Where Law Ends, Harm Begins

The Human Rights Failure of Germany’s Pushback Regime

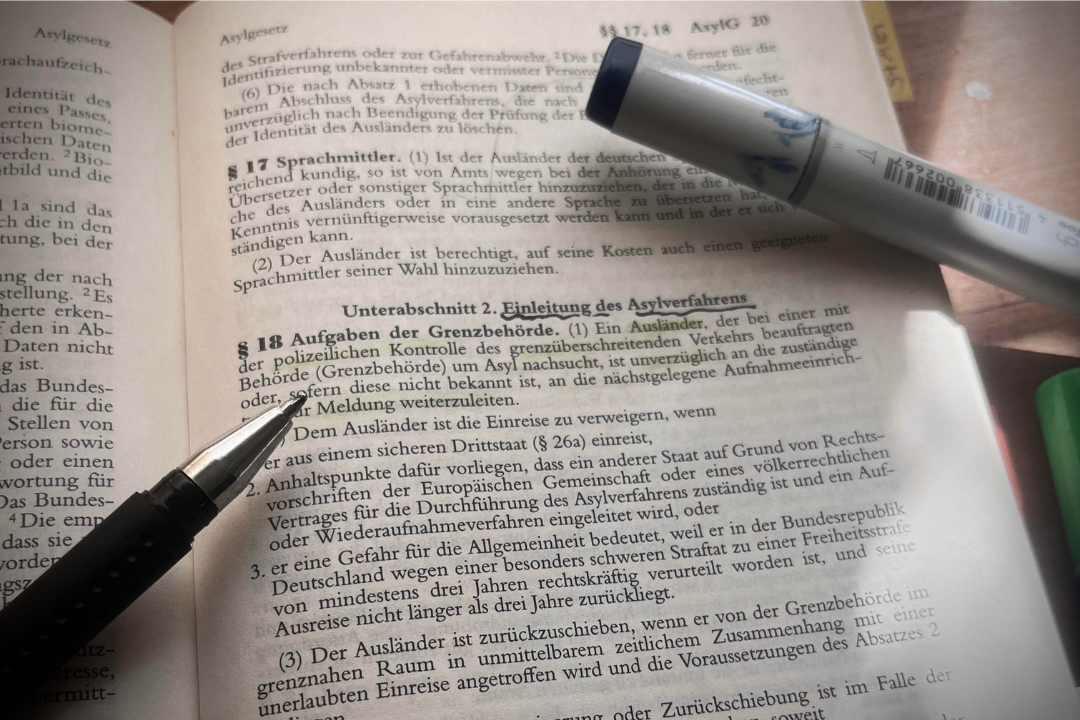

In early May 2025, the recently elected German government implemented a highly controversial border policy aimed at intensifying checks along its borders with Poland and the Czech Republic. Initiated by Interior Minister Dobrindt (CSU), it targets asylum seekers entering Germany through EU Member States deemed safe. Under his decree from May 7, German federal police systematically denied entry by invoking §18 Asylgesetz (AsylG) and referencing public order exceptions under Article 72 TFEU. The only exemptions applied to vulnerable individuals such as children, pregnant women, and severely ill migrants. The government’s justification centred on claims of ‘uncontrolled secondary migration’ and alleged dysfunction within the European asylum framework, specifically the Dublin III Regulation. Additionally, Dobrindt argued that the measures were necessary to counter hybrid warfare tactics used by Russia and Belarus, accused of weaponizing migration against the EU.

Subsequently, three Somali nationals, having transited through Poland from Belarus, attempted entry at the Frankfurt (Oder) train station on May 9, 2025. After immediate denial of entry and forced return to Poland, they sought judicial intervention to secure their right to initiate asylum procedures in Germany. These legal challenges underline significant tensions between German national measures and obligations arising from EU law and international human rights law, particularly regarding safeguards against potential chain refoulement — that is, the risk of being returned to the country of origin via multiple states without a proper asylum procedure in any of them. This post critically examines the legality of Germany’s new border policy through the lens of not only EU law, but also European human rights law, specifically Articles 3 and 4 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU (CFR) and Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

II. A Judicial Reversal: Ruling from the Berlin Administrative Court

On June 2, the Berlin Administrative Court delivered a landmark interim decision sharply condemning Germany’s pushback policy. The court ordered German authorities to permit the Somali plaintiffs entry into Germany and initiate the procedure to assess whether Germany or another EU Member State is responsible for examining their asylum claims – under Dublin III procedures (pp. 9-12). Crucially, the Court concluded that the asylum requests made within German territory activated Germany’s obligations under Dublin III. Consequently, the Court explicitly rejected the applicability of §18(2) AsylG, emphasising that EU law overrides conflicting national provisions (pp. 11-14).

Furthermore, the Court emphasised the unlawful nature of systematic border refusals based on the assumption of Poland as a ‘safe third country’ without individually assessing each case in a full Dublin III procedure, including a mandatory personal interview and comprehensive procedural safeguards (pp. 14-15).

A central component of the ruling concerned the government’s reliance on the public order exception under Article 72 TFEU. The court rejected Germany’s arguments, finding insufficient evidence of an ‘actual, present, and sufficiently serious threat’ justifying derogation from EU law (pp. 16-19). This section highlights significant shortcomings in the German government’s rationale and stresses the strict interpretative limits placed on Article 72 TFEU by established EU jurisprudence.

Despite this clear judicial rebuke, Minister Dobrindt maintained a defiant stance, asserting that intensified border controls would continue and announced intentions to seek definitive clarification from the European Court of Justice (CJEU). Chancellor Merz endorsed this combative approach, aligning with the CDU/CSU’s broader political strategy aimed at demonstrating a hardline stance on migration.

Although formally limited to the Somali plaintiffs, the ruling establishes an influential ‘precedent’ with potentially far-reaching consequences for Germany’s asylum practices, explicitly challenging the applicability of §18 AsylG to bypass European obligations.

III. Assessing the Lawfulness of Pushbacks under the EU Charter and the ECHR Human Rights Frameworks

Pushbacks at the border without an individual assessment – merely on the basis that the migrant transited through or arrived from a third safe country – are likely to pose a threat to asylum seekers (chain refoulement), making such practices highly problematic. Thus, MoP Mihalic called the decision ‘a heavy defeat for the federal government’ and a warning not to stretch the law for populist purposes. EU-law expert Bornemann echoed this, stating that ‘pushbacks of asylum-seekers simply aren’t permissible.’ These responses highlight what is at stake: whether such practices comply with EU and human rights law.

Presumption of Safety, Mutual Trust, and the Limits of the Dublin III Regulation

The Dublin system is built on the bona fide presumption that all participating countries, respecting the principle of non-refoulement, are considered safe for third-country nationals. Accordingly, transfers of asylum applicants under the ‘take back’ or ‘take charge’ procedures are presumed to comply with the Refugee Convention.

However, this cannot exempt States from verifying – even at the border – whether the rejection of a migrant could expose them to the risk of treatment prohibited under Article 4 CFR. Article 3(2) Dublin III Regulation prohibits transfers to MS where systemic flaws in asylum procedures or reception conditions could result in ill-treatment as defined in Article 4 CFR. Although in CK (§§ 97) the ECJ initially loosened the requirement of systemic deficiencies in favour of a more individualised assessment, more recently in CZA (§142) and X (§61) the Court adopted a restrictive interpretation, reaffirming that transferring States may assess a real risk under Article 4 CFR where systemic deficiencies exist in the asylum system of the receiving State.

Nonetheless, this does not exempt national authorities from examining ex officio whether publicly available information indicates that the asylum seeker would face a real risk of violation of Article 4 CFR after transfer, due to systemic deficiencies in the responsible MS’s asylum or reception system.

Moreover, even if the Dublin III Regulation were bypassed relying on Article 72 TFEU, Germany would still remain bound by its obligations under the ECHR.

The ECHR’s Perspective: Procedural Obligations under Article 3 ECHR

It is well-established (Soering §§ 90-9; Hirsi Jamaa, § 114) that any measure to remove an alien potentially raises issues under Article 3 ECHR and engages the responsibility of the State where substantial grounds have been shown for believing that the person would face a real risk of treatment contrary to Article 3 in the receiving country.

In cases where a State seeks to remove asylum seekers to a third country, the ECtHR has clarified that the State’s responsibility remains intact: if there are substantial grounds to believe that removal would expose the individual – either directly (in the third State) or indirectly (e.g., via chain-refoulement) – to treatment in violation of Article 3, the State remains accountable. Where a State seeks to remove an asylum seeker to a third country without examining the asylum claim on its merits – as in the present case -, it has a procedural duty to examine the conditions in the country concerned, particularly whether the individual will have access to an adequate asylum procedure. This is because the removing State operates under the assumption that the asylum claim will be examined on the merits by the competent authorities of the receiving third State, if such a request for removal under Dublin III is made.

The ECtHR has consistently held (see M.A. v. Cyprus, §94; Ilias and Ahmed v. Hungary, §§124–141) that where a State seeks to remove an asylum seeker to a third intermediary country without examining the merits of their claim, it must carry out a thorough risk assessment. Specifically, the State must determine whether there is a real risk that access to an adequate asylum procedure will be denied—one that offers effective protection against refoulement. If guarantees are insufficient, Article 3 implies a duty not to remove the individual. In the present case, this duty is particularly relevant: both Poland and Lithuania have been criticised for systematic pushbacks, and multiple NGO and independent reports indicate a concrete risk of chain refoulement, potentially reaching Belarus.

IV. Conclusion

It is worth noting that by insisting on ‘systemic deficiencies’ as the threshold for assessing human rights risks in Dublin cases, the ECJ appears to have departed from its earlier approach and set itself on a potential collision course with the ECtHR.

However, under Article 52(3) CFR, the meaning and scope of the rights guaranteed therein must be interpreted not only in light of the text of the ECHR but also of the ECtHR’s case law – as the Court itself has recognized (Jaramillo §49). This makes the Luxembourg Court’s recent approach all the more puzzling.

Moreover, the EU legislator, in the new Asylum and Migration Management Regulation repealing Dublin III, has clearly chosen a different path. Notably, the term ‘systemic flaws’ no longer appears. Under the revised provision on human rights exceptions to transfers, it is sufficient that there is a real risk of violating Article 4 CFR to preclude a transfer. This legislative development has clear implications for the case at hand: willingly or not, the ECJ will have to align with the direction taken by the EU legislator – so will the MSs. Germany’s current approach, however, shifts towards the opposite direction – bypassing individualised assessments and undermining these binding obligations.

Far from addressing legal gaps in the EU system, the German ministerial decree openly disregards the safeguards enshrined in both EU and human rights law. If Germany continues down this path, it risks not only undermining mutual trust within the EU but also continuingly violating its obligations under binding international norms.

Ruggero Leotta is a research assistant at the University of Groningen. He previously worked at the Italian Ministry of Justice, serving at the Migration and Asylum Court. His research focuses on European and international human rights law, with a particular emphasis on the principle of non-refoulement.

Hendrik Mathis Drößler previously worked at the T.M.C. Asser Institute, as well as in the German Bundestag and the Lower Saxony State Parliament. He holds an LL.M. in Public International Law (cum laude) from the University of Groningen and a double Bachelor’s degree in Law and Political Science from the University of Göttingen. His research explores rule of law issues, with a focus on compliance with the International Court of Justice and international humanitarian law.