Epistemic Apartheid

Israeli Academia, Silencing and the Knowledge of the Palestinian Other

Silence! Voices must not infiltrate the rhythmic sounds of war, death, and starvation / yet speak, as loudly as you can! Where your words sync with our massacres, when your unequivocal calls are responded to by the cleansing of your enemies.

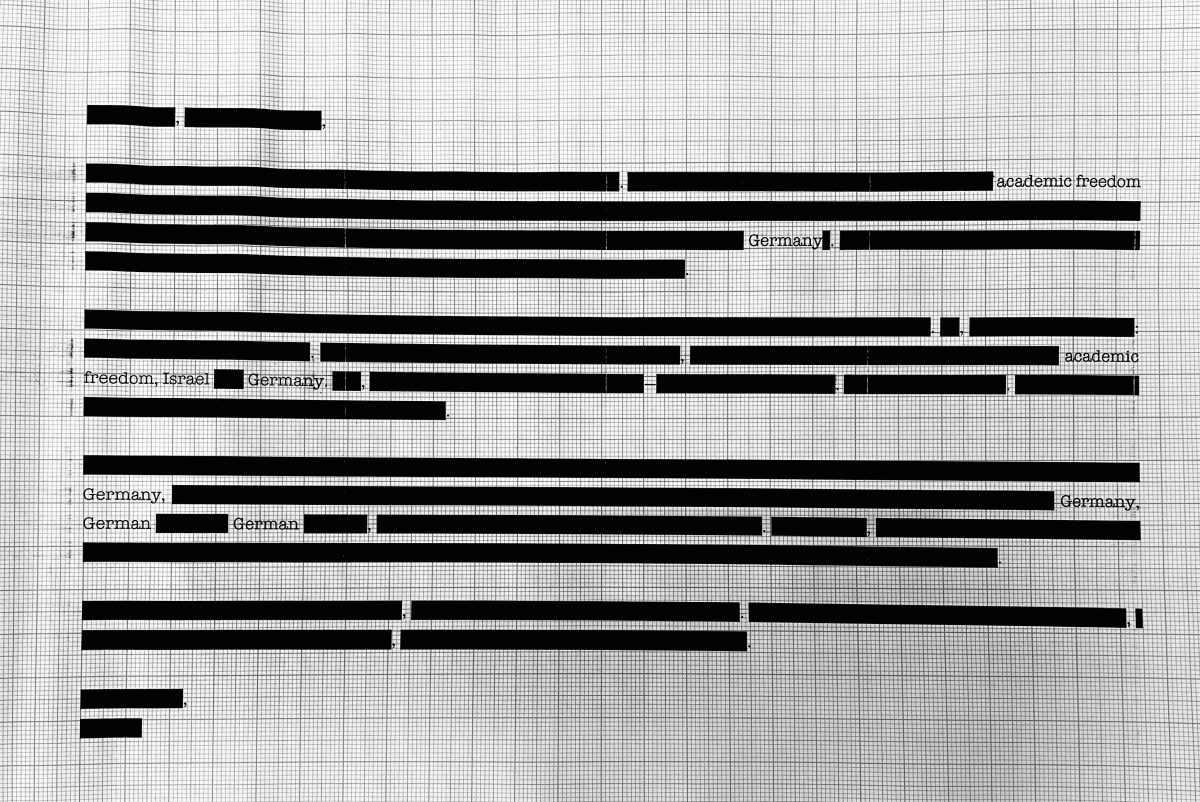

Following the 7th of October 2023, and as Israel launched a genocide war on Gaza, a revenge-fueled crackdown against Palestinian Citizens of Israel and residents of the Occupied Palestinian Territories was initiated by the Israeli Police, Military, and security apparatus. Within months, hundreds of people were arrested in Israel, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem for political expression, predominantly for content posted online. Detainees were blindfolded, harassed, and thrown in security prisons. Some for weeks, others for months (here, here, and here).

As part of this wave of suppression, 34 Israeli academic institutions initiated over 150 disciplinary procedures against Palestinian students and professors (here), often in response to the content they shared online. According to Adalah Legal Center, which represented in the vast majority of cases, students were brought before academic disciplinary tribunals for a wide range of content, including Quranic quotes, personal celebrations (that happened to coincide with October 7), expressions of sympathy with the people of Gaza, criticism of the Israeli regime and military, references to ongoing war crimes and ethnic cleansing, as well as content directly related to the October 7 attack.

While a variety of content was illegalized, a similar pattern of arbitrariness, dominance, and revenge hovered over the cases. Across the protocols, testimonies, and arguments presented in these hearings, a distinct institutional identity has emerged, alongside an underlying perception of who is entitled to access higher education, participate in academia, and engage in knowledge production. Adalah’s report further illustrates that these procedures disproportionately affect Palestinian women, who constitute 77% of the accused, revealing an intersectional dimension to the crackdown.

These repressive actions reflect a societal and structural act of repression through surveillance and institutional power (here and here). As will be argued, this suppression extends to the exclusion of Palestinians as knowers and producers of knowledge, both within and outside the gates of universities. As such, through disciplinary processes, Israeli academic institutions have reproduced Israeli orders of apartheid, settler-colonialism, and domination, restructuring spaces of knowledge production discriminately, where Palestinians’ experiences and truths are denied, dismissed, and sanctioned under the guise of “national security” and “institutional protection.”

Following existing literature on epistemic injustice, Apartheid in academia, and discursive rights, I will argue that during the recent crackdown, Palestinian students are being discredited and sanctioned for their identity and speech, and thus shielded from sharing their own experiences and knowledge. This, consequently, reproduces speech, one that is conditioned upon testimonial and hermeneutical injustice, where the confinements of epistemic apartheid become defining features of Palestinians’ academic spaces. This could be reflected in both research (namely in humanities) and academics’ speech (in all academic departments, as it reflects the political positions and expressions of academics within and outside of academia), as the “guardians” of academic freedom become the oppressors of political discourse.

This piece will start by contextualizing the recent crackdown within the wider oppressive, exclusionary role of Israeli academic institutions vis-à-vis Palestinians. It will present how such measures institutionalized structures of domination through independent interpretations of Israeli law, exceptionalizing Palestinians within the academic community, and securitizing their speech and existence within campuses. Afterward, the article will focus entirely on how these academic institutions positioned themselves as the “deciders of truth”. To do so, arguments about epistemic domination and apartheid in academia will be presented by two examples from disciplinary proceedings initiated during the current war in Gaza.

Centers of (Which?) Knowledge

The recent crackdown on Palestinian students, researchers, and professors has marked an incline in the severity of repression of their voices, as well as a clear repositioning of their academic institutions. Nevertheless, these measures follow and rely on preexisting patterns of epistemic domination and exclusion embedded within Israeli academia. As leading universities were founded on ethnically cleansed villages (e.g., Tel Aviv University) and stolen Palestinian archives (e.g., the Hebrew University and the subsequent National Library Archives) during the Nakba in 1948, Israeli academic institutions institutionalized domination as a default feature of their knowledge production mechanisms long before the current war; either by benefiting from the ethnic cleansing and exclusion of Palestinians, or by taking an active part in constructing it.

On one hand, these institutions, through various collaborations, produce knowledge for Israel’s security-military apparatus, introducing a militarized academia used for the erosion, occupation, control, and ethnic cleansing of Palestinians, including direct contribution to Israel’s genocide in Gaza (here and here). For example, Tel Aviv University hosts the Institute for National Security Studies, the INSS, in which academics and military personnel work together to develop legal guidance for the Israeli military, government, and policymakers, legitimizing the targeting of civilians throughout Israel’s wars and military operations in Gaza, the West Bank, and other places. In weapons production, the Technion has multiple partnerships with Israel’s top weapons manufacturers, including Elbit Systems.

On the other hand, academic institutions have prevented, halted, and discredited Palestinian scholars for their scholarship and research, through direct censorship and unmarked surveillance mechanisms, as well as punished and disciplined students for their activism and pro-Palestinian stance and blocked student movements’ activity on campuses (here), establishing epistemic domination and apartheid in knowledge production through explicit and implicit means.

Recent disciplinary procedures follow and deepen such structures. By conducting hearings and convicting students for alleged online speech offenses, Israeli academic institutions have established their role in repressing the speech of Palestinian students as Palestinians. They acted beyond the scope of their legal authority, censoring, illegalizing and sanctioning students’ digital expression despite clear limitations in Israeli law, which restrict the application of university disciplinary rules of conduct to actions directly connected to students’ academic activities or behavior on campus. Academic institutions established such authority with the direct support of the Israeli Government and its education minister, as well as societal right-wing mobilization, such as Im Terzu, which called for the expulsion of students and organized campaigns supported by student “ratting” mechanisms (here).

This expansion of disciplinary power has been founded through broad, security-oriented interpretations of the Students’ Rights Law. Under this new framework, Palestinian expressions of dissent, solidarity, or grief have increasingly been framed as existential threats, not only to the academic institutions themselves, but also to Israeli society and the state at large. As such, Palestinian students were systematically constructed as disciplinary-judicial “others,” subjected to exceptional measures and treated as inherent security risks, mirroring broader racialized policing practices rooted in the logics of supremacy and colonial control (following Israel’s policing design of racial supremacy, e.g., here and here).

Academia as “Deciders of Truth”: Examples of Disciplinary Cases

The otherness of Palestinian voices was especially established through Israeli academia’s self-interpreted role as deciders of (il)legal – or (un)speakable – speech. These procedures, often indoctrinating (through defendants) a general wider public (supposedly, the institutions’ academic community, sometimes the wider Israeli public) as to what can and should be said during war, have categorized Palestinian students’ online content as opposing ideological narratives, framing them as anti-Israeli, pro-Palestinian, pro-Gaza, pro-terrorism, etc. These narratives, as war necessitates, must be prohibited, sanctioned, and discouraged.

Various oppressive structures have emerged from these processes, where the definition and legality of culture, language, religion, identity, aesthetics, truth, and more are decided by academic disciplinary tribunals. While a deeper study and analysis into the formulation and effects of these structures on linguistics, self-definition, beliefs, and expression remains important, this section will focus solely on the restructuring of epistemic spaces, by what is described here as the deciders of truth. i.e., where academic institutions define which information, definitions, and knowledge reflect what they perceive as “the truth” – and are thus speakable. This argument will be exemplified by two disciplinary procedures that were initiated during the war on Gaza at Ben-Gurion University and Wizo Academy of Design.

At Ben-Gurion University, a Palestinian student was charged for reposting a video on Instagram that questioned widely circulated and unverified claims, such as the alleged beheading of 40 babies, systematic sexual violence, and the massacre at the Nova Festival. The video framed these narratives as part of a broader strategy of “atrocity propaganda” and an ongoing “war on information,” designed to dehumanize Palestinians and justify acts of mass violence against them.

In the disciplinary charges, the university prosecutor charged the student with “harming the educational fabric” of the university, and severely harming “the feelings of students and faculty members,” constituting a disciplinary violation of “a behavior not befitting a student in university, whether it happened within the university of outside of it…” and “a behavior that harmed or could have harmed, intentionally or negligently, the dignity and/or the reputation of the university or its professors, workers, students or guests.”

The student testified that they shared only the first part of the video, unaware of the remainder, and stated that the intent was to raise awareness about misinformation. Despite providing this context, along with fact-checking sources and investigative reports debunking the claims on beheaded babies, the disciplinary panel discredited the student’s testimony entirely. The prosecution presented no counter-evidence and instead deferred to the university administration’s unchallenged assertion that they simply “know what happened.”

Judges further questioned the student on whether posting the video was “right,” and how much they regretted it, particularly in light of classmates who had lost loved ones in the October 7 attacks. The prosecution even brought a fellow student from the same cohort, neither a victim of the disciplinary violation nor an expert, as a witness. The judge asked the witness whether the video constituted support for terrorism, to which they replied “yes.” They were also asked whether the video caused harm, prompting a response detailing emotional and collective trauma experienced by students and faculty. These proceedings raise serious concerns about the integrity of the rule of law within university settings. The heavy reliance on emotional appeals, subjective interpretations, and institutional presumptions, rather than objective evidence, evokes troubling parallels to a Schauprozess, a show trial, where the outcome appears predetermined and due process is sidelined.

Similarly, at the WIZO Academy of Design and Education (which merged into the University of Haifa), another Palestinian student faced disciplinary charges after posting two stories on Instagram, one of them of a picture of the fence surrounding Gaza being broken on the 7th of October and people entering through it, with the caption “while the ‘army that is not defeated’ was asleep,” and the second a story about the massacre at Al-Ma’amadani (Al-Ahli) Hospital, which killed 471 and injured over 300. Regarding the first, the student stated that she intended to share a news snippet about the events. As for the second, the student testified that she had intended to raise awareness about the atrocity, yet was accused of spreading false information and supporting terrorism. During the hearing, the disciplinary panel questioned whether the student truly understood what a “massacre” was, accusing her of echoing “Hamas propaganda”. The final decision declared that using the term “massacre” to describe Palestinian suffering was illegitimate, asserting that “unfortunately, a massacre is what was done to the citizens of the State of Israel and not to the Palestinians”. The committee’s framing rendered the term “massacre” exclusive to Israeli victims, thereby erasing the suffering of Palestinians and criminalizing any attempt to narrate it. Eventually, she was convicted of “behavior not befitting a student, whether inside the academic institution or outside of it,” and was sentenced to one year of suspension.

In her book Epistemic Injustice: Power and Ethics of Knowing, Miranda Fricker discusses two types of epistemic injustices: testimonial injustice and hermeneutical injustice. Testimonial injustice is a kind of epistemic injustice that occurs when someone is wronged specifically in their capacity as a knower. The central systematic case of such is characterized by “identity-prejudicial credibility deficit,” when a shared imaginative social identity leads to an act of injustice, giving less credibility to the speaker due to systematic prejudice of their identity. Hermeneutical injustice, on the other hand, occurs when “some significant area of one’s social experience [is] obscured from collective understanding owing to a structural identity prejudice in the collective hermeneutical resource”.

In both cases, the students were subjected to epistemic injustice. Their Palestinian identity became central to the disciplinary proceedings, not as background context, but as the very grounds on which their credibility was denied. Their testimonies were discredited not on the basis of factual inaccuracies, but because of who they were and the political implications of what they dared to say. The ability to report on what the student perceived as Israeli propaganda and distribution of information, or even to refer to events like the Al-Ma’amadani Hospital bombing as a “massacre,” was systematically delegitimized. In contrast, the prosecution witnesses, regardless of their lack of direct involvement or expertise, were granted the authority to define what constitutes “terrorism,” “truth,” and “harm”.

These disciplinary procedures reflect not only a crackdown on speech, but a deeper restructuring of academic spaces, turning institutions of higher learning into instruments of epistemic policing. Testimonial injustice, as such, becomes epistemic violence, when the university itself transforms from a space of knowledge production into one of surveillance, punishment, and ideological enforcement, thereby casting Palestinians in a permanent role of subalterns. As a consequence, the right to narrate, contextualize, or even feel one’s own suffering becomes conditional, reserved only for those whose perspectives align with dominant Zionist narratives.

This phenomenon is not isolated. According to Adalah Legal Center’s report mentioned above, there is a clear motif of racist viewpoints that attribute charges of “support for terrorism” solely based on the identity of the publishers, assuming that every Arab Student is a “terrorist supporter”– a physical and epistemic threat, unless proven otherwise. As such, these hearings follow common patterns: speech is framed as a security threat, Palestinian students are portrayed as disruptive or dangerous presences on campus, and expulsion or suspension is a frequent outcome. The disciplinary system effectively treats their very presence as a form of danger or incitement, necessitating removal.

These disciplinary procedures constitute a form of hermeneutical injustice as well, where the conceptual resources needed to describe and understand Palestinian experience are systematically denied. When even the word “massacre” is censored, the possibility of developing a future epistemic account of Israeli violations of international law, including unprecedented war crimes amounting to genocide in Gaza (here, here, here, and here), is foreclosed. The ability to describe reality is stripped away, rendering Palestinians not only politically but also epistemically invisible.

As Judith Butler has argued in Implicit Censorship and Discursive Agency, censorship does not merely block speech; it produces speech, shaping discursive possibilities in advance by determining what can be said, by whom, and how. This implicit censorship becomes embodied within the very conditions of academic participation, imposing what could be called a “Palestinian conditionality” on access to education, where the cost of remaining within the academic community is self-censorship, disidentification, and silence.

What emerges from this environment is what scholars Bernal and Villalpando describe as an Apartheid of Knowledge, a system of epistemological racism that delegitimizes entire modes of knowing. In Israeli academia, this is manifest in the criminalization of Palestinian perspectives, the exclusion of Palestinian narratives, and the institutionalization of unequal discursive rights. Academic institutions do not simply reflect broader political conditions; they actively reproduce them. Through disciplinary mechanisms, they participate in settler-colonial and apartheid structures, reinforcing the idea that only certain lives, experiences, and truths are speakable. In this context, the struggle for Palestinian academic freedom is not just about access to education—it is about the right to think, speak, and be recognized as a knower. It is about facing a regime that polices not only borders and bodies, but also language, memory, and meaning.

Conclusion

These recent repressive measures reflect a socio-legal control structure that dominates and subjugates the epistemological possibilities of Palestinian students and scholars, but also extends to their mere existence in public and private spaces, as knowers, producers of knowledge, and most notably, as Palestinians.

As opposed to existing limitations on Palestinian scholarship, disciplinary procedures described above establish legal-structural limitations on the mere access to academia, redefining what a “student” is, and instituting racialized walls that are visible to Palestinians only.

Israel’s attack on Palestinian academia, through the sanctioning of speech, the prevention of Palestinian scholarship within Israeli universities, the isolation and control of Palestinian Universities in the West Bank, or the complete erasure and destruction of universities in Gaza (described as epistemicide or scholasticide) reflects a general notion of racial supremacy within the Israeli legal, political, and academic systems. In these systems, the production and seeking of knowledge are entrenched in colonial domination, as the exclusion of Palestinians becomes a defining epistemological feature.

Disclaimer: The author was involved in one of the cases mentioned in this blogpost in his capacity as a lawyer at the Adalah Legal Center. He has received permission to share the experiences described in this blogpost.

Adi Mansour is a PhD researcher at the European University Institute. His research focuses on the weaponizing of digital infrastructures and the emergence of visible and invisible surveillance and control structures regulating Palestinians’ and Kurds’ online content. He is also a lawyer at Adalah Legal Center, where he works in the Political and Civil Rights Department.