Humanitarian Visas to Escape from the Taliban?

A Legal Pathway with Low Acceptance

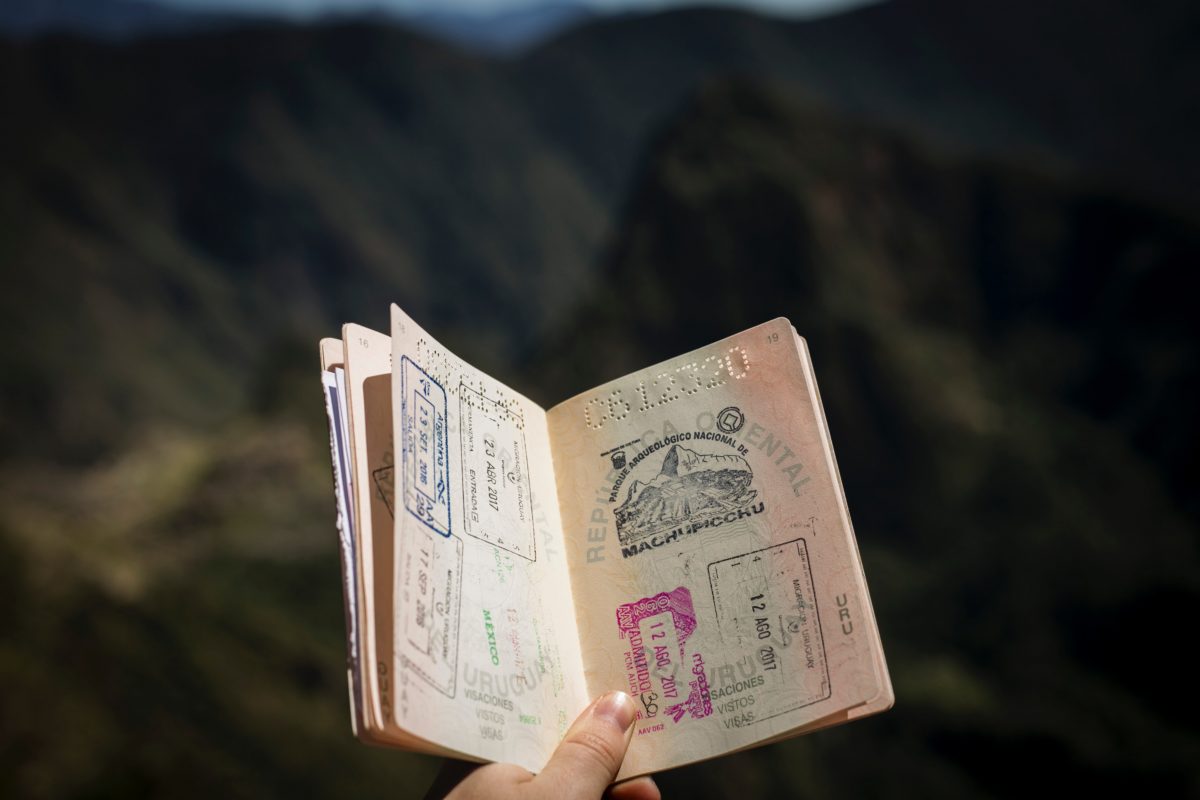

The Taliban’s seizure of power has led to the expectation of a sharp increase in the movement of Afghan protection seekers to countries of refuge. Although the international community tried to evacuate particularly vulnerable people (e.g. interpreters working for Western embassies or armed forces), the vast majority of the Afghan population is more or less left to its own fate in an effort to reach a host-State. Against this background, voices have been raised, requesting States to provide Afghan (especially women) protection seekers with humanitarian visas, so that they can safely approach their territories.

But do European States have an obligation to do so under European or national law? It is precisely this question that this blogpost will address.

The Obligation to Grant Visas under Relevant Jurisprudence

The jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the European Union (‘CJEU’) and of the European Court of Human Rights (‘ECtHR’) seems rather clear on the matter.

The CJEU was given the opportunity to address the issue in X and X v. Belgium, whereby a Syrian family requested humanitarian visas at the Belgian embassy in Beirut in order to flee from the precarious security situation in their home country. In his opinion, Advocate General Mengozzi supported the applicants arguing that Member-States are required to issue such humanitarian visas in light of Art. 25(1)(a) of the Visa Code of the European Union (para. 176 of the opinion). However, in March 2017, the CJEU ruled that the Visa Code of the European Union does not apply to visits of more than 90 days in a 180-day period. As asylum requests usually demand a longer stay in the country of refuge, the CJEU found those requests to be solely justiciable by national law (para. 51). A potential violation of provisions of the ECHR by the decisions of the Belgian authorities had not been addressed by the CJEU.

The ECtHR has dealt with a similar situation in M.N. and Others v. Belgium. Also in this case, a Syrian family had tried to obtain humanitarian visas from the Belgian embassy in Beirut. The applicants claimed that the rejection of their application (or: violated) Art. 3 ECHR (prohibition of torture). Unsurprisingly and following its earlier approach in Banković, the ECtHR declared the application inadmissible (para. 125) and did not proceed to the merits of the claimed violation. Precisely, it admitted the application of public power by the Belgian authorities when deciding about the conditions of the entry into its territory even when the applications are filed abroad (para. 112). However, the ECtHR held that this situation is not sufficient to bring the application into the scope of Art. 1 ECHR (Obligation to respect Human Rights [para. 112]). In their reasoning, the judges also referred to the above-mentioned judgment of the CJEU and stressed the non-applicability of EU law to the actually requested visas (para. 124). Nonetheless, the ECtHR clarified that “this conclusion does not prejudice the endeavours made by the States Parties to facilitate access to asylum procedures through their embassies and/or consular representations” (para. 126).

As indicated above, both decisions deny the right of asylum seekers to obtain humanitarian visas with different justifications. While the CJEU does not recognise a positive obligation to issue humanitarian visas under current EU law, the ECtHR bypassed a closer examination on the merits of the case by declaring the application inadmissible. Instead, both courts apply a more formal approach and omit a deeper insight into the cases under the principles of international law. To reach this conclusion, the courts seem to have been influenced by the motive to avoid potential factual implication that a different finding would have (e.g. embassies being overrun by asylum seekers wishing to obtain humanitarian visas).

The Obligation to Grant Visas Under National Law

In view of the two decisions, the issuance of humanitarian visas lies in the discretion of the States and the relevant national law. Currently, only the Russian Federation and Switzerland have created explicit regulations on this type of visas in their national legislation.

Precisely, according to Art. 25.6 of the Federal Law No. 114-FZ of August 15, 1996 on the Procedure for Exiting and Entering the Russian Federation “a visa for entry into the Russian Federation for the purpose of asylum shall be issued to a foreign citizen for a term of up to three months if there is a permit of the federal executive governmental body in charge of internal affairs to deem this foreign citizen a refugee in the territory of the Russian Federation”. This requires the refugee to first lodge an application with the Russian diplomatic mission or consular office to be issued a certificate recognising him as refugee. The mission or office performs a preliminary examination of the application in accordance with Art. 4 para. 5 subpara. 1 of the Federal Law No. 4528-1 of February 19, 1993 on Refugees and issues its decision within one month. If accepted, all documents are submitted within five days to the relevant territorial authority in Russia, where the requested certificate is then issued and sent to the mission or office (Art. 4 para. 6 of the before mentioned Federal Law). The necessary visa may be issued only from this moment on. There is no reliable statistics available as to how many visas of this kind have been issued in the last few years.

Until September 2012, Swiss missions abroad were even authorised to receive asylum applications. Since that time, only applications for humanitarian visas can be logded there. According to Art. 4 para. 2 of the Ordinance of the Swiss Federal Council on Entry and the Issuance of Visas, to obtain a visa this way, an asylum seeker needs to prove that s/he is in direct, serious and concrete danger to life and limb in the country of origin. In 2019 only 172 and in 2020 only 66 humanitarian visas were issued in this way. In 2018, the office of UNHCR for Switzerland and Liechtenstein raised concerns about an official instruction that an asylum seeker had to file the application in a Swiss mission in his country. Following the escape of many Afghan nationals to neighbouring countries (especially to Uzbekistan and Pakistan) this instruction has been amended in September 2021 to allow asylum seekers to apply in Swiss missions in these countries. Still, the same instruction notes that if the asylum seeker is already in a third country, it can usually be assumed that there is no longer any danger for him according to Art. 4 para. 2. Given the strict practice of obtaining humanitarian visas by Swiss missions and the traditionally very low numbers of approved applications only a handful Afghan nationals will probably be privileged to receive asylum in Switzerland.

Some non-member states of the Council of Europe have initiated programmes to bring Afghan refugees to safety via visas. The Department of Home Affairs of the Australian Government (DHA) offers the legal possibility to apply for a so-called Subclass 202 Global Special Humanitarian visa if a foreign national faces substantial discrimination or human rights abuses and have a proposer for this purpose though the decision process could take many months or even years. Specially for Afghan nationals, the Australian Government announced in August 2021 to provide 3,000 humanitarian places and promises to afford them visa processing priority. In fact, by 15 November 2021 not a single humanitarian visa has been granted by Australia out of this quota.

Conclusion

For most Afghan nationals wishing to flee from the Taliban regime, it remains more a dream than reality to get to Europe legally. As both the CJEU and the ECtHR leave it to individual Member-States of the respective treaties to create national regulations for the issuance of humanitarian visas, nothing is developed to present those refugees a safe way out of their difficult situation. The Russian Federation and Switzerland will not be willing to take in many asylum seekers this way, while other European States remain passive. The new Danish law on the transfer of asylum seekers to (safe) countries outside the EU symbolises the unwillingness of Member-States to host refugees even if they have already arrived on the territory.

Also, the EU bodies don’t seem to undertake many actions to facilitate the issuance of these kind of visas. More than just a resolution by the European Parliament (EP) to provide Afghan women with humanitarian visas (para. 40) and to urge the Commission to publish a legislative proposal for humanitarian visas in general (para. 41) has not been raised in this respect yet. Instead, in the same decision, the EP stresses that it will support countries like Uzbekistan (at para. 44) with financial means. The purpose is obviously to keep Afghan refugees as from Europe as possible. A similar situation is already in place with Syrian refugees in Turkey supported with billions of Euros by EU to enable at least some minimum living conditions for them.

The “Bofaxe” series appears as part of a collaboration between the IFHV and Völkerrechtsblog.

Ilja Djatschkow is a PhD candidate at the Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict (IFHV), Ruhr-University Bochum. He practices as lawyer (Rechtsanwalt) in the field of Dispute Resolution at the Cologne office of the law firm Deloitte Legal.