A Question of Authority and Risk

Should the ICRC Publish a New Edition of Its Customary International Humanitarian Law Study?

Editor’s Note: This post is part of a symposium relating to the ICRC’s customary international humanitarian law study, featured across Articles of War and Völkerrechtsblog. The introductory post is available here. The symposium highlights presentations delivered at the young researchers’ workshop, Customary IHL: Revisiting the ICRC’s Study at 20, hosted by the Institute for International Peace and Security Law (University of Cologne) and the Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict (Ruhr University Bochum) on September 18-19, 2025.

The International Committee of the Red Cross’ (ICRC) Customary International Humanitarian Law Study (the Study) has shaped the practice and discourse of international humanitarian law (IHL) for two decades, as it provided the first comprehensive attempt to map out customary IHL across both international and non-international armed conflicts. It is widely cited in courtrooms, relied upon by States and international organizations, and has become a standard reference for scholars and practitioners alike (see here and here), underscoring that it enjoys a high degree of factual authority. It is precisely because of this authority that the idea of publishing a new edition raises difficult questions. Would a revision strengthen IHL’s relevance in light of new practice and technological change, or would it risk undermining the authority that the Study has carefully built since 2005? This blog post argues that, at least for the time being, the latter danger outweighs the potential benefits and that any decision to revise the Study must therefore be approached with great caution.

The Authority of the 2005 Study

As I have argued elsewhere, the authority of the Study can be traced to four distinct marks of authority: (1.) the expertise of its authors, (2.) the institutional authority of the ICRC, (3.) the underlying drafting process, and (4.) its form. In addition, (5.) its methodology, and (6.) the tradition of reliance that has emerged around it, have further contributed to its authority.

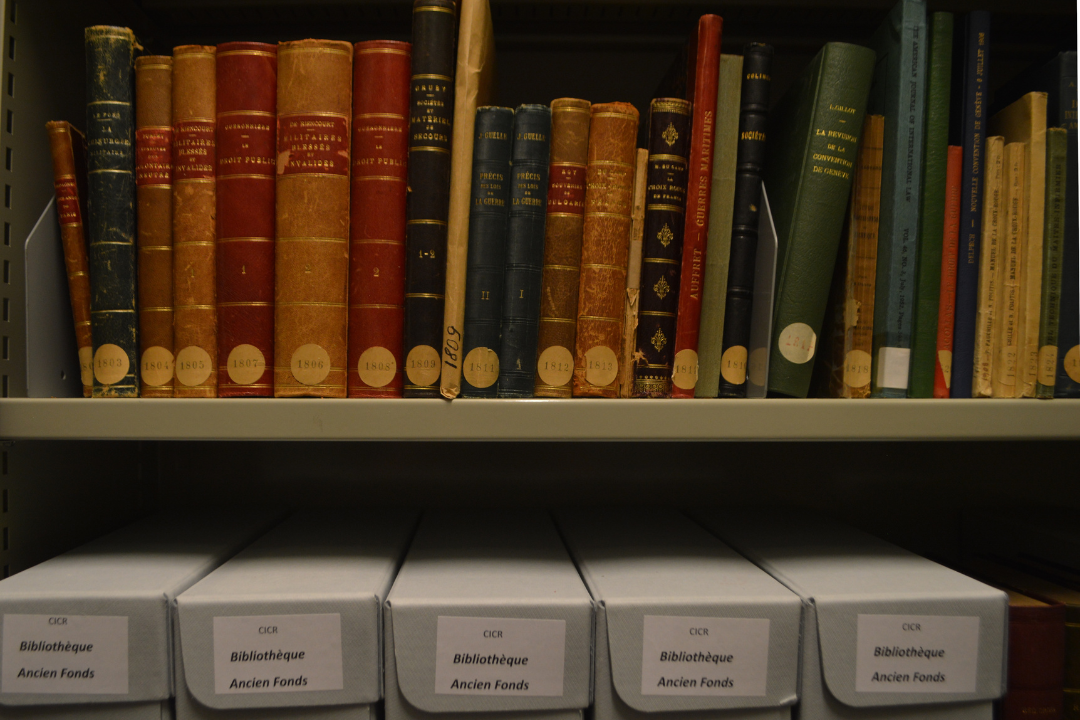

- The Study was the product of a ten-year research process carried out by a team of highly qualified scholars and practitioners. Among them were (former) judges at international courts and tribunals and (former) members of the International Law Commission (ILC). In total, over 100 experts were engaged in the preparation of the Study. This wealth of expertise was unique, not least because it drew on ICRC archives that are not publicly accessible. The Study’s expertise was also underlined by its publication with Cambridge University Press, renowned for its academic standards.

- The ICRC’s institutional authority especially stems from its perception as a unique actor and as guardian and promoter of IHL. Its long-standing role as the institution behind the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocols and the Commentaries thereon reinforced the perception that the ICRC had the necessary experience to identify rules of customary IHL. On this basis, at the 26th International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, the ICRC was given a mandate in accordance with Article 5 (h) of the Statutes of the Movement to prepare a report on the status of customary IHL.

- The underlying process of the Study was carefully designed and rarely the subject of criticism. A Steering Committee of twelve renowned experts elaborated the plan of action and guided the process. Thirty-six academic and governmental experts from all regions of the world were consulted in discussions on a preliminary assessment and later provided comments on two drafts. Forty-seven national research teams, selected for their geographical representativeness and experience with armed conflicts, collected sources of national practice, while six teams compiled practice from international sources.

- The title of the Study’s first volume, “Rules”, and the formulation of the 161 rules in black letters imply that the Rules are definite. The wording of the Rules is very clear and coherent, and the Rules are distinguished from the commentary. In this way, the Study resembles an official codified text containing binding rules. In fact, the Rules have often been referred to as comparable to treaty rules in academia and legal practice. Moreover, the Study is widely accessible and easy to use. It gives non-specialists access to customary IHL. Before the release of the Study, customary IHL rules were known to only specialists, who discussed their formation, method of identification and formulation among themselves.

- The methodology of the Study was, from the outset, a frequent target of criticism (see e.g. here and here). States and scholars questioned, for instance, the sources of practice used by the Study for the identification of customary IHL (see e.g. here and here). Yet over time, such debates did not erode the Study’s authority. On the contrary, the methodology developed by the ICRC was subsequently used in legal practice and academia (see e.g. here and here). Its practical utility, combined with continued reliance in jurisprudence and practice, ensured that methodological controversies did not diminish the long-term authority of the Study. It arguably even influenced the ILC’s later work on the identification of customary international law (see here).

- Over the past two decades, a tradition has developed of relying on the Study and the ICRC’s online database that records state practice as standard reference points. The database is accessed millions of times each year, underscoring its high relevance in academia and practice.

Risks and Challenges of a New Edition Today

Authority is never fixed; it depends on context. The environment in which a new edition would be received is vastly different from that of 2005. International relations are more polarized, and skepticism toward international institutions and international law in general has grown. A revised Study would face not only the scrutiny of scholars but probably also the pushback of States that perceive any limitation on their conduct of hostilities as unacceptable – especially if it comes from NGOs like the ICRC. Several interrelated risks deserve careful consideration.

1. Renewed Criticism from States

At the time of its publication, the Study provoked sharp criticism from States directly involved in conflicts (see here and here). A new edition would likely face similar reactions – if not stronger ones – given today’s heightened geopolitical tensions. States are more sensitive than ever to attempts to restrict their conduct of hostilities. Particularly sensitive are those rules that States have only hesitantly come to accept as customary, e.g. Rule 6, including the qualifying phrase “and for such time as”. Reopening these debates might invite States to challenge even long-settled norms, thereby weakening rather than strengthening their acceptance.

In addition, since 2005, many new State practices have emerged, in some cases pointing in directions that may conflict with the rules as originally identified. A new edition would give those States and scholars who have already contested certain rules a new opportunity to point to recent practice in order to question them.

In general, governments might – depending on the extent and content of new rules – perceive a renewed Study less as a restatement of existing law and more as an attempt to impose new limitations.

2. New Rules and the Risk of Contestation

Any attempt to add or reformulate rules would immediately provoke controversy. Sensitive issues such as the prohibition of the use of nuclear weapons or of landmines illustrate this difficulty (in his contribution to the symposium, Stanislau Lashkevich discusses the examples of reprisals against civilians and environmental protection). These rules are often assumed to form part of customary IHL (see e.g. here and here), yet their precise scope and the way they are applied remain hotly contested. A revised Study could not avoid taking a position on such debates, and in doing so would inevitably reopen disputes that might weaken its authority.

3. Methodological Constraints

At the time the Study was prepared and published, a debate on customary international law was in full progress. Various approaches to identifying customary international law were discussed in academia. In the case law of the ICJ, different approaches to customary international law were observed. The Study was primarily based on the approach of the International Law Association in 2000, which at that time, was the first comprehensive inquiry on the identification of customary international law. Since then, the ILC has adopted a set of draft conclusions for the identification of customary international law. Given the authority of the ILC, they are expected to become the standard point of reference (c.f. also here and here). While these standards arguably confirm the ICRC’s earlier approach (see here and here), any new edition would be judged against them. If the ICRC were perceived to deviate, it would risk being accused of methodological inconsistency (c.f. also Tom Gal’s and Paulina Rob’s contributions to the symposium).

4. Evolving Discourses and the Need for Inclusivity

In 2005, the Study was essentially an IHL project led by IHL (or LOAC) lawyers. Today, debates about IHL involve specialists from many other fields of international law, such as ICL, IHRL, or even international investment law. While broader participation can enrich debate, it also makes consensus harder. The Interpretive Guidance on Direct Participation in Hostilities is a telling example: the attempt to include many perspectives exposed disagreements that could not be resolved, and the contested process damaged the authority of the Guidance (for a detailed discussion of the Guidance’s authority, see here). A new edition of the Study would require an inclusive process, which would be both demanding in terms of resources and accompanied by complex sensitivities in balancing different perspectives.

5. The Changing Nature of Warfare

Technological changes in warfare – most notably the use of drones and the emergence of artificial intelligence – pose undeniable challenges for IHL. Yet the core rules identified in the 2005 Study remain applicable (see e.g. here and here; but see also here). They are formulated in sufficiently general terms to cover new means and methods of warfare. What may be needed are updated commentaries and examples of State practice, not new rules. Attempting to revise the Study to accommodate every technological change would risk diluting the clarity and simplicity that give customary rules their strength. The ICRC’s online database already performs this function: it records new practice without altering Volume One of the Study, which includes the black-letter rules. A revised commentary on the rules, however, would amount to a new publication of Volume One and could open the door to renewed criticism of the entire Study.

Conclusion: Authority at Risk

The 2005 Study has become an indispensable reference point in IHL. Its authority rests not on legal bindingness but on factual authority, especially based on the expertise, the institutional authority of the ICRC, the underlying process, and the Study’s form. A new edition could trigger intense criticism, invite states to challenge even long-accepted rules, and burden the ICRC with politically charged controversies. Such criticism could also endanger the authority of the new Commentaries and of IHL more generally.

For now, the risks of a new edition far outweigh the potential benefits. The authority of the Study is a precious asset that should not be jeopardized lightly. Instead, the ICRC should continue to pursue the path it has taken over the past two decades: issuing thematic studies on emerging issues, providing updated commentaries on the 1949 Geneva Conventions (see here, here and here) and the 1977 Additional Protocols, and maintaining the online database. This incremental approach allows the Study to remain relevant without reopening its substantive foundations. Yet, sooner or later, an update of the Study will become necessary – especially if it becomes evident that several rules no longer reflect customary law or that important rules are missing. But the current situation speaks against such a step. In particular, the completion of the ongoing Commentary project should be awaited first, as the Commentaries on the Fourth Geneva Convention and on the Additional Protocols are likely to generate more controversy than those on the First to Third Geneva Conventions. Only after this experience will it be possible to assess how a new edition of the Study might be received.

The enduring strength of the Study lies in its simplicity and the consensus it has generated. Preserving that legacy is more important than attempting to reinvent it. On its twentieth anniversary, the wisest course is not to replace the Study, but to safeguard its authority for the decades to come – including for potential court proceedings concerning war crimes committed today.