Recently, the Principality of Liechtenstein brought an inter-state complaint against the Czech Republic to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). Already before, the two countries shared a complicated relationship. Due to an unsettled dispute, the two States recognized each other only in July 2009. The same dispute – which essentially concerns the expropriation of Liechtenstein nationals after the end of the Second World War – is also the subject of the current procedure before the ECtHR. The complaint joins a number of more recent inter-state complaints which have been considered as a ‘renaissance’ of this form of procedure. Just this summer, a further state complaint was referred to the ECtHR: The Kingdom of the Netherlands lodged an application against the Russian Federation. The subject of the proceeding is the downing of flight MH17 over Ukraine in 2014. According to a joint (international) investigation team, there is evidence indicating that the civilian aircraft was shot down by a Russian BUK surface-to-air missile.

Our advisory board member Isabella Risini researched both cases and is an expert on inter-state applications before the ECtHR. We had the chance to talk with her about the current procedures, as well as on the ‘renaissance’ of the inter-state application.

In Janowiec and Others v. Russia, the Court held that facts that occurred prior to the ratification of the Convention only fall within the temporal scope of the Convention if there is a genuine connection between the original event and the entry into force of the ECHR (para. 127 et seq). Isabella, do you think that Liechtenstein’s reference to the recent decision of the Czech Constitutional Court will convince the ECtHR that this criterion is met – even though the original measures date from 1945/46?

I had the privilege to see a summary of the application and it is indeed correct that Liechtenstein focuses on the decision rendered by the Czech Constitutional Court in February 2020. So, predictions are always marked by uncertainty. However, the proceedings leading up to the Constitutional Court’s decision fall within the temporal scope of the Court’s jurisdiction, since these events unfolded since 2014 and thus took place after the ratification of the ECHR by the Czech Republic. Therefore, I think that the case will move forward to the merits stage.

I would assume that Liechtenstein is trying to not run against the same wall it did in the Certain Property case. While the case has to be distinguished from the current proceedings, the ICJ turned down Liechtenstein’s claims for the lack of temporal jurisdiction. Liechtenstein used the European Convention on the Peaceful Settlement of Disputes of 1957 as jurisdictional basis. The subject of the dispute – which essentially concerned as well an expropriation in the aftermath of 1945 – took place before the Dispute Settlement Agreement came into force in 1980. Liechtenstein, which is advised inter alia by former ECtHR-judge Mark Villiger, certainly will be well aware of jurisdictional limitations and potential risks inherent in the Strasbourg proceedings.

How the Court will then deal with the rather complex context of the case remains to be seen. Possibly, if the Court finds the case to be within its jurisdiction and admissible, there may be room for a friendly settlement.

In the case of flight MH17, the extraterritorial responsibility of the Russian Federation will most likely be a central aspect. The aircraft was flying over the Donetsk Oblast in Ukraine when it was shot down. A region that was already at the time the arena of a military conflict between separatists and the Ukrainian State. How can the Russian Federation be held responsible for the incident, even though the area is officially under Ukrainian sovereignty?

The link that must be established in order to attribute the actions to the Russian Federation, is the exercise of jurisdiction within the meaning of Art. 1 ECHR. The way in which jurisdiction is exercised can take various forms. The ECHR regime does not differentiate as to whether or not the exercise of jurisdiction was lawful according to the general rules of international law – solely the exercise of jurisdiction is decisive. Now, if the Court comes to the conclusion that the area from where the BUK-missile was shot, was under temporary or permanent jurisdiction of Russia or of Russian supported separatists, the necessary jurisdictional link would be established.

The facts in this case are somewhat reminiscent of a ‘reverse’ Bankovic situation – which Marko Milankovic has already written about. I think that the necessary link can be established if the facts indeed support this. My guess would be that the area was possibly either under Russian control or that some other kind of responsibility under the law of state responsibility concerning the handling of the weapon might be relevant. Where did the BUK-missile come from? Even if there was no direct control over the weapon, then it is a fair assumption to say that when one possesses such a weapon, one has to be careful in whose hands it ends up. If one handles it negligently and the weapon then somehow is used by private actors for shooting down a civilian aircraft, then there is a certain degree of responsibility.

I don’t want to make a final prediction on how the jurisdiction will be established, but in my opinion, it is fair to assume that Russia was exercising effective control. All of this will of course depend on the fact-finding by the Court.

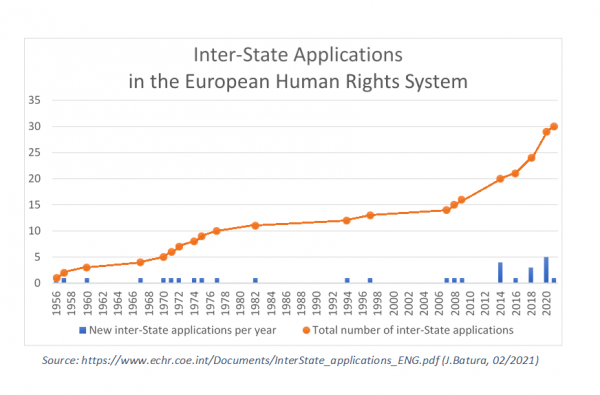

This decade saw by far the highest number of new state-to-state complaints compared to any other decade in the history of the Convention. In the last ten years alone more than in the previous 35 years. How do you explain this sudden interest in inter-state complaints?

I may have different aspects of an explanation. I think one very important aspect is the relative ease of access to the Court. Especially in comparison with the ICJ, it is fairly easy to lodge an application at the ECtHR, because there are very few requirements to make an inter-state case admissible. You can see this very clearly in the Russian cases with Georgia. While Georgia tried it both in the ICJ and the ECtHR, it failed in the ICJ. According to the ICJ, which ruled based on the compromissory clause of the CERD-Convention under Art. 22 CERD that it had no jurisdiction because of the absence of previous negotiations with Russia, these were a necessary precondition for the jurisdiction of the Court under Art. 22 CERD. Under the ECHR, there is neither a need for a dispute nor previous negotiations, the allegation of a human rights violation is enough to unlock the Strasbourg forum.

Another aspect comes to mind when you see how many cases are filed against Russia, currently 8 out of 10 cases. In fact, Russia was quite aggressive since 2007 with Georgia. This creates of course resistance and States try to use many fora, especially Ukraine which also used ITLOS and the ICJ. The ensuing question is how the Court should then deal with multi-forum litigation.

Another explanation for the growing number of inter-state cases could be that there are now 47 State Parties to the ECHR. In the earlier years of the Convention, there were in comparison very few States and they just came out of a war. Therefore, their relations were not marked by violence. Now, however, we have violence between State Parties, which makes a very big difference in the readiness to lodge an inter-state application.

Additionally, with the reform process of the inter-state procedure, more States are maybe aware of this possibility. The more it is discussed, the more it is used.

Most inter-state complaints are filed with a particular link of the applicant State to the victims. The only historical exceptions are the ‘Greek Cases’ (1967) and the ‘Turkish Case’ (1982) against military governments. However, with Gambia it is a not-affected State which referred the case concerning the alleged genocide of the Rohingya people (2019) to the ICJ. Just recently, the Netherlands and Canada announced that they will join the proceedings, the Maldives had stated a similar intention earlier this year. Similarly, the request of revision (2014) of the Ireland v. UK judgment is perceived as following ‘altruistic’ objectives. Finally, the Dutch government has made it quite clear that it ‘stands by all the 298 MH17 victims’, not only its own nationals. Isabella, in view of these applications of the last few years, would you say that we are witnessing a ‘rediscovery’ of so-called ‘altruistic cases’?

The term ‘rediscovery’ would imply that there has been a kind of ‘golden age of altruistic human rights litigation’ before, which is not really the case. However, with the Rohingya case, it is remarkable that now some States have announced that they will join the proceedings. I would also like to draw attention to the Netherlands case: there are at least two other States bound by the Convention, the UK and Germany, which had victims in the incident of MH17 and have obviously not used this possibility. It is unclear if they will join the inter-state proceedings. They can do so within 12 weeks.

Concerning altruistic cases, I would like to underline that all inter-state cases, regardless whether they were litigated for altruistic reasons or for other reasons, lead to improvements of the human rights situation on the ground. In fact, it is nice to see so-called altruistic litigation, but it is already good to have litigation in itself. Because it entails that a Court looks at the situation, conducts fact-finding and formalizes its results in a public record. Such a judgment, which documents the suffering inflicted on individuals, can and should, immediately and also in historical perspective, serve as a source of embarrassment for the State concerned. But perhaps we already live in an age of post-shame.

In sum, I am not sure if we live a period where we see more of this altruism, but I welcome the more frequent use of the inter-state application by States.

Isabella, you have been invited to advise the Steering Committee for Human Rights (Comité directeur pour les droits de l’Homme, CDDH), which is responsible for intergovernmental work of the Council of Europe in the human rights field. Due to the mentioned growing number of pending inter-state cases, the CDDH has been asked to make proposals to improve the inter-state procedure. Could you please explain briefly where the main problems of the current procedure lie?

The point of departure for this reform process is that we have a very busy Court with thousands and thousands of pending applications. Almost 20% of these applications relate to inter-state conflicts. This creates a certain pressure on the Court, which leads to various problems.

One of these problems is that many of these applications, both individual cases referring to inter-state conflicts and the inter-state applications as such, require fact-finding. Since there are often no domestic remedies because the State has collapsed in a certain way or because the remedies are ineffective, the Court is put in the position of a first instance Court. It has to establish which State exercised jurisdiction and what happened. This is no easy task for a Court that must deal with so many thousands of applications. This explains also why this kind of application takes a relative long time.

Within this reform process of the inter-state procedure, what options are available, and which do you consider most effective?

In fact, the States’ room for manoeuvre for reform is rather limited.

One option would be a protocol that would somehow outsource the fact-finding, for example by creating a fact-finding body similar to the old Commission. But in view of the current political situation, a protocol is rather unlikely. Russia is trying on all levels to reduce the possible room for manoeuvre further, as it for example excluded reform considerations in the context of the execution of inter-state judgments.

Another option could be a change of the rules of the Court, which is the prerogative of the Court.

Concerning the substantive aspects of the reform, I have been asked as an expert to research and elaborate on three elements in particular.

The first aspect concerns friendly settlements. This tool could help to ease the workload of the Court. The question is then, what the Court can do to facilitate possible friendly settlements between the State Parties and at the same time preserve its judicial impartiality. This necessarily includes the question whether friendly settlements are a good thing or a bad thing, which is a very principled question. In my opinion, settlements are not necessarily a bad thing, given the lack of enforcement of the existing judgments in inter-state cases against Turkey and Russia. Maybe friendly settlements could lead to some tangible results. With Russia, I think it is generally very difficult.

In general, direct settlement negotiations do not take place. I would suggest employing the senior staff of the Registry more actively. This approach could help to get at least certain things off the table and thus reduce the workload of the Court. The old Commission had more room and a more explicit mandate to seek friendly settlements.

Another question that I was asked to elaborate on relates to the possible supervisory deterrent effects of interim measures in inter-state proceedings. This might be an avenue to contain the worst human rights violations by drawing attention to a given theatre of acute conflict, similar to a huge spotlight. By using interim measures, the Court could request information about certain ongoing situations and try to raise awareness of basic obligations under international law of the actors involved.

The last issue which is relevant for the reform process is the relationship between inter-state proceedings and overlapping individual procedures. The Convention does not regulate this question because the drafters did not foresee that both procedures would be available simultaneously. In the beginning of the history of the Convention, the individual application was just optional, and the inter-state application was the default mechanism. Therefore, their relationship today remains unclear. One possible solution would be to put all individual cases that relate to a certain, common problem on hold and to use the inter-state proceeding as a kind of a ‘pilot procedure’. If, for example, there were a judgment establishing the responsibility of a State under Art. 1 ECHR, this finding could then be used also in the pertinent individual cases and would reduce the workload for the Court. This approach guides the Court for example in the cases about Eastern Ukraine.

Maybe we can also use this interview to raise awareness of the risk of a counterproductive formulation, which I found in one of the documents and which really worries me.

There has been a recommendation to ask applicant States ‘to submit from the outset a list of clearly identifiable individuals who are victims of the alleged human rights violations’ (para. 6 and 45). Indeed, this would make it very, very hard for applicant States to submit an application, because it would mean that they would first have to somehow identify individual victims in another State. In fact, the biggest advantage of the inter-state procedure is precisely that it does not require an individual victim and instead allows applications against abstract legislation or against so-called administrative practices that contravene the convention.

Therefore, I hope this idea does not come to fruition. Of course, these documents are not legal sources in a formal sense. But if States that are considering an application for altruistic reasons, for example in cases like Turkey, would feel required to submit a list of victims at the beginning of the procedure, then it becomes very remote that States would even consider such an application. While I understand that it is important for the stage of just satisfaction to have a clear idea of the identity of victims, this broad formulation is in my view counterproductive.

I hope that the direction of this whole reform process is not to render inter-state complaints more difficult, but to actually encourage States to make more use of it.

Isabella Risini is currently a lecturer for public law at the law faculty of Ruhr-Universität Bochum and managing director of the Center for International Affairs. She is a member of the scientific advisory board of Völkerrechtsblog. In the summer term 2023, she will be a visiting professor at the Walther Schücking Institute for International Law at the Christian-Albrechts-University in Kiel. In the winter term 2021/22, she was a visiting professor of Public Law at Augsburg University.

Justine Batura is a Berlin-based lawyer in the field of energy law, with a focus on renewables and the related national, European and international authorisation and subsidy law. With an LL.M in international law and practical experiences in international bodies, she has a solid background in international law. Her areas of interest include International Human Rights Law, Sustainability Law, Comparative Constitutional Law, and Fundamental Rights.

Ass. iur. Lukas Kleinert, Master Droit, LL.M. is writing his Ph.D. at the University of Hamburg on an European and public international law related topic. He has been a member of the editorial team of the Völkerrechtsblog since 2018.