Welcome to the latest interview of the Völkerrechtsblog’s symposium ‘The Person behind the Academic’! With us we have Prof. Noëlle Quénivet, and through the following questions, we will try to get a glimpse of her interests, sources of inspiration and habits.

Welcome Prof. Quénivet and thank you very much for participating in our symposium!

May I first ask what it was that brought you to academia and what made you stay?

Originally, I wanted to work in humanitarian assistance. Towards the end of my LL.M. I applied for jobs but was told I was too young. In fact, most posts required applicants to be 25 years old and I was 22. So, I had to ‘entertain’ myself for another three years! I did internships at the Council of Europe and UNHCR and then enrolled in a PhD programme. I wanted to return to France but that was not possible and so stayed in the UK. And then the PhD became a problem: over-qualified! My first post was a six-month part-time contract as a research assistant at the Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict at the Ruhr University of Bochum in Germany. I stayed there for four years and absolutely loved every single bit. I was teaching amazing students, researching and publishing in fields I adored, travelling around Europe and the world to teach and train engaged participants, working with fantastic colleagues, etc. However, my position was precarious, and I thus moved back to the UK to become a Senior Lecturer. I stayed in academia because that’s what I am good at and I enjoy most aspects of the job.

Which factors raised your interest in the protection of women and children in armed conflicts?

My interest in the law of armed conflict is a convergence of a fantastic course in international humanitarian law in the LL.M programme at the University of Nottingham, a father who spent his youth in the armed forces and was in the French armed forces reserve, and a grandmother who recounted to me how she and her family survived two world wars. As for my interest in sexual violence and women in armed conflict, you have to blame Michael J. Fox for it! As a teenage fan I went to see ‘Casualties of War’ (I was the only person in the cinema!) and was really shocked by it. Two topics featured in my PhD applications: the prosecution of rape as a war crime and the recognition of rape as an act of persecution under the Refugee Convention. You see the link… As for my interest in children in armed conflict, it all stems from a discussion with a colleague at my current institution who specialized in children’s rights as we were thinking of co-authoring a paper. The result was a book chapter on girl child soldiers. The beginning of a long story.

If you were not an academic, what would you be?

I would have loved to become a novel writer or a journalist. As a teenager, I consumed an insane number of books, mostly the classics of French and German literature. I loved reading and writing. After all, that’s what I am doing now!

What is your greatest disappointment with international law? And in which way(s), do you think that international law is wrongly criticized?

I am not disappointed with international law. After all, it is the law of the States with a push from a variety of other actors and especially international organisations. It is as good as the States want it to be and the other actors are able to persuade States to change the law and their behaviour. An excellent illustration of how various actors have effectuated positive change is the Ottawa Convention on anti-personnel landmines.

International law is often wrongly criticized for its lack of enforcement. How often do I hear that it is useless law! And, in international humanitarian law, the classic comment I get when I teach it is ‘it is a nice set of moral principles, but no one applies it’ followed by a litany of examples from Kosovo to Afghanistan. Of course, we always focus on the instances of violations of international humanitarian law and not on the acts of compliance. Ever heard of military legal advisers advising against targeting a specific object? No, unless you have the chance to meet them and, as they describe their jobs to you, it becomes obvious that they ensure the law is complied with. Also, this focus on non-compliance is found in other fields of law: do we spend a lot of time discussing instances when someone is not murdered? No.

What is your favourite place to read and write? What is always near you when you read and write?

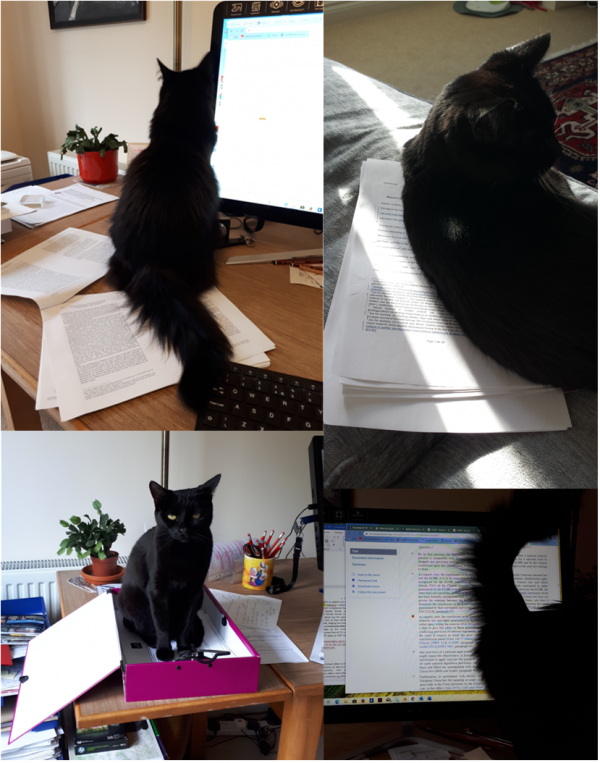

My favourite place to read is my bed. I need to be in a place where I can relax and let my brain run free. In front of the computer, I am too focused and tense to be able to link ideas and there is always the temptation to reply to an incoming email. I always have a highlighter to go through the most important sentences and sections and a pencil to add comments and specify in which section of my own work I need to refer to this argument or idea. Judgments are however read on the screen. They are too long to be printed! Writing, on the other hand, is carried out sitting on my chair in front of the computer, a pile of papers sitting on the left (the papers whose ideas I need to integrate into my own paper) and a pile of papers on the floor (the papers I have fully exploited/explored). I have occasional helpers who believe that journal articles are cushions, pencils are things to chew on, screens are useful to highlight the beauty of their tails, etc.

[Picture taken by Noëlle Quénivet and sent to us with regard to this question.]

What is an energy and inspiration booster, at times when you have none?

After a long day of work, I enjoy not only cooking but also reading cookbooks. Whilst pursuing an LL.M in Nottingham, I lived in shared on-campus accommodation and befriended three young women from India, Singapore and Japan. We spent most of our time in the kitchen and they taught me the basics of Asian cuisine. I bought my first cookbook in an Asian shop and have since then accumulated nearly 350 of them! If you see me on Teams or Zoom, bear in mind that the books behind me are all cookbooks.

[Picture taken by Noëlle Quénivet and sent to us with regard to this question.]

Which of your publications is your favourite one? And which of them is your least favourite?

I don’t really have a favourite publication, but I would say that I am most proud of my book on Sexual Offences in Armed Conflict and International Law, not so much because I think it has great content (I would hate reading it after so many years) but because of the process. My PhD viva was an unmitigated disaster. I ended up rewriting my whole thesis in a year whilst working full-time. Lovely colleagues in Bochum supported me in the process and the external examiner had provided me with pages and pages of outstanding comments. I was absolutely chuffed when I was awarded the Honorable Mention by the American Society of International Law’s Francis Lieber Prize. After all, I was able to write something decent!

If you could, which unspoken rule of academia would you instantly erase?

The unspoken rule I would have instantly erased two decades ago was the grey 3-piece suit that every male colleague in continental Europe wore at a conference. I am so glad this has gone!

Have you experienced or witnessed discrimination in academic circles? What do you think would help lessen discriminatory instances in academic circles?

When I was an early career researcher, it was quite rare to see women specialized in the law of armed conflict and we were certainly not trusted to know anything on the topic. I noticed this on several occasions. For example, as I was about to start a course in international humanitarian law to be delivered to professionals, a group of men stood up, packed their stuff and left the room! I was told I was not the ‘type’ of lecturer they had expected. They came back the next day as other participants had told them that they had learned a lot in the session. On another occasion, I was invited to present a paper at a workshop with well-known experts. Whilst I was chatting to the only other female speaker, one of the presenters looked at me, told me to get him a cup of coffee and left. I stood there not sure what to do whilst my female companion was muttering under her breath. There were numerous instances where I felt I was not trusted to do the job. The way I dealt with it later was simple: I would introduce myself by listing all the courses I had taught, the papers I had written, etc. (I know it sounds vain but at the time it was the only mechanism I found to tell the audience I knew what I was talking about! I don’t do that anymore…) and when I was in Germany, as strongly suggested by the wonderful secretary of the institute, I began the presentation by stressing the ‘Frau Dr’.

What are you working on currently? What may we anticipate in the near future?

I am currently writing a book on International Law and Child Soldiers for Edward Elgar’s series ‘Principles of International Law’. It covers everything from the definition of a child soldier to the prosecution of child soldiers and has two case studies: one on child soldiers in Africa and another on child terrorists. It is a challenging and time-consuming project, but I love it as it gives me the opportunity to examine in detail all facets of the topic.

The other big project is a set of articles I am co-writing with the co-author of the book Child Soldiers and the Defence of Duress under International Criminal Law. We presented a paper at a conference on Ongwen and ended up with so much material that we are now looking to publish three separate papers! It has always been a ‘problem’ in our collaboration. Years ago, he sent me an email asking whether we could write a quick paper together as we were both writing on the subject of the prosecution of child soldiers. That paper became a book!

Thank you very much Prof. Quénivet for participating in our symposium and for having taken the time to respond to our questions!

Noëlle Quénivet is Professor in International Law at the Bristol Law School of the University of the West of England (UK).