A New Liability Frontier?

Unilateral Seabed Mining and the Common Heritage of Mankind

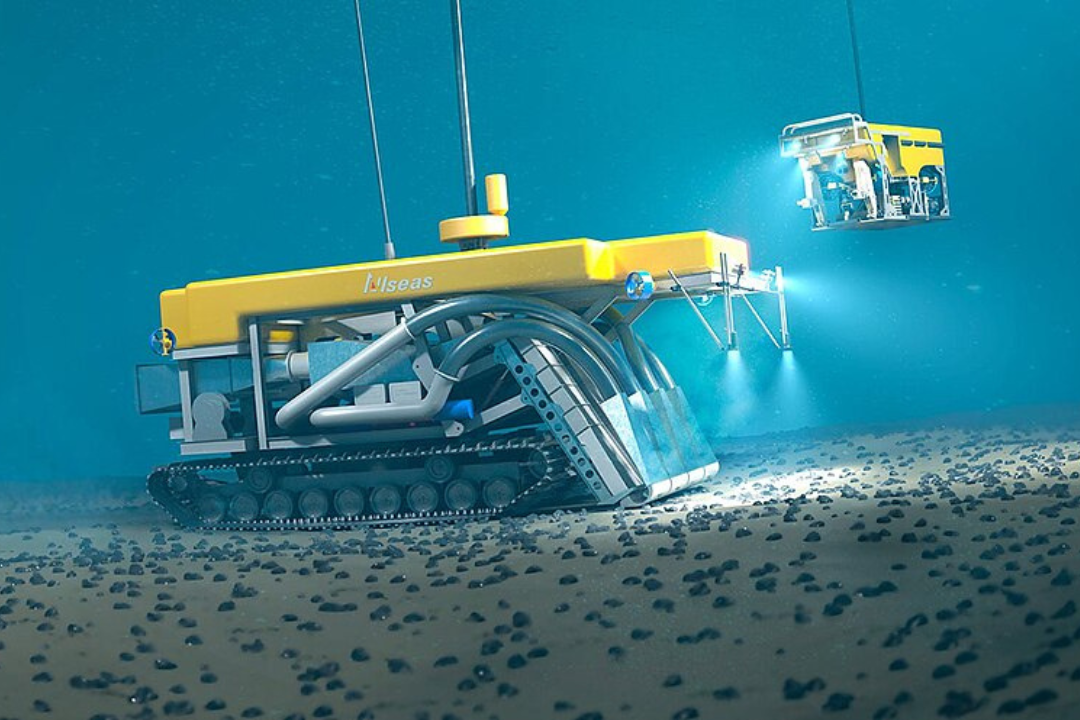

On 24 April 2025, the United States (U.S.) White House issued an Executive Order titled “Unleashing America’s Offshore Critical Minerals and Resources” (the Executive Order) aimed at accelerating the development of seabed mineral resources both within and beyond U.S. jurisdiction. Among its key provisions, the order directs the Administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to “expedite the process for reviewing and issuing seabed mineral exploration licenses and commercial recovery permits in areas beyond national jurisdiction under the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act” (DSHMRA) (Sec. 3(a)(i)). Just five days later, on 29 April 2025, The Metals Company USA — a subsidiary of the Canadian mining firm The Metals Company (TMC) — submitted an application for a commercial recovery permit under DSHMRA, marking the first concrete step toward unilateral deep seabed mining (DSM) activity in the Area by the U.S.

This move has prompted swift international backlash. Nearly 40 States supported the statement of the Secretary-General of the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which argues that any activity in the seabed beyond national jurisdiction (the “Area”) must be carried out under the ISA’s supervision and control. Unilateral action, they contend, constitutes a violation of international law — specifically, of the common heritage of mankind principle.

The legality of the U.S. measure has already been examined in a number of blog posts (here, here and here). This post builds on that discussion by shifting the focus to the question of international liability. Specifically, if the United States proceeds with deep seabed mining outside the ISA framework, could it incur legal responsibility for violating the common heritage of mankind principle?

The Common Heritage of Mankind Principle

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS or the Convention) declares that the mineral resources of the Area are the Common Heritage of Mankind (CHM) — a principle that entails a specific legal status for the Area (UNCLOS, Art. 136).

When applied to the Area, the CHM principle carries six core elements:

- Non-appropriation/non-acquisition,

- Vesting of rights in humankind,

- Reservation for peaceful purposes,

- Environmental protection,

- Equitable sharing of benefits, and

- Governance via a system of common management

However, when it comes to the specific obligations that these elements entail, it is important to distinguish between CHM as a treaty-based principle under UNCLOS and CHM as a principle of customary international law.

Under UNCLOS, the obligations arising from the CHM principle are set out in Part XI. The legal regime governing the Area set out in Part XI of UNCLOS is further supplemented by the 1994 Agreement Relating to the Implementation of Part XI and the Mining Code, a comprehensive set of rules developed by the ISA that governs commercial exploration and exploitation of deep seabed minerals. The rules on exploitation are being developed. Under UNCLOS, the ISA has the sole authority to organize and control activities in the Area and has the obligation to administer its resources for the benefit of mankind as a whole (UNCLOS, Art. 157(1) and 140(1)).

UNCLOS is widely ratified, with 170 parties (169 States and the European Union), the United States being a notable exception. However, the U.S. has signed the 1994 Agreement. It also served as a provisional member of the ISA from 1994 to 1998 and has continued to participate as an observer state. Indeed, for decades, the U.S. had predominantly acted as a de facto supporter of the UNCLOS framework. This means that the U.S. is bound by the CHM principle to the extent that this constitutes a customary norm and has the obligation to refrain from acts which would defeat the object and purpose of the 1994 Agreement (VCLT, Art. 18).

A number of blog posts have already established why CHM has attained the status of customary international law (here, here and here). As this reflects the majority view, this blog post will assume this position and examines the potential international liability the United States may incur for breaching its obligations under the CHM principle, should it proceed with deep seabed mining activities unilaterally. Under international law, a State incurs international liability when it commits an internationally wrongful act attributable to it and in breach of an international obligation (ARSIWA, Art. 1 and 2). In the context of the recent U.S. Executive Order, beyond the threshold question of whether unilateral action outside the ISA framework amounts to such a breach, two specific obligations are particularly relevant:

- The obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment; and

- The requirement to ensure the equitable sharing of benefits derived from activities in the Area.

This post examines whether a violation of these obligations could give rise to legal consequences under international law.

Protection and the Preservation of the Marine Environment

The obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment lies at the heart of the CHM principle as applied to the Area. Under UNCLOS, this obligation is expressly codified in a number of provisions (most notably Art. 145, 192, and 209), and applies not only to States Parties but also to contractors and the ISA. The ISA has the obligation to adopt appropriate rules, regulations, and procedures to prevent damage to the marine environment from activities in the Area (Art. 145). All actors involved in activities in the Area must ensure that their activities are carried out with due regard for environmental protection. This obligation is one of due diligence, meaning that States and entities must adopt all necessary legislative, administrative, and technical measures reasonably expected of them in light of current scientific knowledge and technological capabilities.

Beyond its treaty-based foundation in UNCLOS, the obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment has increasingly been recognized as a principle of customary international law, including in the context of the CHM. The UN General Assembly Resolution 2749 (XXV), sets out that States have the obligation to appropriate measures for and shall co-operate in the adoption and implementation of international rules, standards and procedures for the prevention of pollution and contamination, and other hazards to the marine environment, including the coastline, and of interference with the ecological balance of the marine environment and the protection and conservation of the natural resources of the area and the prevention of damage to the flora and fauna of the marine environment (para. 11).

However, the exact content and scope of the obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment as a general customary international law norm is unclear. In determining this, of assistance are other principles of international environmental law that have attained customary status, such as the precautionary approach (Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay, para. 164; see also 1992 Rio Declaration, Princ. 15; Advisory Opinion on Obligations of States in Respect of Climate Change, para. 293-294) to conduct an environmental impact assessment (EIA) (Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay, para. 204), the obligation to cooperate for the protection of the environment (Advisory Opinion on Obligations of States in Respect of Climate Change, para. 301; Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay, para. 81)

The U.S. itself has acknowledged the customary nature of the environmental protection norm, notably in its broader international environmental law engagements, and has repeatedly underscored its importance in multilateral fora.

To begin with, there are some commonalities between the DSHMRA and the UNCLOS framework. Both the DSHMRA and UNCLOS impose the obligation to protect the marine environment and entail that DSM should not be conducted in areas where it would result in a significant adverse impact on the environment (UNCLOS, Art. 145; DSHMRA, Sec. 103). Like UNCLOS, DSHMRAR also entails the obligation to conduct an EIA (DSHMRA, Sec. 105), establishment of stable reference areas/impact zones and furthering of scientific research.

Nonetheless, major divergence remains between the DSHMRA and the ISA framework. For example, the DSHMRA restricts activities where these would cause damage to the marine environment and does not include the precautionary approach or best environmental practices which extend such protection even to situations where the uncertainty of risk exists. Even the obligation to conduct an EIA is different with UNCLOS requiring more detailed requirements.

These divergences do not, in themselves, constitute a breach of the CHM principle. In theory, the U.S. could impose environmental standards on contractors that are equal to — or even more stringent than — those established by the ISA, using its own administrative and contractual mechanisms. If the U.S. were nonetheless to only comply with the requirements set in the DSHMRA, it is unlikely that it would meet its customary law obligations to protect the marine environment.

Equitable Benefit-Sharing

Probably the most overlooked aspect of the recent Executive Order is the obligation to ensure the equitable sharing of financial and other benefits derived from DSM. This requirement lies at the very heart of the Common Heritage of Mankind principle and has long been the primary source of U.S. resistance to Part XI of UNCLOS — making it unlikely that the United States would voluntarily comply with it.

Under UNCLOS, financial and other economic benefits derived from DSM must be equitably shared among all States through a non-discriminatory mechanism to be established by the ISA (UNCLOS, Art. 140(2), 160(2)(f)(i), and 162(2)(o)(i)). The institutional framework envisioned by UNCLOS has yet to be established. Without it, the mining code will not be complete. The ISA has so far considered a number of models and proposals, but it has not adopted one yet (see here).

However, the absence of an implemented framework does not mean that no benefit-sharing obligation exists. The broader obligation to share equitably benefits derived from activities in the Area has been recognized in a number of UN General Assembly resolutions (Res 2749 (XXV), para. 1; Res 48/263, para. 11) and has even been recognized by the U.S. both in the DSHMRA (Sec. 403 and Sec. 3(a)(2), respectively), and the Executive Order (Sec. 3(B)(c)(ii)). Arguably, this obligation should entail both financial and non-financial benefits.

If the U.S. were to proceed with mining and retain all financial benefits for itself, it would breach the CHM principle as a rule of customary international law, irrespective of whether a treaty-based mechanism exists. The U.S. could — in theory — satisfy its customary obligation by cooperating with the ISA in good faith by establishing an international fund that would benefit all States (for example, a special sustainability fund), or developing its own benefit-sharing scheme. These options may be politically inconvenient but are far from impossible.

Conclusion

Under the Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, a breach of an international obligation by a State, resulting in damage, gives rise to liability. In this case, the damage would stem from the following:

- All the resources of the Area are vested in mankind as a whole. If the U.S. exploits the Area unilaterally, other States and future generations would be affected, resulting in a loss for humanity as a whole.

- DSM could cause irreversible damage to the marine environment and affect other legitimate users.

- The financial benefits from such mining would be unequally distributed, contrary to the CHM element of benefit-sharing, depriving other States of the returns.

Even though these actions could, in principle, give rise to international liability, enforcement remains elusive. Still, the lack of enforcement does not erase the underlying legal obligations. If the CHM principle is to remain meaningful, benefit-sharing and environmental protection cannot be optional. This brings to the forefront the obligation imposed on UNCLOS Member States not to recognize or support U.S. claims over the Area and in such a way safeguarding the UNCLOS framework.

Tajra Smajic is a PhD candidate at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, specializing in the governance of deep seabed mining. Through her work, she aims to explore and address the complex legal challenges at the intersection of law of the sea and other areas of international law.

Gustavo Leite Neves da Luz holds a PhD in Law from the University of Hamburg. Specialized in international procedural law, international environmental law, and the law of the sea.