In recent years, Colombia and Peru have clashed over the sovereignty of Isla Santa Rosa, a landmass formed in the 1960s by Amazon River sedimentation. Over time, accretion joined it to Isla Chinería, a Peruvian island near the triple frontier with Brazil. Soon after, Peruvian settlers established a town there. Colombia, however, argues that Isla Santa Rosa was never assigned to either country under the 1922 Lozano-Salomón Treaty and therefore Peru is wrongfully occupying the island.

This dispute is more than a bilateral quarrel. It raises broader questions about how international law responds to shifting river boundaries, the impact of environmental change on territorial sovereignty, and the resilience of treaties drafted a century ago in the face of dynamic natural processes. It also highlights the fragility of Colombian–Peruvian relations and the potential role of third states such as Brazil.

To explore these dimensions, the essay first sets out the historical and legal framework of the border, analyzing the 1922 Lozano-Salomón Treaty and subsequent demarcation. It then examines the jurisdictional options available, followed by an assessment of the parties’ arguments. Ultimately, the essay reflects on the need for flexible legal frameworks, cooperative sovereignty, and creative dispute-resolution mechanisms when environmental forces reshape borders.

Background: Rising Tensions

Tensions began in 2024 during a joint commission meeting where the Mayor of Santa Rosa de Yavarí (Peruvian city) emphasized the need for cooperation, whilst the Colombian Director of Sovereignty countered that the island, ‘Colombian land’, was being irregularly occupied by Perú. Outraged, the Peruvian mayor left, and the Peruvian Ministry of Foreign Affairs raised a note verbale of protest, which was answered superficially by Colombia. In August 2025, President Petro reignited the controversy by stating on X that Peru violated the Rio Protocol by creating a special district on the island on Colombian land.

It is worth mentioning that diplomatic relations between the two countries have eroded in the last years. Relations worsened after Petro supported former Peruvian President Castillo, and since them, official communications have been done via the Chargé d’Affaires.

1922 Lozano-Salomón Treaty

The Colombo-Peruvian border was defined in 1922 by the Lozano-Salomón Treaty. Article 1 states that:

“The boundary line between the Republic of Colombia and the Peruvian Republic is hereby agreed upon, agreed and fixed in the terms hereinafter expressed: (…) from there along the thalweg of the Putumayo River to the confluence of the Yaguas River; follows by a straight line that from this confluence goes to that of the Atacuri River in the Amazon, and from there by the thalweg of the Amazon River to the limit between Peru and Brazil established in the Peru-Brazil Treaty of October 23, 1851.

The high contracting parties declare that all and each one of the differences that, because of the limits between Colombia and Peru, had arisen up to now, are definitively and irrevocably terminated, and that henceforth none may arise that alters in any way the border line established in the treaty.”

From the text, it is clearly stated that for the Amazon segment of the boundary, the limit is in the Thalweg. Although originally a geographical term, the Thalweg is recognized under international law—e.g. Kasikili/Sedudu Island (Botswana/Namibia) and Benin v. Niger—as the ‘main channel,’ meaning the middle of the primary navigable channel of a waterway. In most cases, it coincides with the deepest point of the channel, but it should not be confused with the exact midpoint between the riverbanks.

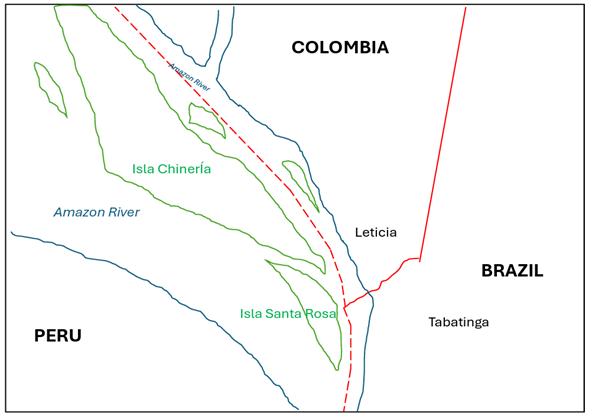

Although the limits were defined, it was not until 1929 that the demarcation commission established the milestones. Island’s regime was decided by the commission in the following terms:

“(…)these are affected as follows: they belong to Colombia: Zancudo II island, Loreto islands, Santa Sofía Islands, Arara Islands, Ronda Island and Leticia Island; and they belong to Peru: Tiger Island, Coto Islands, Zancudo I island, Cacao Island, Serra Island, Yahuma Island, and Chinería Island.”

The commission considered the distribution of islands depending on the nearest shore (see. Act 2). This demarcation did not, in every case, correspond with the Thalweg.

Figure 1: Island Distribution according to the 1929 Commission. (Google Maps).

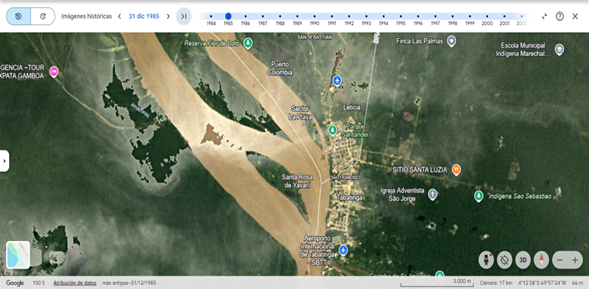

Figure 2: Santa Rosa Island. Author´s own creation.

Figure 3: Santa Rosa Island in 1985, Satellite View. Google Earth.

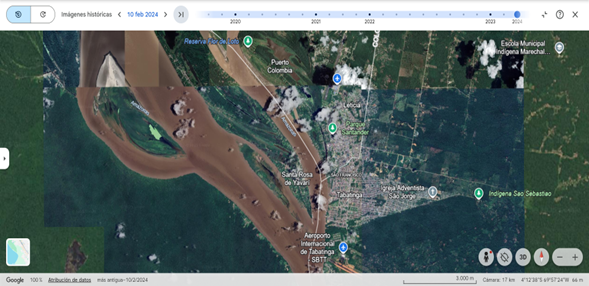

Figure 4: Santa Rosa Island in 2024, Satellite View. Google Earth.

Jurisdictional Clause

As a result of the 1929 distribution, Peru invaded Leticia in 1932. The war ended with the Rio Protocol, which confirmed the status quo ante bellum. The Protocol reaffirmed the 1922 Treaty and established in Article VII a jurisdictional clause for the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ) to resolve any conflict between the parties.

In 1948, the Bogota Pact granted the ICJ jurisdiction over regional disputes, but Colombia later withdrew after losing cases to Nicaragua to avoid future territorial litigation. However, the Rio Protocol does have a jurisdictional clause. Protocol’s reference to the PCIJ applies to the ICJ via Article 37 of the statute. Considering the weakened relations between Colombia and Peru, it would not be outrageous to consider submitting the matter to the ICJ. Colombia proposed reactivating the joint commission and hinted at international options, as Armando Benedetti, Minister of the Interior, mentioned that resorting to The Hague is not ruled out.

Understanding Colombian Arguments

Colombia argues that the key issue lies in the distinction between delimitation and demarcation, emphasizing that the border follows the thalweg. Since the thalweg can shift due to natural changes in the river, landmasses like islands may change sides over time. While maps show the border following the eastern branch north of the islands, current river conditions suggest the main thalweg may now lie south of Santa Rosa Island.

During the Kasikilo/Sebundi Island case, the ICJ concluded that the present-day state of scientific knowledge could be used to illuminate the terms of the treaty. Elements include, i) the most suitable channel for navigation on the river, ii) the line determined by the deepest soundings, or iii) the median line of the main channel followed by boatmen travelling downstream. Moreover, according to the Draft concerning the international regulation of fluvial navigation of 1887, “the boundary of states separated by a river is indicated by the thalweg, that is to say, the median line of the channel”. From a technical aspect, geographic methods for determining the Thalweg include photointerpretation, field measurement, and transfer and digitalization. The deepest and/or middle of the navigation channel depends on the interaction between flow rate, energy, and morphology. Processes such as sedimentation and avulsion change their velocity and trajectory. Therefore, the middle of the main channel does not correspond with the geographical center halfway between the banks.

Current studies show that the westernmost branch of the river has the deepest draught and is the most navigable. The middle channel between Chinería and Ronda is completely closed and fully sedimented. The same happens between Chinería and Santa Rosa. Even considering the different definitions of the Thalweg, the sediment and depth of the Western branch makes it the best navigable option. In this order of ideas, if the Thalweg goes south-west of the island, all land north-eastern of the line should be Colombian..

According to the Colombian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, all new islands are subject to demarcation. Colombia argues that the 1929 demarcation expressively states the regime regarding existing islands. As part of this regime, Santa Rosa is not even mentioned. An interpretation of the word existing suggests that the parties recognized that new formations may arise and shall be delimited based upon party agreements or a Court’s decision. It may also be the case that when the commission agreed upon the islands, there was specific attention to the use of plurals as “Loreto islands”, which comprise a series of smaller islands close to the main one. This is not the case of Chinería Island, deliberately named as a singular entity. Hence, it is not possible to consider Santa Rosa inside a group of Chinería. Additionally, considering Act No. 2, Santa Rosa’s nearest point is less than 1 km to the Colombian shore and almost 2 kilometers away from Peru.

Understanding Peruvian Arguments

Peruvian Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued an additional note verbale of protest, answering Colombian allegations. Peru argues that Isla Santa Rosa is an integral part of Isla Chinería and, therefore, included in the 1929 demarcation. Hence, as the present state of the boundary, the island is south of the 1922 Thalweg line.

Moreover, Peru, which has the status quo in its favour, has displayed continuous and peaceful acts of sovereignty since 1974, when Santa Rosa de Yaravi was founded. The population of the town identifies as Peruvian, and administrative authorities respond to the governor of Loreto. Although the titre de souverain may not be cleared (as Santa Rosa Island was not included in the 1922 Treaty, nor by the demarcation commission), as explained in the Islands of Palmas case, “an inchoate title could not prevail over the continuous and peaceful display of authority by another State.”

Albeit disputed, as explained by the Peruvian Society of International Law, natural phenomena such as avulsion may not reshape the boundary and shall maintain the original shape as explained in the Helmand River case (1872). Furthermore, the prohibition of the rebus sic stantibus over boundaries under Article 62(2)(a) of the VCLT applies to the case.

Brazil as a Third Party

Finally, the potential role of a third country like Brazil should not be underestimated. Not only is Santa Rosa Island located just meters from the triple border, but Brazil has historically been a key player in Colombian-Peruvian relations over the border. A renegotiation of the agreement on the Thalweg could affect Brazil, as Tabatinga´s access to the Amazon may also be restricted. Hence, it would be interesting to analyze the possibility of its participation in a hypothetical process before the ICJ. However, this would present an obstacle because the Rio protocol does not include Brazil, so there would be no instrument vis-à-vis Colombia that would make its participation in the dispute possible.

Alternatives and Prospect

In the future, even if this dispute is submitted to International Tribunals, Santa Rosa will most probably continue to be under Peruvian sovereignty, mainly due to the continuous and peaceful display of sovereignty. Nevertheless, other options include treaty adjustment or shared sovereignty, considering the mutable nature of a border demarcated by the Thalweg (see. Meuse River border readjustment treaty between Belgium and the Netherlands), or the creation of a condominium such as the one in Pheasant Island between France and Spain.

Another consideration, albeit somewhat far-fetched and hypothetical, is that this is a media spectacle designed to explore a hidden interest: the joint dredging of the Amazon. All in all, the main concern of Colombia, besides sovereign issues, is that future sedimentation of the river will leave Leticia without direct access to the river. Such dredging would be beneficial to all three states, although covering the costs is a complex matter. The diplomatic crisis may present the perfect excuse to address the issue.

Beyond dredging, river drought and shifting waterways raise concerns far beyond Colombia and Peru. As climate change intensifies, reduced flows and sedimentation threaten to alter river courses worldwide, challenging borders long defined by fluvial boundaries. This issue has implications for every state whose frontier relies on a river, yet international case law on shifting boundaries remains scarce. The few cases—such as Kasikili/Sedudu Island (Botswana/Namibia) and Benin v. Niger—show how different methodologies can produce different outcomes in applying the Thalweg principle and determining a critical date, underscoring inconsistent jurisprudence. The Santa Rosa dispute thus highlights both a bilateral conflict and a broader gap in international law that will grow more pressing in years ahead.

Despite strained relations, a deeper understanding of the arguments of Colombia and Peru could lead to peaceful solutions. Ultimately, the dispute underscores the need for clearer regulations on Amazon islands and illustrates how states must adapt international law to the realities of shifting river boundaries.

Gabriel Andrés Concha Botero is a Colombian lawyer and consultant at the International Direction of the National Agency for Legal Defense of the State, and currently pursuing a Master’s in International Law at Universidad del Rosario.