome in this regard. ‘Tea’ also did not work particularly well. So, going back to your first question – the experiments collected in [l]ex machina are not random or created by me freely without regard to the texts – my creative engagements with the texts takes place (literally) on the terms of these texts.

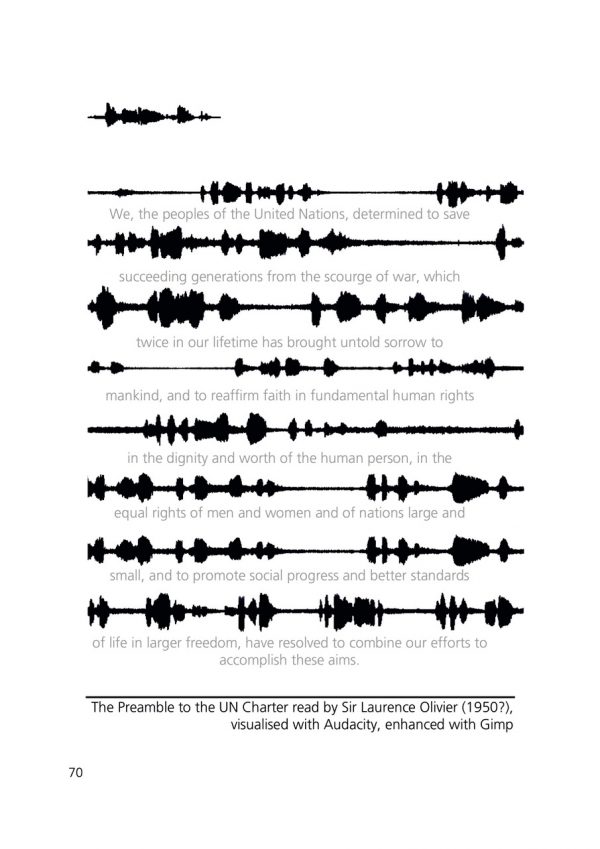

Another example is the visual representation of the sound graph of the Preamble of the UN Charter. How did you get to this idea? Did you picture this graph in your mind before creating it?

I got the idea to visualize the preamble of the UN Charter because I remembered that there used to be a UN website where the recording of Sir Laurence Olivier reading the Preamble to the Charter would automatically start playing and I thought that hearing that recording and hearing clearly that it was quite an old recording added a layer of meaning to the text of the Charter itself. I could not print the recording itself of course. But the soundwaves that I could print still add something to the text itself – they add a human element to it.

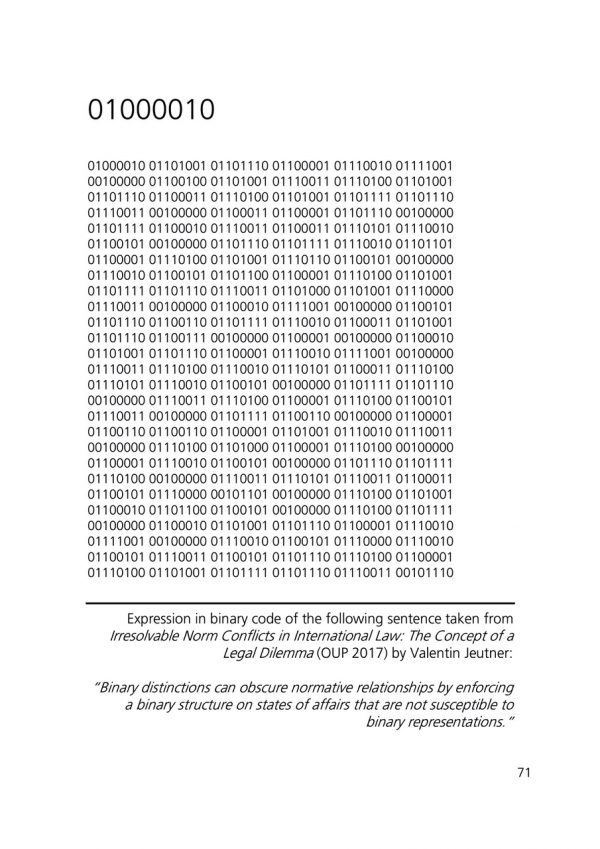

Included in the book is also an expression in binary code from your own book “Irresolvable Norm Conflicts in International Law: The Concept of a Legal Dilemma” (2017). Seeing a sentence from your book in binary code: did anything new about its meaning spring to your mind?

Yes, maybe. Maybe seeing the book’s sentence on binary distinctions expressed in binary code reminded me that binary symbols can be used without subscribing to a practice that endorses slicing up the normative cosmos in a binary fashion into, for example, right and wrong, the east and the west, the rich and the poor. One can think in binary terms without using binary code and one can use binary code without thinking in binary terms. Since I am suspicious of binary thinking, I had intuitively – and probably entirely unjustifiably – also been suspicious of binary codes. But since my binary code translator very faithfully translated my book’s sentence that criticizes binary thinking, I might now look at binary codes a bit more kindly.

Are there broader connections between your previous work and the [l]ex machina book? Is there, beyond the individual beauty of the pages, a message the book conveys?\

[l]ex machina is of course a very specific kind of project and it is not directly connected with my previous publications. But it is connected to my general interest in communicating when writing and, particularly, when teaching that the shape of the international legal order as we know it is the result of particular choices that particular people took at a particular moment in time. In other words: that a different world is possible. There might be good reasons for the current shape of the legal order but there might also be good reasons to question the very foundations of this order. The [l]ex machina experiments try to do this by engaging the literal aesthetic of international law’s scriptures. I think an aesthetic engagement with law, an engagement that speaks to the senses, is particularly good at provoking thoughts, reflections, Nachdenklichkeit, concerning the current state of the law and what it represents.

The [l]ex machina collection is available here. The last ten pages of the booklet explain in some detail how the different text corpora were compiled and which software tools were used.

Dana Schmalz ist wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin am Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht in Heidelberg/Berlin und Stipendiatin der Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung.

Valentin Jeutner is an Associate Professor of Law at Lund University in Sweden. His teaching and research activities focus on foundational question of (international) law.