99’000 disappeared and counting

The tale of enforced disappearances in Syria

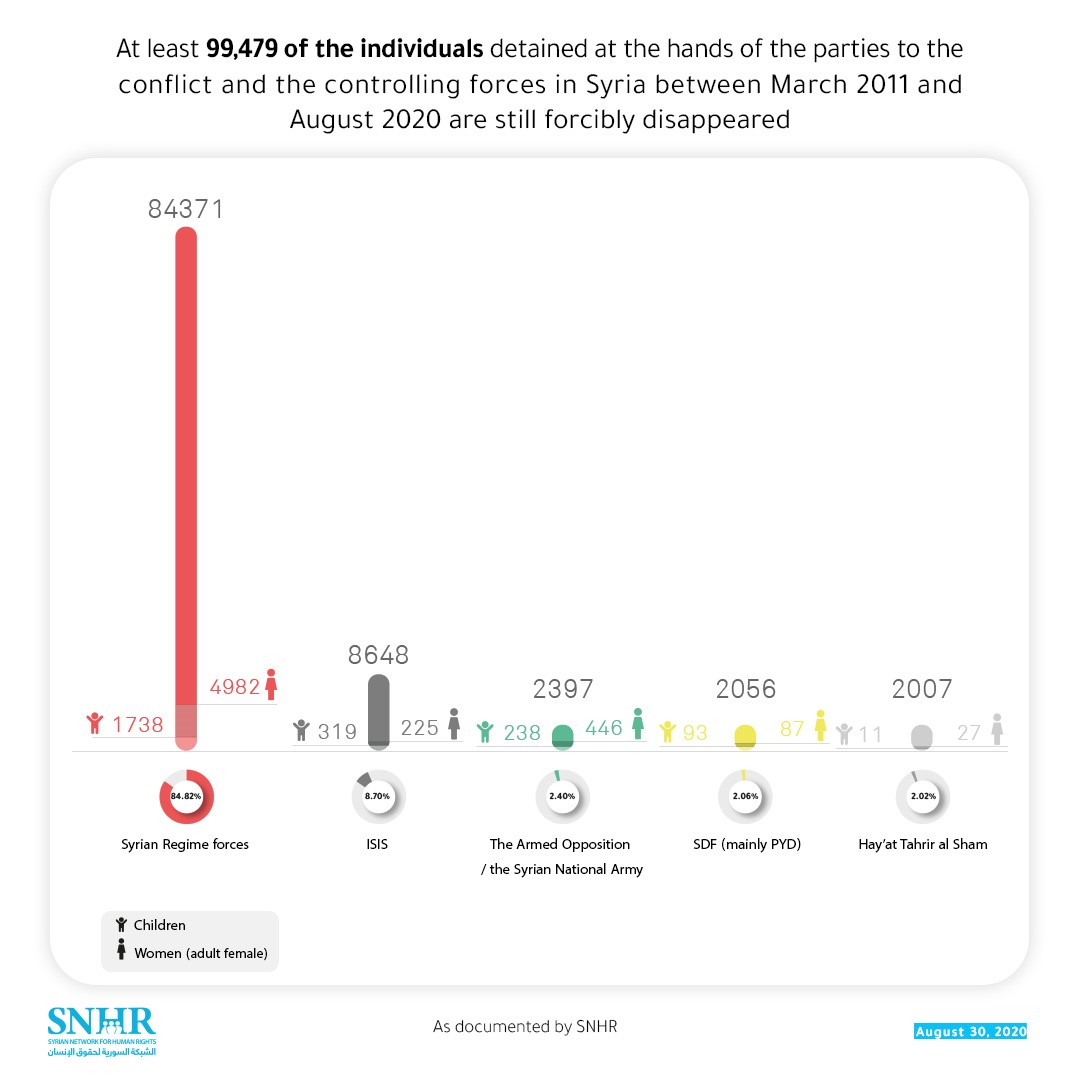

It is estimated that about 1.2 million Syrian citizens have been arrested and detained at some point since March 2011. During this period, an estimated number of 99 000 persons have been forcibly disappeared, while the Syrian Regime is responsible for about 84 000 of these cases (SNHR Report of 30 August of 2020, p. 8, 9).

The crime of enforced disappearance, which is often accompanied by acts of torture, violates international law. The Syrian Arab Republic is not a party to the 2006 International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED). However, the prohibition of enforced disappearances flows also from customary rules of international humanitarian law, when taking place within an armed conflict, as well as from the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Syria has ratified.

While enforced disappearances are not specific to the Syrian armed conflict and are in fact a common feature of many armed conflicts, the sheer number of enforced disappearances sets Syria apart, especially when compared to the total population of Syria (21 million at the start of the popular uprising in 2011). Assuming that each forcibly disappeared person has at least five family members or friends, nearly half a million individuals are directly affected by the crime of enforced disappearance, i.e. nearly 0,3 % of the total population. This very high percentage has a terrifying effect on the Syrian society as a whole.

As the chairman of the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), I have been working for the last ten years on enforced disappearance in Syria. Since the beginning of the conflict, the SNHR has been gathering information on enforced disappearances. We have noted that these crimes are being used as a weapon of war in the Syrian conflict, mainly, though not exclusively, by the State forces. Through our continuous work, we have identified some main characteristics of enforced disappearance in Syria, which can be summarised as follows.

First: The arrests themselves are arbitrary and are more akin to kidnapping

The majority of arrests in Syria are executed without a judicial warrant (SNHR Report of 2 December 2020, p. 2). These arrests are considered arbitrary, as the arresting individuals do not identify themselves, and do not inform the citizen of the arrest’s reason. The detainee is not informed about the location of the detention and is not allowed to contact his or her family. The context of these arrests is mostly the passing of the victims through checkpoints or during raids (ibid, p. 2). In fact, the security forces of the Regime’s four main intelligence services are often responsible for extra-judicial arrests (SNHR Report of 30 August 2020, p. 2). Our estimates suggest that nearly 131,000 individuals are still detained or forcibly disappeared by the Syrian Regime (ibid, p. 13).

Second: The Syrian Regime is responsible for the largest proportion of the disappeared

The Syrian Regime is responsible for nearly 89% of all cases of arrests and detentions (SNHR Report of 2 December 2020, p. 2), and thus constitutes the leading conflict party in systematically committing this human rights violation (Independent International Commission on Inquiry on the Syrian Arab republic, Report of 3 February 2016).

Additionally, as the Syrian Regime did not open any investigation over the past ten years into this kind of incidents perpetrated by its allied forces (including Iranian militias, the Lebanese group Hezbollah), these militias might also have felt encouraged to arrest, torture and to forcibly disappear detainees, at the checkpoints that they had set up across the Syrian-Lebanese borders (SNHR Report of 2 December 2020, p. 19). This absence of investigations constitutes in fact a green light for the militias to continue these violations.

The other parties to the conflict and the controlling non-Regime forces in Syria, such as the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, extremist Islamist groups, and various Armed Opposition factions, use similar strategies and practices as the Syrian Regime, albeit at a much lower rate and in a less systematic manner (Independent International Commission on Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, Report of 8 March 2018).

None of the parties to the conflict or the controlling forces provide the community with any public record showing the whereabouts of the arrested / detainees and the reasons for their arrest; nor do they provide any documentation of the judicial sentences issued against them, including the death penalty (Amnesty International, Report 2017). Most of detainees’ families do not know the fate of their loved ones, as the SNHR has indicated in its monthly reports as well its thematic reports on arrest and enforced disappearance.

Third: More than 70% of the detainees are forcibly disappeared

As stated previously, the arrests are carried out by non-identify persons and in many cases, the detained persons are not enabled to communicate with their relatives or lawyers. Furthermore, the State authorities deny the arrests they have carried out (SNHR Report of 2 December 2020, p. 2). Due to this refusal to acknowledge the deprivation liberty, and thus in accordance with article 2 ICPPED, the SNHR categorizes 70% of the total number of these detainees as forcibly disappeared.

Most of the detainees, around 85%, are political detainees, while the other 15 % are armed opposition fighters (SNHR Report of 15 October 2020, p. 9). They were arrested in the context of their peaceful participation in the protests as “human rights activists, media workers, medical personnel, aid workers, opposition party members, opinion writers” or social media activists (ibid, p. 9).

Fourth: The detainees are subjected to brutal torture

According to a special report issued by the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, detainees are subjected to brutal methods of physical and psychological torture, with hardly any detainees being able to escape these inhuman treatments (Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, Report of 3 February 2016, para. 22). Detainees confess under torture to crimes they had no connection to, but their confessions are recorded and retained within reports in the Regime’s security branches (SNHR Report of 15 October 2020, p. 9). Irregular courts established by the Syrian Regime rely on these reports when indicting the detainees referred to them. However, only 20% of the total number of detainees are actually referred to these irregular courts, while the others are waiting to be charged for up to 8 to 9 years (ibid, p. 9).

As SNHR, we assume that the acts of torture continue against the forcibly disappeared throughout the duration of their detention and that this is still practiced since we constantly receive information about the deaths of persons registered in our database as forcibly disappeared.

Fifth: Exceptional challenges in documenting cases of arrest or enforced disappearance

The families of the disappeared are often reluctant to cooperate or provide details on their relatives’ arrest (even confidentially), especially if the arrested individual is female (SNHR Working Methodology, p. 15). This reluctance is due to the widespread and justified fear in Syrian society that the discovery of the cooperation could lead to more torture and danger for their loved one(s) and themselves. Instead, families often try to negotiate with the security forces of the Regime. However, these often blackmail the families and demand ransoms, which in some cases can amount to thousands of dollars (ICTJ Policy Paper, p. 10). In result, the relatives’ reluctance to cooperate adds additional challenges to the cases’ documentation (SNHR Working Methodology, p. 15).

The failure of the international community to apply any real pressure on the Syrian regime authorities to release detained individuals (including those whose sentences are completed) has also led many Syrians to believe that it is useless to cooperate in the documentation process (SNHR Working Methodology, p. 15).

However, without the cooperation of families, SNHR cannot continue the documentation of these cases. It is very difficult to convince them to cooperate, when we cannot offer them any hope, or any information about the fate of their children.

Despite these challenges, the SNHR has created complex electronic programs in order to collect, verify, categorize and archive the detainees’ data (SNHR Working Methodology, p. 17). This collection of information has thus made it possible to classify by gender, the place of their arrest, the governorate of origin, as well as the conflict party responsible for the arrest. These programs also allowed us to analyse and to compare the data, for example to identify the governorates with the highest proportion of residents arrested and disappeared.

To document these arrest incidents and disappearances, we have published periodic news reports, monthly reports, and other special reports related to detainees over the years. Periodically, we submit special forms to the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (WGEID), the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention and the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture.

Outlook

As SNHR, we believe that if the current Syrian regime continues in power, there will be no real disclosure of the fate of the forcibly disappeared in Syria, whose numbers have multiplied dozens of times. In our view, the only way to end this would be through a political transition in accordance with UN Security Council resolutions. We are convinced that this is the only option to ensure that the Syrian people can have a government that upholds democratic values and respect for human rights, finally bringing the long-awaited relief form the suffering of their families. I personally hope to see that day soon.

Fadel Abdul Ghany is the founder and chair of the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR). He wrote opinion articles and participated in research projects with local, regional, and international organisations.