A decade ago, in 2015, ITLOS delivered its first-ever advisory opinion as a full tribunal in the Request for an Advisory Opinion submitted by the Sub-Regional Fisheries Commission (SRFC). By asserting advisory jurisdiction under Article 21 of its Statute, the Tribunal sparked controversy, with many scholars and states arguing that UNCLOS never intended to confer such jurisdiction. Since then, ITLOS has issued another advisory opinion, in 2024, in the Request for an Advisory Opinion submitted by the Commission of Small Island States on Climate Change and International Law. This time, criticism was muted: only China and Brazil objected, while countries that had previously opposed it, such as the UK and France, acknowledged the Tribunal’s jurisdiction, with France noting in its submissions that “…the Tribunal’s advisory jurisdiction now seems to be accepted” (para. 9).

A decade later, in light of recent developments, including Brazil and China’s June pledges at the Third UN Ocean Conference to ratify the BBNJ Agreement, which explicitly grants ITLOS full advisory jurisdiction and is set to enter into force in January 2026, it is timely to revisit the Tribunal’s advisory competence. France’s statement signals a pivotal moment, suggesting that ITLOS’s advisory jurisdiction has been consolidated through subsequent practice under Article 31(3)(b) of VCLT. This post is structured as follows: First, an overview of UNCLOS provisions on advisory jurisdiction; second, a discussion of the debate surrounding ITLOS’s 2015 advisory opinion; third, an assessment of the Tribunal’s advisory jurisdiction a decade later in light of objections by China and Brazil; and fourth, an examination of how the silence of many States bears on that jurisdiction.

The Silence of UNCLOS on Advisory Jurisdiction

As ITLOS itself acknowledged in 2015, “[n]either the Convention nor the Statute makes explicit reference to the advisory jurisdiction of the Tribunal” (Advisory Opinion of 2 April 2015, para. 53). Here, advisory jurisdiction refers to that of the full Tribunal, not the Seabed Disputes Chamber’s limited Article 191 jurisdiction, which is confined to matters of the Area. The main jurisdictional provision of UNCLOS, Article 288(1)-(2), refers only to “disputes,” which suggests that the courts and tribunals established under Article 287 were intended to exercise jurisdiction solely in contentious proceedings:

“A court or tribunal referred to in article 287 shall also have jurisdiction over any dispute concerning the interpretation or application of an international agreement related to the purposes of this Convention, which is submitted to it in accordance with the agreement.” (emphasis added)

Article 21 of the ITLOS Statute (Annex VI to UNCLOS) goes a step further. It provides jurisdiction over: a) “disputes,” which clearly covers contentious cases; b) “applications,” which concern requests for prompt release of vessels and crews or for provisional measures (Advisory Opinion of 2 April 2015, para. 55); and c) “matters,” the term that lies at the heart of the debate on ITLOS’s advisory jurisdiction:

“The jurisdiction of the Tribunal comprises all disputes and all applications submitted to it in accordance with this Convention and all matters specifically provided for in any other agreement which confers jurisdiction on the Tribunal.” (emphasis added)

Unlike these provisions, Article 138 of Rules of the Tribunal, adopted in 1997 under Article 16 of UNCLOS and amended twice since, expressly provides for advisory jurisdiction:

“The Tribunal may give an advisory opinion on a legal question if an international agreement related to the purposes of the Convention specifically provides for the submission to the Tribunal of a request for such an opinion.”

Yet, because procedural rules cannot expand the Tribunal’s jurisdiction beyond what UNCLOS and its Annexes permit, the legal basis for ITLOS’s advisory jurisdiction could ultimately rest only on Article 288 of the Convention and Article 21 of the Statute.

The Controversy over ITLOS’s Advisory Jurisdiction

The Tribunal held that although Article 288 of UNCLOS refers only to “disputes,” ITLOS nonetheless possesses advisory jurisdiction on the basis of Article 21 of its Statute, since “…the Statute enjoys the same status as the Convention” (Advisory Opinion of 2 April 2015, para. 52). The Tribunal held that “matters” in Article 21 must extend beyond “disputes,” otherwise the text would have used the same term (para. 56). It therefore interpreted “matters” to include advisory jurisdiction when expressly conferred by “any other agreement” under Article 21 (paras. 56–58). Regarding Article 138 of the Rules, the Tribunal clarified that it does not itself create advisory jurisdiction but merely “furnishes the prerequisites” for its exercise (para. 59).

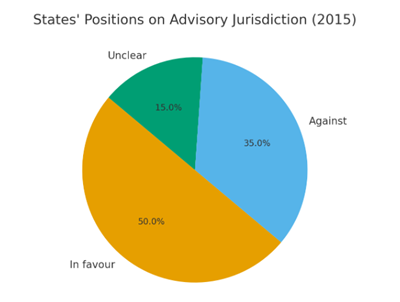

Scholars and states raised two principal objections to the Tribunal’s reasoning. First, Article 21 of the ITLOS Statute merely mirrors Article 36(1) of the ICJ Statute, which was never intended as a legal basis for advisory jurisdiction but only for contentious jurisdiction (cf. Virginia Commentary, vol. V, p. 378; Lando, p. 451; Written Statement of Portugal, para. 10). Second, Articles 21 of the ITLOS Statute and 288 of UNCLOS must be read consistently (Written Statement of the UK, para. 22; Tanaka, 327). Since Article 288 cannot reasonably be construed as conferring advisory jurisdiction, it is implausible that Article 21 was intended to establish a broader jurisdictional basis than that provided by Article 288. Perhaps a “subsequent practice” argument interpreting Article 21 was unavailable to the Tribunal in 2015. Of 22 written statements, only 10 supported (implicitly or explicitly) its advisory jurisdiction, 7 opposed and 3 were unclear. With only half in favor, there was plainly no agreement, making it impossible to invoke “subsequent practice” to assert jurisdiction.

The Current Standing of ITLOS’s Advisory Jurisdiction: Making Sense of Objections

Article 31(3)(b) of the VCLT provides that treaty interpretation must consider, alongside the ordinary meaning and the object and purpose, “any subsequent practice in the application of the treaty which establishes the agreement of the parties regarding its interpretation.” Subsequent practice is an authentic means of treaty interpretation and carries equal weight to the other means under Article 31 (Commentary to Draft Conclusion 3, pp. 23-27). The number of states actively engaging in the practice may vary and silence by one or more parties can amount to acceptance, where “the circumstances would reasonably call for some action” (Draft Conclusions 5, 10). Scholars generally agreed after 2015 that the interpretative tools available left the meaning of Article 21 of the ITLOS Statute ambiguous (Lando, p. 450; Tanaka, p. 326). The question, then, is whether subsequent practice can now help clarify that meaning in light of more recent developments.

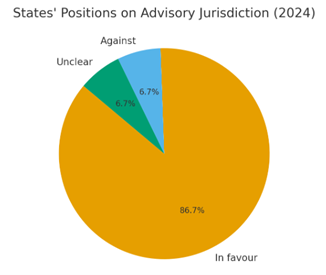

In 2024, during the climate change advisory opinion, 26 out of the 31 states that submitted written observations either explicitly or implicitly accepted the Tribunal’s jurisdiction, including states that had previously opposed it, such as France and the UK. Only two states, China and Brazil, maintained their objections, while two others, Japan and Australia, adopted a more cautious approach, framing their remarks on the Tribunal’s advisory jurisdiction as questions for the Tribunal to clarify (Written Statement of Japan, pp. 1-2; Written Statement of Australia, paras. 4, 16). In short, roughly 87% of participating states endorsed ITLOS’s advisory jurisdiction, with only China and Brazil in opposition. The evolution of state practice over the span of nine years is striking: by 2024, the Tribunal’s jurisdiction was being increasingly accepted as “subsequent practice.”

However, “agreement” on the interpretation under Article 31(3)(b) of the VCLT must be established among all parties, unlike Article 32, which applies to subsequent practice reflecting only some parties’ views (Commentary to Draft Conclusion 2, p. 20). Thus, unless China and Brazil have also accepted the practice, no “agreement” under Article 31(3)(b) exists. That said, after China and Brazil submitted their written statements in June 2023, a notable development occurred: in September 2023, both states signed the BBNJ Agreement, whose Article 46(7) provides:

“The Conference of the Parties may decide to request the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea to give an advisory opinion on a legal question on the conformity with this Agreement of a proposal before the Conference of the Parties on any matter within its competence.” (emphasis added)

The provision essentially mirrors the three requirements in Article 138 of the Rules: a duly authorized “body” may request an advisory opinion on a “legal question,” depending on the “other agreement.” By signing the BBNJ Agreement, China and Brazil have, in principle, accepted the Tribunal’s approach to “matters” under Article 21. At the Third UN Ocean Conference in Nice (June 2025), both states further pledged to ratify the Agreement, reinforcing their practical endorsement of ITLOS’s advisory jurisdiction (see here and here).

The Current Standing of ITLOS’s Advisory Jurisdiction: Silence as Acceptance

The next question concerns how to interpret the silence of states that neither objected to nor endorsed the Tribunal’s advisory jurisdiction. The ILC notes that the phrase “all parties” was deliberately omitted from Article 31(3)(b) VCLT to avoid requiring every party to participate in subsequent practice. (Yearbook of the ILC, p. 222; Draft Conclusions 5, 10). Still, treating silence as agreement sets a high bar and depends on context: the state must be aware of the practice, have every opportunity to react, and fail to do so (Military and Paramilitary Activities, para. 38; EC-Computer Equipment, para. 272; Draft conclusions with commentary, p. 79). The ICJ likewise applies a context-specific approach. In boundary disputes, it sets a stringent threshold, presuming legal title and requiring any claim of acquiescence to start from that presumption (Land and Maritime Boundary between Cameroon and Nigeria, paras. 64, 67; Draft conclusions with commentary, p. 80). By contrast, when dealing with the practice of international organizations, the Court has shown a greater willingness to infer member-state consent. Several authors have identified this pattern (Arato, 2010, p. 460; Buga, 2018, p. 67), which I refer to here as “collective acquiescence.” In this context, states may be taken to accept an organization’s consistent practice unless they object, given the public and official nature of that practice, which affords them “every opportunity of accepting or rejecting” it (Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua, para. 38).

In Nicaragua, the Court treated official publications, such as the ICJ Yearbook, as evidence of subsequent State practice, thereby concluding that Nicaragua’s acceptance of PCIJ jurisdiction remained valid under Article 36(5) and could be invoked against any State with a declaration under Article 36(2), including the US. In the Namibia Advisory Opinion, the Court relied on Security Council practice to interpret Article 27(3), holding that the resolution on Namibia was valid despite two permanent members’ abstentions, which did not negate the required “concurring votes.” In the Certain Expenses Advisory Opinion, the General Assembly’s practice, particularly its adoption of resolutions, was central to interpreting “expenses of the Organization” under Article 17(2) of the UN Charter. Throughout, the Court looked to collective practice, often foregrounding the voting outcome of the organ rather than the views of individual members.

The subsequent practice relating to ITLOS’s advisory jurisdiction exhibits similar characteristics. The advisory jurisdiction of the full Tribunal has been consistently referenced, particularly with regard to Article 138 of the Rules, in ITLOS Yearbooks since 1997 under the headings “Jurisdiction” or “Competence.” The Basic Texts volumes published in 1998, 2005, and 2015 likewise include the Rules. Furthermore, the Guide to Proceedings before the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, published and periodically updated by the Tribunal, provides guidance on the advisory jurisdiction of the full Tribunal as provided for in any international agreement.

Reports of the Meetings of States Parties indicate that the issue is seldom addressed: While some States note that the Statute lacks an express grant of advisory jurisdiction beyond the Seabed Disputes Chamber, they also accept that other agreements may confer it, effectively endorsing ITLOS’s approach. (Twenty-third Meeting, para. 21; Twenty-fifth Meeting, para. 23; Twenty-sixth Meeting, para. 25). Delegations have responded positively to the Tribunal’s advisory proceedings on climate change, and the reports record no negative views regarding its advisory jurisdiction (Thirty-fourth Meeting, para. 15; Thirty-fifth Meeting, para. 12). Likewise, the President’s consistent welcome of the conferral of advisory jurisdiction in the then-pending BBNJ Agreement met with no objections (Thirty-second Meeting, para. 17; Thirty-third Meeting, para. 19).

Additionally, ITLOS’s practice over the past decade, reflected in two advisory proceedings (2013–2015 and 2022–2024), marks a significant development under UNCLOS. Silence in response, given the institutional practice noted above, can only reasonably be read as acceptance. This is reinforced by the fact that roughly 75% of UNCLOS parties have signed the BBNJ Agreement, which presupposes ITLOS’s advisory jurisdiction and will enter into force in January 2026. Taken together, these developments make continued silence increasingly difficult to interpret as anything other than acceptance.

To translate France’s remark that the Tribunal’s advisory jurisdiction now seems accepted into legal terms: ITLOS’s advisory jurisdiction now appears firmly established as subsequent practice within the meaning of Article 31(3)(b) of VCLT. What began as a bold step, the Tribunal asserting advisory jurisdiction in its Rules despite the absence of any explicit reference in UNCLOS, and then exercising it in 2015 amid fierce criticism, now seems to have culminated in success. A decade on, ITLOS appears to have won a hard-fought battle for its advisory jurisdiction.

Saba Ishkhnelidze is a student in the Erasmus Mundus Joint Master in International Law of Global Security, Peace and Development. His interests include public international law, the law of the sea, and legal theory. He has previously interned at ITLOS and served as a research assistant at the University of Glasgow and Radboud University.